Who was the greatest Secretary of State for Education? Margaret Thatcher? Kenneth Baker? Rab Butler? Gavin Williamson?

Perhaps, like most people, you have never even considered such a question, any more than you may have contemplated who was the greatest Secretary of State for Health, the Environment, or Overseas Development. Such questions barely get to the end of being asked before indifference muffles any possible responses.

Until now that is. Because this week saw the launch of the Battle of Education Secretaries card game, co-created by former teacher Laura McInerney. For £15 you get 30 cards, each with the name of a former Secretary of State, painted in either lurid blue for Conservative or garish red for Labour. Like Top Trumps, each card has statistics, including dates the minister was in office and an outline of what they achieved (some, like Estelle Morris, are rather thin in this area). Bizarrely, each card also tries to give each politician a ‘likeability’ score out of 10 – Margaret Thatcher is on a rather lowly 3, whereas Tony Crosland is on an 8, which will come as a surprise to anyone who favours academic selection.

It would be easy to dismiss this as some harmless fun for a particularly geeky teacher or policy wonk, but it also neatly encapsulates the infantilism that characterises much of what passes for educational debate around schools in this country. There is something inevitable about teachers creating such a game, and then, a little like the children they teach, tweeting how much they love playing it. One doesn’t have to go too far on social media to find images of teachers happily presenting themselves as figures of ridicule.

Some professions seem too easily and negatively influenced by the people they have to deal with daily: one only has to think of the dissembling and venality of the Metropolitan Police around recent high profile cases to wonder if senior figures have worked too closely, and for too long, with people with rather undesirable moral frameworks. Over time, boundaries can blur. Even our politicians, now discussing the coarsening of public debate, use language which is, at times, indistinguishable from those trolls who hound them online.

If there is a crisis of authority across the West then teachers have played a significant part in creating it. With a frightening willingness to relinquish control, school leaders, teaching unions, and numerous educationalists, openly question the central importance that the adult in the classroom plays in educating children. Witness the predictable ‘progressive’ outrage that follows every (invariably sensible) announcement from the recently-appointed Social Mobility Commissioner – and ‘strictest headteacher in England’ – Katharine Birbalsingh. No matter that Birbalsingh’s school, Michaela, has improved the life chances of thousands of inner-city children, what matters to her detractors, is that she has the temerity to insist on adults – including parents and teachers – taking responsibility for their actions, and act as role models for the children they have a duty of care for.

Boundaries continue to blur in education. Dame Alison Peacock, the chief executive of the Chartered College of Teaching, this week accused Ofsted of conducting a ‘reign of terror’, one which seeks to see teachers reduced to functionaries, a set of ‘robots’ controlled by that scheming pedagogical Pol Pot, the Chief Inspector for Schools, Amanda Spielman.

Whereas in the past sticks and stones alone used to hurt our bones, words too are now capable of inflicting actual physical damage. It is dismaying to see those who could make debate more reserved adding to the heat. Such language is ludicrously overblown, but is recognisably of the playground, characterised by a rapid escalation of accusation and concocted harm, and intended to undermine the legitimacy of those who are doing their essential work in ensuring school standards are maintained and children are kept safe. It is as reductive as it is self-serving, but it is another example of how those involved in schools too often resort to the behaviour of a spoiled teenager unable to get what they want.

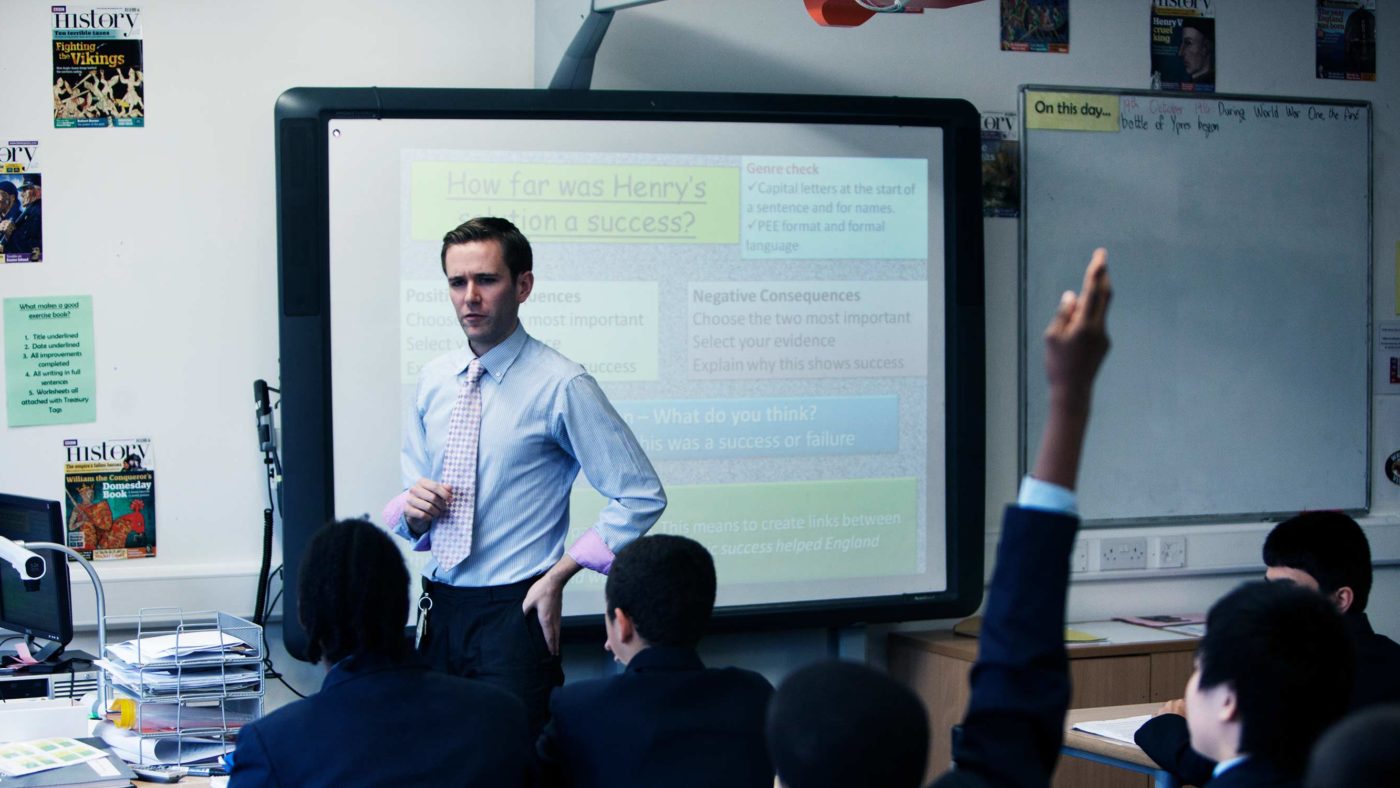

The tragedy for teachers is that there are now very few figures, or organisations, representing them who believe in the central importance of adult authority. Some genuinely seem to believe that, left alone with a computer, children will learn by themselves. But if school standards are to be restored, if the moral and cultural relativism that actively inhibits learning is to be challenged, then we have to put the adults back into the classrooms. The culture wars that threaten to wash away so much that should be valued and cherished, and which our children have a right to know, can only be stopped if schools act as bastions of shared, national identities. Such considerations should trump all others.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.