In October 2007, having resigned earlier that year as Prime Minister, Tony Blair gave a speech at Blenheim Palace in which he said:

The real dividing line to think of in modern politics has less to do with traditional positions of right versus left, and more to do today, with what I would call the modern choice, which is open versus closed…

Do we open up? Albeit with rules and controls, or do we hunker down, do we close ourselves off and wait till the danger has passed? Is globalisation a threat or an opportunity?

In many ways, the events convulsing Europe and its institutions – Brexit, CETA and TTIP, the migration crisis – are finding their political form according to this divide.

It is to explore these political and cultural manifestations – populism, Euroscepticism, anti-immigration sentiment and exclusive nationalism – that we at Demos undertook original polling in France, Germany, Poland, Spain, Sweden and Great Britain, as part of a wider project investigating these trends.

A number of interesting stories come out of the results.

First, support for the European project appears remarkably low – even in the traditional motors of the EU, France and Germany. While the data does not show that we are heading for a Frexit any time soon, it does show high levels of support for reducing the powers of the EU across Europe, particularly in France and Sweden.

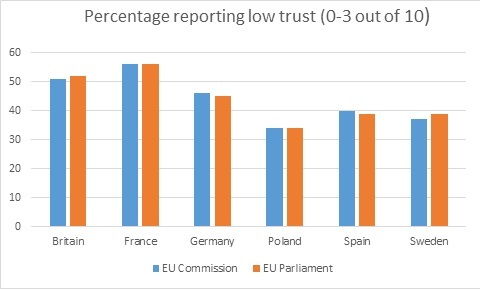

Remarkably, trust in the EU institutionsis even lower in France than in the UK, which as you would expect has very low levels of trust in the Commission and Parliament.

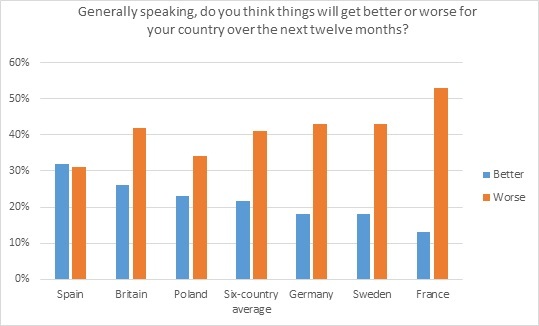

A second important and related finding is that, heading into the Presidential election, the situation in France seems very febrile.

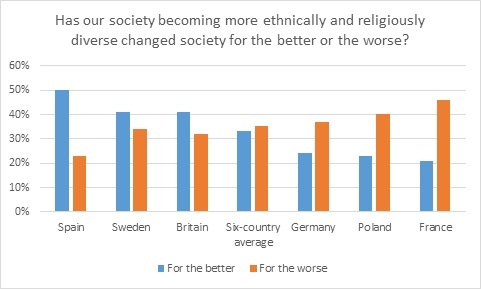

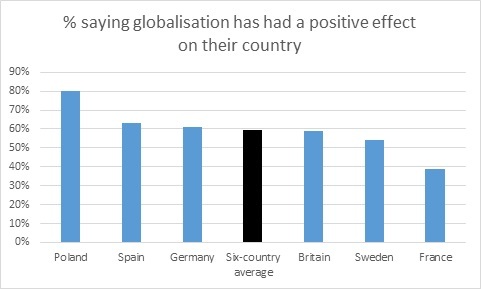

Our French respondents were the most pessimistic about their country’s and their own prospects, most likely to think that globalisation had had a negative effect on them and their country, and most likely to say that they thought ethnic and religious diversity had changed French society for the worse.

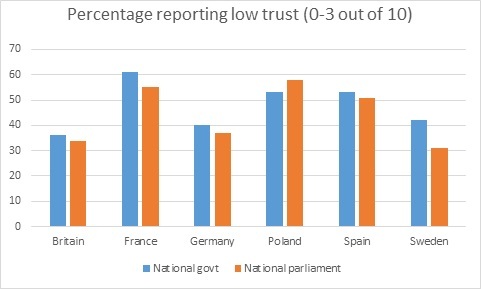

They also are the least trusting of their own political class, indicating that despite the very real issues indicated by our results, they don’t have faith in politicians’ ability to resolve them.

Given the increasingly illiberal tenor of the French election debate, the continuing emergency powers wielded by the executive, and the possibility of Marine Le Pen getting within touching distance of the Presidency, this is perhaps the most troubling finding in our survey.

Third, and I expect of most interest to readers of CapX, is that despite these gloomier findings and recent events, the overall level of support for globalisation across our sample was high.

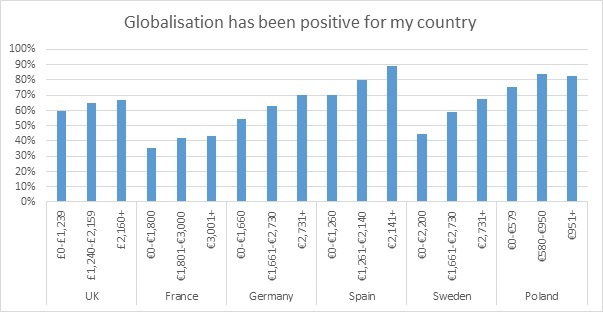

Interestingly, when this is broken down by income bracket, those on higher incomes were more likely to report thinking that globalisation had had a positive effect on their country and on their lives across most of our countries, with the exception of Poland.

This lends weight to the idea that despite globalisation demonstrating majority support in our survey, there are still plenty in Europe who feel “left behind” by globalisation, who perhaps haven’t shared in the economic gains of the past 40 years.

What can be done about this remains an open question – and perhaps the most pressing political question of our times. But we at Demos will be continuing to explore these trends – including an in-depth case study into the underlying drivers of the Brexit vote – as they play out.