Although the acronym SLAPPs (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation) emerged in the United States in 1996 from Professors George Pring and Penelope Canan’s ‘SLAPPs: Getting Sued for Speaking Out’, it originated with Sir James Goldsmith, Robert Maxwell and Mohamed Fayed in their attempts to silence their critics. Drugs companies such as Upjohn and the Sacklers’ Purdue Pharma and corporations such as McDonald’s and Nomura followed suit. Notorious fraudsters have used SLAPPs, as have politicians, convicts and sexual abusers.

They bring not just libel, but also data protection and privacy claims. Court actions are the tip of the iceberg. In 2014, Cambridge University Press felt unable to publish Professor Karen Dawisha’s book ‘Putin’s Kleptocracy’ because of libel threats. In 2020, Catherine Belton’s book ‘Putin’s People’ resulted in a raft of unmeritorious claims by oligarchs and an oil company keen to please Putin after Alexei Navalny praised it.

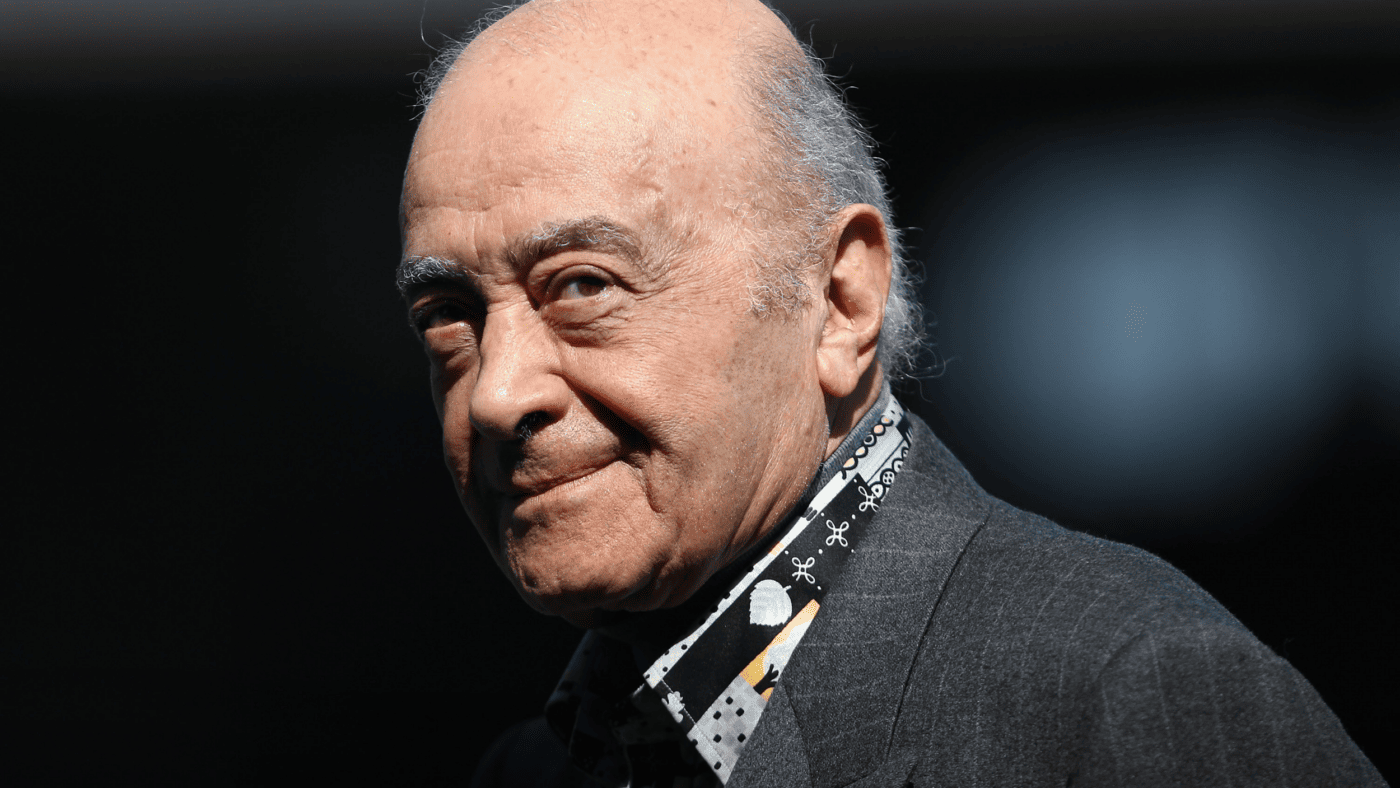

Despite the evidence of sexual abuse, intimidation, bugging, racism and corruption of the police that Vanity Fair uncovered to defeat Fayed’s libel action in 1997, Fayed managed to restrict media reporting during his lifetime. The media either did not publish or they self-censored.

The UK is the destination of choice for SLAPPsters and reputation launderers. The burden of proof is on the publisher and it can cost millions.

Not only have Russians, often with prison records, as well as Ukrainians, Kazakhs, Azerbaijanis, Swedes, Greeks, Germans, Maltese and Chinese brought or threatened SLAPP claims in this country, but England has exported its libel expertise. As the Foreign Policy Centre reported, the UK ‘is by far the most frequent international country of origin for such legal threats’. When Daphne Caruana Galizia was murdered in Malta in 2017, she faced 42 libel and 5 criminal libel claims, often from English solicitors.

SLAPPs enable the wealthy and powerful to suppress criticism. SLAPPsters may seek – with a melee of win-at-all-costs lawyers, private investigators, hackers or PR men – to silence their opponents, rather than pursuing a real remedy.

Some 33 US states have anti-SLAPPs laws. In April 2024 the EU passed an anti-SLAPPs directive requiring implementation within two years and the Council of Europe (46 states and 675 million people) adopted recommendations for setting minimum standards and a regime for tackling SLAPPs. Canada has in place the most effective anti-SLAPPs laws, and has recently published statistics about their operation.

The UK is lagging behind. An anti-SLAPPs law was belatedly shoehorned into the Economic Crimes and Corporate Transparency Act 2023, but restricted to economic crimes. The definition of economic crimes and SLAPPs have the hallmarks of a legal beanfeast. Wayne David introduced a private member’s bill to remedy these defects, but it foundered with the July 2024 election.

There was no anti-SLAPPs act in the King’s Speech. Although Keir Starmer says Labour will introduce anti-SLAPPs legislation, in November 2024 Heidi Alexander MP, then Minister of State at the MoJ, indicated it was not a priority. The government wished to review the operation of the new civil procedure rules enabling SLAPP claims to be dismissed and to await the report of a SLAPPs subcommittee in early 2025. The House of Lords Communications and Digital Committee complained in its Future of News report: ‘the absence of political will to deal with this issue reflects poorly on the government’s values and commitments to justice’. The committee felt such a law should be prioritised and that the Solicitors Regulatory Authority’s fining limit of £25,000 was ‘a peashooter against a tank’. They wanted solicitors not only held accountable for the actions of private investigators and PR consultants they hired, but also to inquire more closely into their clients’ background and the source of their funds. In early February, the Government declined to change its position.

There needs to be a fundamental reassessment of SLAPPs. We should learn from mainland Europe how libel claims are dealt with swiftly and at a minute fraction of the cost here. The public interest defence in libel claims should be reviewed. It all too often focuses on the quality of the journalism. Rather a balance should be struck – as happens in Canada – between the public interest in the freedom of speech and the right to information against the claimant’s need to bring a libel action The excessive cost of libel actions favours the wealthy but excludes the less well-off. The courts’ cost-capping powers should be exercised more fiercely. Much of the problem derives from the technical procedural applications, which can take over a year and cost hundreds of thousands of pounds. There should be early and robust assessments of cases as to whether they proceed to court or whether there are alternative means of resolving them. Too often, courts allow weak but technically arguable cases to proceed to court.

The paperback of David Hooper’s book ‘Buying Silence. How Oligarchs, Corporations and Plutocrats Use the Law to Gag their Critics’ is published by Biteback on 20 March.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.