Pain, said C.S. Lewis, is bearable if it has a purpose or a deeper meaning. A decade has now passed since the start of the Great Recession, and those who have borne the brunt of it are entitled to ask whether such a purpose lies behind the Western economy’s continuing troubles, and what it might be.

The consequences of economic decline are visible almost everywhere. In many parts of Western society, people are dampening down their expectations about life, income, and well-being.

In countries such as Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States, the dominant opinion is that the next generation is less likely to be richer, safer, or healthier than the last.

For millennials, the job market has become increasingly difficult to navigate, with many having to jump from one low-paid job to the next whilst others can only find poorly paid or unpaid internships. Those who begin their careers out of work are more likely to face lower wages over the course of their working lives along with bouts of unemployment.

Yet not everyone is doing badly.

In the UK, the average income of pensioners is now higher than that of working-age households, once housing costs and family composition are taken into account. Both Western politics and Western economies are increasingly dominated by the needs of grey-haired voters – they are the ones with the houses, with the shares, and the pensions.

Older voters also represent a dominant share of the support for Donald Trump in the US and Front National’s Marine Le Pen in France. If the West’s populist revolt has a colour, it is grey.

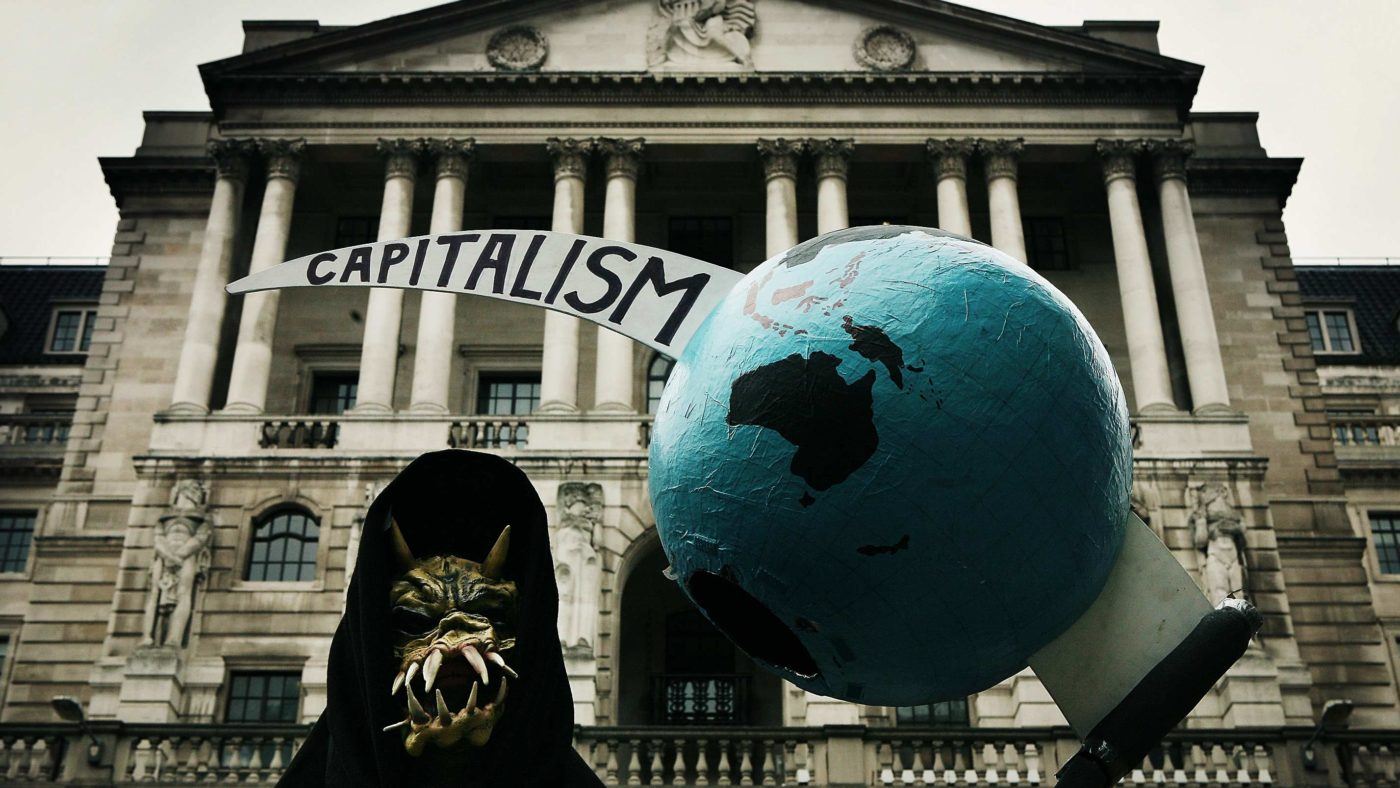

What has gone wrong? Put simply, Western capitalism is not in good health.

For a simple diagnosis, just look at the West’s saturated corporate sector: firms are brimming with cash, but glaringly short of ideas for how to use that excess capital to innovate and grow. Or consider the pace of corporate renewal in Europe. In Germany’s DAX 30 index of leading companies, only two were founded after 1970. In France’s CAC 40 index, there is only one. If you compile a list of Europe’s 100 most valuable companies, none was actually created in the past 40 years.

America is different, but less so than it used to be. Western capitalism has turned into a club with lifetime membership rights, where no one signs out. And where nothing gets destroyed, hardly anything fresh is created.

For new things to grow, as Chance the gardener said in the film Being There, “first, some things must wither”. Withering, as all of us middle-aged people unfortunately know, is never agreeable, but it is a central aspect of the capitalist ecology.

Yes, there has been a flood of money into start-ups. But within larger firms, capitalism is becoming increasingly dull and hidebound.

Four factors in particular are making the economy less prone to innovation: grey capital, corporate managerialism, globalisation, and complex regulation.

What do we mean by “grey capital”? Essentially, this is the idea of capitalism without capitalists.

Leading corporations in America and Europe now have anonymous core or controlling owners, such as investment institutions. And much of this grey ownership effectively invests on the premise that companies should go with the flow of the market rather than beating it.

These owners require corporate managers who steer a steady and predictable course – not entrepreneurs with a habit of economic renewal.

This, in turn, has led to the spread of managerialism. Western capitalism is now a habitat for The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, to reference Sloan Wilson’s book about the boredom of organisation.

Business leaders and grey owners talk about agile adaptation, disruption, and revolutionary innovation when they describe their firms. Yet in reality, corporate managers shy away from uncertainty, turning companies into bureaucratic entities free from entrepreneurial habits. They strive, in other words, to make capitalism predictable.

And globalisation, far from disrupting this tendency, has entrenched it.

The first wave of globalisation – in which manufacturers expanded horizontally into other markets – required some innovation ingenuity, but was primarily defined by the organisation and management of international expansion.

In the second wave – “vertical” globalisation – companies built global production networks based on a high degree of supply- and value-chain fragmentation.

But at the same time, global companies concentrated their focus on their market position, growing defensive about their incumbency advantages and fearful of radical innovation. Barriers to entry went up as market concentration increased and companies accelerated their specialisation, making it more difficult for incumbents to be ousted through innovation.

And just like managers, regulators responded to the increasingly complex world by making regulations more complex. This has led to what political scientist Steven Teles calls a “kludgeocracy” – a patchwork of badly constructed regulations that work with no common organising principle.

The result of all this was that a tendency towards predictability and self-preservation seized the corporate world – edging out economic dynamism and competition.

The chief worry is not that these Four Horsemen of capitalist decline will lower economic growth, but that they will destroy aspiration.

Societies that do not inspire people to imagine the possibility of a better future inevitably decay. They become suspicious of the unknown and embrace politicians who promise to veto change. Economic renewal becomes a threat, not an opportunity.

The good news is that stagnation, like progress, is neither inevitable nor automatic. It is the consequence of choices made by elected officials, corporate leaders, and individuals.

The rise of modern capitalism a quarter of a millennium ago was the result of great political and institutional changes which allowed competition into old economic and societal habits.

And the last quarter-century offers many examples of how people can release themselves from oppressive or taxing economic regimes, and how economies can begin to thrive after decades, if not centuries, of stasis or stagnation. A quarter-century ago, China’s GDP per capita stood at $500; now it is almost eight times higher.

Unquestionably, today’s Western economies can be “fixed”, even if it will take a generation or so to change their culture.

However, that will not happen if the focus is on the standard, off-the-shelf, generic reform programs that economists usually advise.

To spark new life into capitalism, attention must be given to, first, severing the link between grey capital and corporate ownership; second, giving competition a real boost; and third, nurturing a culture of dissent and eccentricity.

Western economies have developed a near-obsession with precautions that simply cannot be married to a culture of experimentation, and the addiction to regulating away various forms of risk has eroded the role of innovation in their economies and effectively neutralized entrepreneurship.

But capitalism did not conquer in the first place just because it raised living standards and gave us products like automobiles, refrigerators, and colour television. Its winning formula was that it made space for eccentric individuals with unconventional ideas.

The deserts of the Siberian tundra, for instance, never had a Burning Man festival like the annual gathering in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert, which draws more than 60,000 techies, entrepreneurs, and others for a celebration of creativity, ingenuity, and self-expression.

An innovation culture requires people who are curious for new knowledge and willing to expose their own ideas to opposition.

Reduce the space for eccentricity and our economies will stagnate. Encourage the same habit – and the world will prosper.

This is an edited extract from The Innovation Illusion: How So Little Is Created by So Many Working So Hard by Frederik Erixon and Bjorn Weigel (Yale University Press)