One fascinating theme when looking across the history of politics in general, and of public opinion in particular, is that the great philosophical debates of one era simply don’t crop up in another. Some of the great ideological clashes of the 1970s and 80s around the size of role of the state, for example, became non-issues in the 90s and 2000s.

That could certainly be interpreted as capitalism having won the argument. After all, if even the Labour Party’s then Director of Communications said he was “intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich” it seems reasonable to conclude that, by the time New Labour came to power, the economic system enabling such wealth was accepted by everyone in the mainstream of British politics.

But just because an issue can seem settled at a given moment in British political history, it does not mean that it is settled permanently.

Given Labour’s unexpectedly strong performance in 2017 – in its most left-wing incarnation in decades – it is worth revisiting where the public stands on capitalism.

Polling by Number Cruncher Politics, exclusive to CapX, does just that.

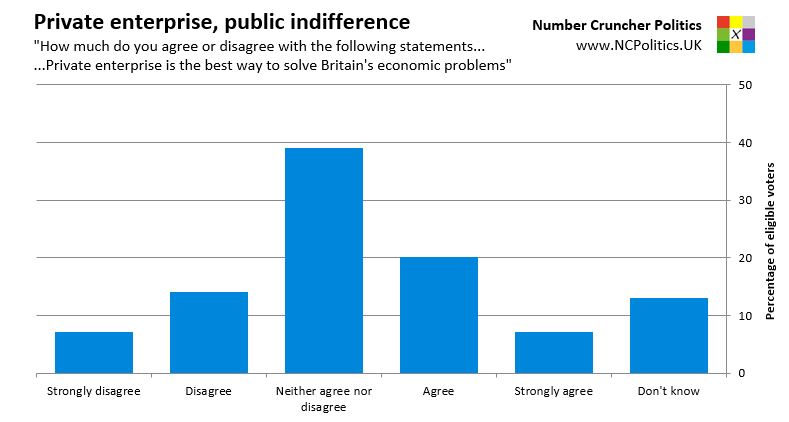

We asked 1,037 eligible voters across the UK for their views. When asked how much they agreed or disagreed with the statement “private enterprise is the best way to solve Britain’s economic problems” we found a 6-point lead for agree (27 per cent) over disagree (21 per cent). But we also found a large plurality (39 per cent) choosing the neutral “neither agree nor disagree” response and a further 13 per cent unsure.

Agreement varied greatly by party, with half – though only half – of current Conservative voters endorsing the statement, but only 19 per cent of Labour voters.

As on many issues, a substantial age gap exists too. Fifteen per cent of 18-24 year olds backed private enterprise, as compared with 36 per cent of over-65s. The latter is coincidentally the proportion across all age groups who agreed when the British Election Study asked the same question in 1992.

How much of that difference is explained by younger people having more general left-leaning sentiments, rather than an aversion to capitalism as a concept? Well, not all of it. Asked about two other statements concerning whether “ordinary working people get their fair share of the nation’s wealth” and whether “there is one law for the rich and one for the poor”, the age gap was much smaller. It seems that although younger generations are not as left-wing as they’re often perceived, free market economics has a brand problem among them.

This might be part of the explanation of why Conservative attacks on Jeremy Corbyn and his policy program failed to stop such large numbers of younger professionals from switching to Labour during the 2017 campaign. That is certainly an area for further work.

It’s also notable just how widespread some seemingly economically left-leaning attitudes are. Sixty-one per cent disagreed with the statement “ordinary working people get their fair share of the nation’s wealth”, while 64 per cent agreed that “there is one law for the rich and one for the poor”. This fits with work from both Britain Thinks and Populus, which found a British public similarly sceptical about the economic status quo.

That, of course, has not stopped the public returning three consecutive Conservative-led governments. The better news for free marketeers is that shared sentiments do not necessarily translate into support at the ballot box – trust and perceived competence matter too.

What should really concern proponents of free market economics the most is public indifference. For decades, mainstream political debate around the economy has been limited to whether markets should be a little bit freer or whether government should intervene a little more, whether regulation should be a slightly more or less laissez-faire, or trade policy moderately more open or closed.

Until recently, the stark difference between a system that’s broadly capitalist and one that isn’t, just hasn’t been discussed very much. And public attitudes reflect this.

In other words, advocates of the market need to win the argument all over again. And do so in a post-crisis world.

Many people – and particularly younger people – don’t have a view on the merits of free enterprise simply because they haven’t thought about it. Capitalism’s advocates need to make the case for their system before someone without dire personal ratings makes the case against it.

That will be easier said than done. Telling people the virtues of your preferred economic system, rather than demonstrating them, seems to work well for those advocating radical change, but is much less straightforward for those advocating something close to the status quo.

That, then, raises the question of how to make capitalism work politically as opposed to just economically. That is the real challenge for believers in the market.