How much would you pay a doctor if you urgently needed one – e.g., if you were having a heart attack? This is, of course, a trope familiar to anyone who pays attention to doctors striking over pay in the NHS. I am prepared to admit that I would pay a cardiologist rather a lot of money if it were the only way to save my life. If, on the other hand, there were two cardiologists standing by my bed and only one would be paid for saving my life, then competition might come to my rescue. After all, cardiologists need to eat too, and there is no money whatsoever in either letting people die or constantly losing out to your competition.

Let’s also consider that most people don’t need a cardiologist most of the time, and that many of those who do probably never will because – tragically – one of the most common first symptoms of heart disease is death. However, it does take a lot of effort to be allowed to practice, and only a small number of people have the requisite education and intelligence to do it well, so, like many professions, it’s a pretty good job for those prepared to put the work in. By the time you retire, you will have spent most of your career in at least the top 5% of earners. Balancing these factors together, we find that there is a small market for cardiologists, one that is relatively well-paid, but not without limits.

At the other end of the scale, how much would you pay someone to empty your bins every week of your life? Unlike cardiologists, nearly everyone needs a binman nearly all of the time. It’s scarcely more practical for everyone to empty their own bins than it would be for everyone to teach themselves cardiology; imagine the queue for the local tip! It’s not the most pleasant work, it can be physically demanding, requiring work in foul weather, but neither do you require much in the way of education to qualify. As such, you can’t charge too much for your labour as, in theory, you could be quite easily substituted. At the same time, demand for your services is high enough that you and your colleagues have fairly secure employment at a reasonable wage.

Nothing about this should be controversial. It’s simple economics. Yet how is it that the UK is in the situation where access to both cardiologists and binmen is being disrupted on a near-constant basis?

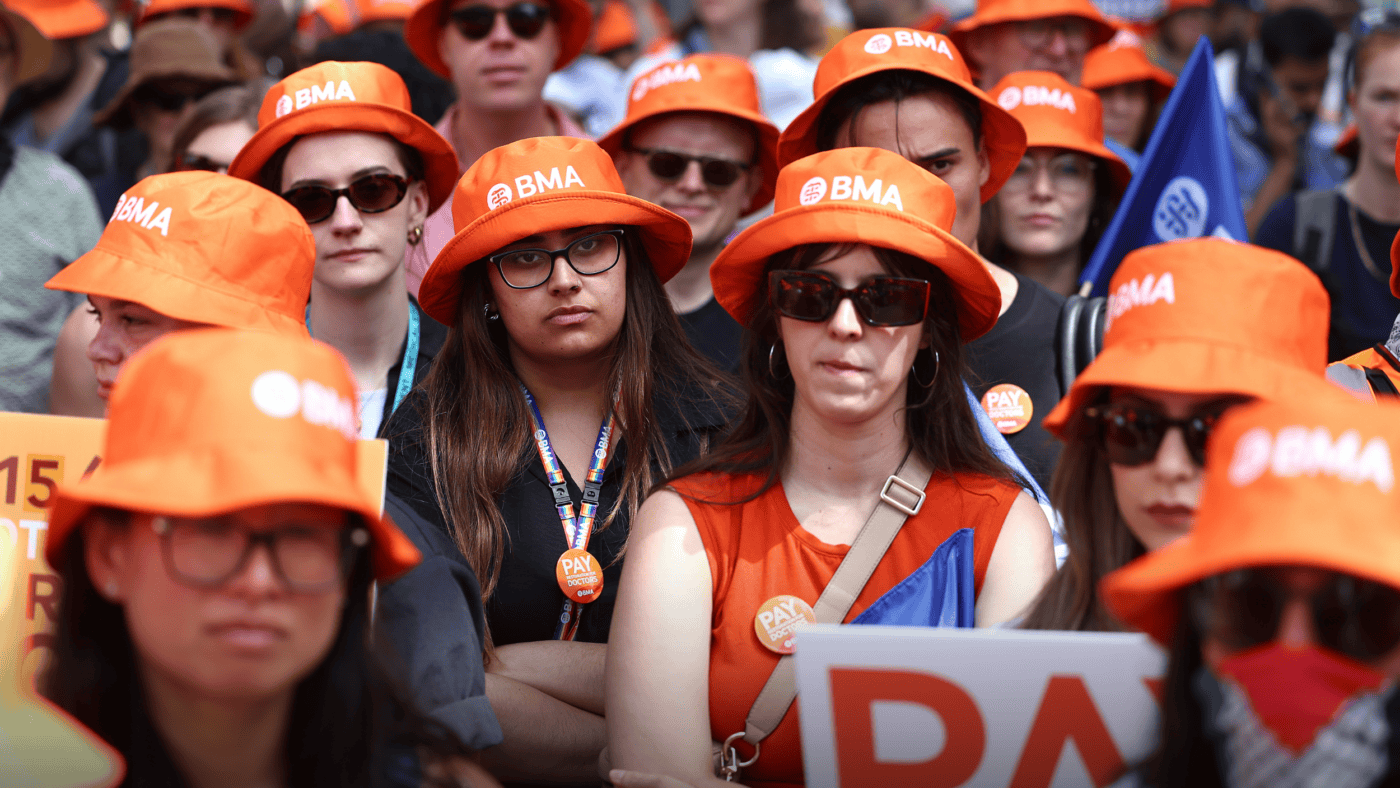

In a stunning display of avarice, the physicians formerly known as junior doctors are seeking a 29% pay rise, having received a mere 22% increase last year, and are threatening nationwide strike action if their claims are denied. Meanwhile, in the UK’s second-largest city, rubbish has been piling up for the last three months over pay disputes, with serious consequences for public health and quality of life. What’s going wrong?

When I was a child, I was given a Mensa puzzle book which contained the following poser: ‘What happens when an irresistible force meets an immovable object?’ The answer was ‘An inconceivable event occurs.’ (No, I didn’t get it.) In essence, the same universe cannot contain both phenomena because they are mutually exclusive. The laws of physics forbid it.

In the UK, we have an analogous question: ‘What happens when a monopoly encounters a monopsony?’ The answer appears to be that no exchange of labour can take place at any price. Such a situation should be inconceivable, forbidden by the laws of economics. To screw things up this badly requires government.

The argument about the wisdom of the NHS operating a virtual monopoly on the provision of healthcare is well rehearsed. And efficiency virtually demands a local monopoly on refuse collection. What is rarely discussed is the role of unions in effectively operating a monopoly (the only seller) of labour while central and local government operate as monopsonies (the only buyers). This has intensified because unions were allowed to merge to create the colossal beasts they are today. Just eight trade unions represent 80% of unionised labour in the UK.

In the private sector, there is an effective feedback loop on union power. If workers demand too much money for their labour – more than the market can bear – then either workers are replaced by technology, jobs are moved to locations with lower labour costs or the companies go bust. The same applies if unions are resistant to reforms of working practices that streamline company operations. Indeed, in the post-war period, the intransigence of British trade unions significantly contributed to the eventual destruction of heavy industry, demonstrating that the feedback loops are real.

In the public sector, no such feedback loop exists. The NHS is not going to go out of business, and neither are councils, schools or state-run railways, because ultimately the government (which is to say the taxpayer) stands behind all of it. The taxpaying public are the ones who pay the price, and so eventually politicians will nearly always cave in to demands from the unions, volunteering the public for higher taxes to pay public servants to do jobs that are often better-paid and have better conditions than those in the private sector. Without the feedback loops that operate in the private sector, there is seemingly no effective brake upon the demands of the doctors, binmen and train drivers. This is nothing short of market failure.

When a market participant becomes over-mighty, governments must act to protect the interests of the consumer. The BMA represents around 90% of resident doctors in the UK and has the ability to bring the primary healthcare provider in the country to a virtual standstill. This is an unjustifiable level of market dominance. But what are the options?

One option is to demand that unions are broken up. Perhaps no union should be permitted to represent more than 20% of workers in an industry. Similar rules governing cartels could also be brought to bear, forbidding such smaller unions from conspiring to take joint action. However, when there is only one employer, and they are working to fixed national pay scales, this still might be ineffective.

The nuclear option would be to extend the ban on strike action from just the armed forces and police to all public sector workers. Given that 96% of strike days occur in the public sector, would workers in the private sector object too strongly? However, it would probably be regarded as an infringement of liberty, and there’s certainly no prospect of a Labour government making such a move, reliant as it is on union funding.

Ultimately, the only solution is more competition. Birmingham council should be actively training binmen to take the place of those in breach of their employment contracts, while the government should be rapidly expanding training places at medical schools and increasing training positions at hospitals. Obviously, it would take some time to filter through, but the direction of travel should be clear. How many cardiologists want to face increased competition for advancement in future?

As long as the government insists on operating its own monopsonies, it needs to be prepared to act against the trade union monopolies. It needs to show it has the heart for the fight.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.