What connects Martin Luther King and Milton Friedman? George McGovern and Friedrich Hayek? The Adam Smith Institute and John McDonnell?

The answer is that all are fans of the universal basic income – a policy that is suddenly the hottest thing in town. Finland is trying it. Scotland may follow suit. Silicon Valley bigwigs, including Marc Andreesen, are keen. Long explorations of the idea have been published in the Financial Times and New Yorker. And this weekend, Benoît Hamon romped to victory in the French socialist primaries by making it the centrepiece of his manifesto.

Universal basic income – or “UBI”, as the cognoscenti call it – is, in theory, wonderfully appealing. The idea is that rather than doling out benefits, the state guarantees every citizen a certain lump sum per year, handed out regardless of age or need.

You can tweak the model in a host of different ways – by giving higher amounts to the disabled, or the elderly, or smaller amounts to children, or by withdrawing the payment as earnings increase (which is how UBI’s sibling, the negative income tax, works). But the essence is that everyone gets the bare minimum needed to get by.

This has numerous theoretical advantages.

For those who are at the bottom of the heap, it ends the uncertainty surrounding welfare and benefits – they know they will always have just about enough to live on, helping them escape from the poverty trap. (This is similar to the use of direct cash transfers in aid, which have been proven to be far more effective than traditional donations.)

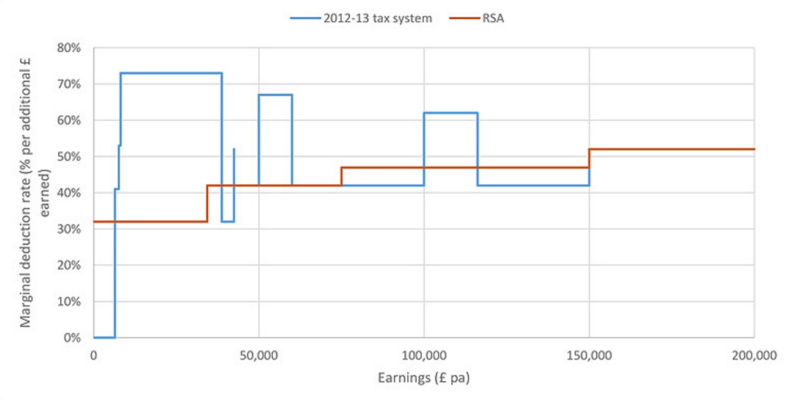

It is also more rational. According to this chart produced by the Royal Society of Arts (which has been one of the biggest boosters of the idea), a British version would drastically simplify the existing switchback ride of tax incentives, while providing a helping hand to the poorest in society.

It is far, far cheaper to administer than the existing system, in which people earn money, then hand it to the government, which hands it back to them. At a stroke, it therefore abolishes much of the bureaucracy associated with the welfare state.

It is also more efficient, and to libertarians, more moral. Giving people money to spend as they wish means that they are more likely to spend it on things they actually need or want, rather than on what government thinks they do. This is one reason why free-market thinkers such as Hayek and Friedman have been attracted to the idea, or variants upon it.

For family-values conservatives, it’s also a good thing because it pays money to individuals rather than households – meaning that couples are no longer penalised for getting together. In fact, most UBI designs in the UK see couples benefiting hugely and single people losing out.

The other main advantages of the UBI are more philosophical – or theoretical. For Anthony Painter of the RSA, and other romantics, it provides people with space to create, to be their best selves, free from the pressures of wage slavery. And the fact that it gives to the rich as well as the poor is, to some, a feature rather than a bug, as it gives them an investment in the welfare state.

Most recently, its benefits have been couched in technological terms, as a hedge against the imminent robot revolution – a way to ensure that those who are thrown out of work by automation and algorithms do not rot on the dole. Some even combine these two Utopian visions, to paint a picture in which the robots do all the boring stuff while we live a life of leisure, using our stipend from the state to support ourselves while we dabble in poetry or pottery-making.

But let’s ignore the robots for now, and deal with the reality. Because it’s one in which the idea of a universal basic income makes a great deal less sense.

For starters, UBI simplifies work incentives, but it also undermines them.

It may sound harsh, but the most successful form of welfare policy over the last few decades has been to stop handing it out. The principle behind the Wisconsin welfare reforms of the Clinton era, and the more recent reforms under the Coalition in Britain, was that there should be no excuse not to work if you could. And the result was an employment bonanza – what Fraser Nelson called, in the British context, a “jobs miracle”.

What these reforms showed was that the best form of welfare was work – that getting people on to the employment ladder, no matter how low the rung, was better for them (and for the state) than funding dependency. A guaranteed income is also a guarantee that it’s OK to be idle. Which is why, as David Frum and Jodie T Allen point out, everyone in the US lost interest in the idea in the first place.

Ah, say the advocates of the basic income, but in that case we’d set it low enough as to incentivise work.

But that brings us on to the biggest problem of all. Which is that this thing costs money. Enormous amounts of it.

The RSA’s version of the basic income looks like it just about makes the sums add up. But that’s because it sets it at a level of £3,692 (in 2012-13 prices, excluding housing and disability support). That’s not very much at all – in fact, it’s about a quarter of the national living wage. And even then, there’s a lot of devil in the detail.

Last year, I went to an event on this topic at the Resolution Foundation. Its experts crunched the numbers and found that, under a UBI scheme that pays people the same as they would get under Universal Credit (ie about the RSA level), and throws in universal child tax credit (rather than means-tested, as under the current system), taxes would have to rise. By a lot.

In fact, you would have to abolish the Personal Allowance – the £11,000 tax-free that everyone gets on their earnings. Instead, from the first pound you earned to the £43,001st, you’d pay a combined rate of income tax and National Insurance of around 35-40 per cent, after which the higher rate of tax would kick in as normal.

In other words, to get that £3,692 from the Government, you’d pay thousands of pounds more.

This would mean (and stop me if you don’t follow the logic) that large numbers of people would be paying a much larger amount of tax. In fact, it would represent a transfer of £120 billion of extra taxation into the welfare state – the equivalent of the entire budget of the NHS in England.

Now, you may not want to take that extra money from the rich. You might want to take it from companies, or introduce the idea more gradually. But if you want to move to a guaranteed income, you have to take it from somewhere.

And if you want to move to the level where it can actually support people to lead those kind of leisure-filled, pottery-making lives, you would need a truly gargantuan amount of money – even if you decided that rich people shouldn’t get it after all (which would obviously be politically appealing).

The best argument against UBI was put by Karen Buck, a Labour MP, at that Resolution Foundation meeting.

She was, she said, in favour of more generous welfare spending. But even she had to admit that introducing conditionality into the welfare system – pushing people off welfare into work – had been both effective and politically popular, and that UBI would throw it into reverse. And if you were going to decide to pump tens of billions of pounds into the welfare system, there were much better and more targeted ways of doing it.

A universal basic income, in other words, is a powerful idea because it seems so clear and so simple – a way to reward work, give security and simplify the welfare state, all at the same time.

But there’s a reason that, by and large, it’s those on the Left who are pushing the idea. Because it’s old wine in new bottles – redistributive, Seventies-style taxation under a trendy new branding.

There is nothing so powerful as a bad idea whose time has come. And reluctant as I am to quarrel with Hayek or Friedman, the sad truth is that universal basic income – at least in anything like the forms that are currently being proposed – is a very bad idea indeed.