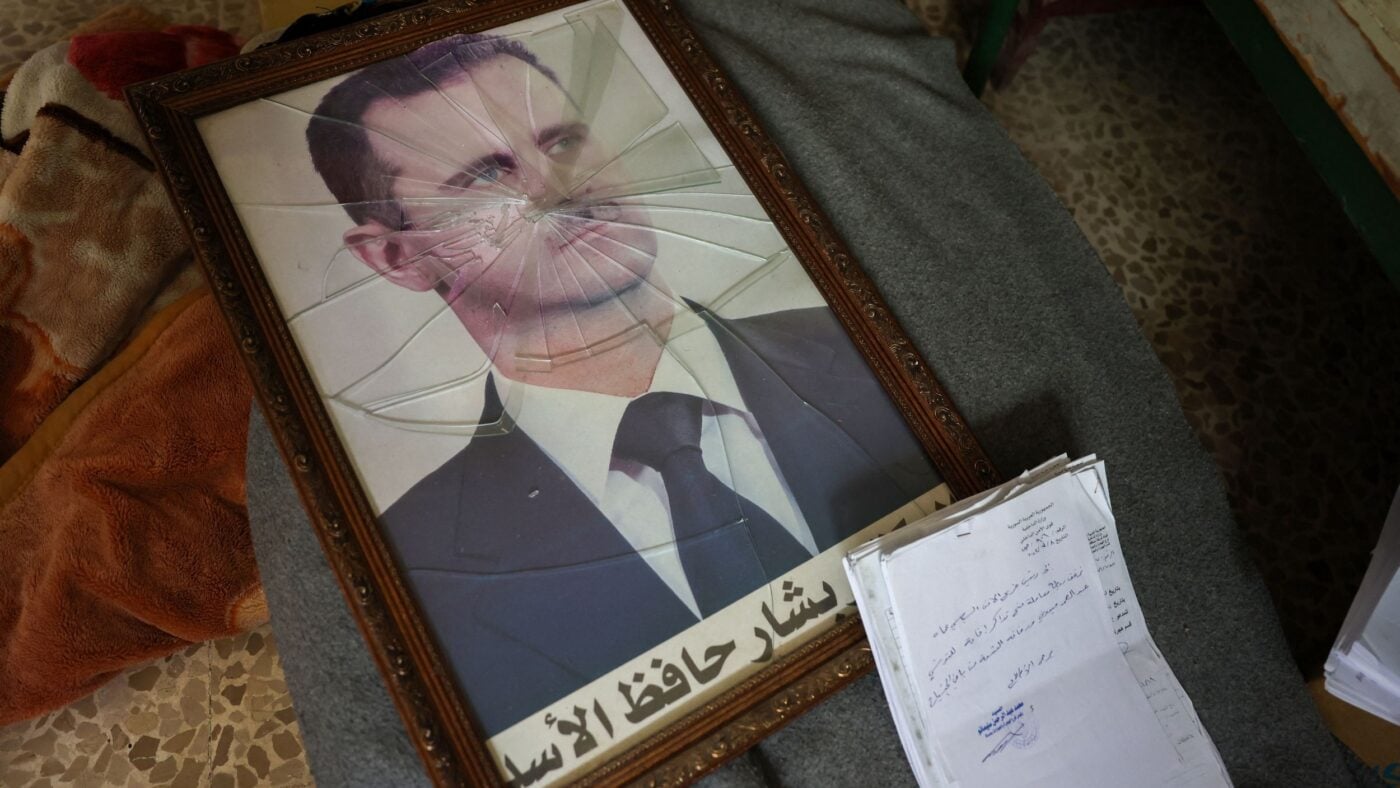

The Islamist-led rebel offensive in Syria has been executed with devastating effect, ending Bashar al-Assad’s lengthy reign as president and five decades of dynastic rule by the Assad family.

The downfall of Assad’s totalitarian regime is not to be mourned – but what do we know of the Syrian rebels? This anti-Assad offensive has been led by Hayʼat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a Sunni Islamist paramilitary outfit currently led by Abu Mohammad al-Julani – previously an emir of the al-Nusra Front (the former Syrian branch of Al Qa’ida). Back in May 2013, he was listed as a ‘Specially Designated Global Terrorist’ by the US State Department – which in 2017, announced a $10 million reward for information that could lead to his capture. In the Home Office’s list of designated terrorist organisations, both al-Nusra Front and HTS are currently ‘treated as alternative names for the organisation which is already proscribed under the name Al Qa’ida’.

More recently, al-Julani has presented a more ‘moderate’ and ‘reformed’ version of himself – appearing to suggest that he has no intention to wage war against western interests and wishes to offer protections for Syria’s religious minorities (such as the country’s Shia, Alawite, Christian and Druze groups). But whether religious minorities are truly safe in a post-Assad, Sunni-led ‘Islamic Emirate of Syria’ remains to be seen.

All of this raises serious questions when it comes to the UK’s refugee and asylum policy. What has unfolded in Syria has been greeted with celebrations across Europe – especially among Sunni Muslim Syrian citizens who claimed they were at major risk of violence and persecution under the Assad regime. The former president hailed from the Alawite minority, with Alawism being a religious sect which splintered from Shia Islam in the ninth century.

There is an argument that Syrian Sunni Muslim refugees in Europe – including the UK – who have welcomed the HTS-led overthrow of the old regime would no longer face such risks of persecutory violence and intimidation in a post-Assad Syria. Indeed, the EU and the UK can be involved in the reconstruction of a new Syria – in the process, implementing the large-scale regulated return of anti-Assad Syrian refugees who do not have an indefinite right to remain in Europe. Refugee policy should be pragmatic – once it is relatively safe for refugees to return to their country of origin (perhaps as a result of regime change they personally welcome), this should be organised.

The worst-case scenario is if Syrian Sunni Muslim refugees who have welcomed the collapse of the Assad regime remain in their European host societies, while a new stream of Syrians flee to the continent and look to seek refuge in places such as the UK. This is anything but implausible, especially if we witness the arrival of an ‘Islamic Emirate of Syria’ which is defined by a Sharia-inspired model of governance administered by a Sunni Islamist regime.

Where would this leave Syria’s Shia, Alawite, Christian and Druze minorities? If they were to be provided sanctuary in the European societies where there are already a notable number of Syrian nationals who have celebrated the victory of a rebel force led by a Sunni Islamist militia group, the likes of the UK would essentially be importing a Middle Eastern civil war and bringing it to their doorstep.

The most sensible approach would be for the UK and its European partners to strike a pragmatic relationship with a new Syrian government – one that can secure the mass return of Syrian refugees who are supportive of the regime change, while being prepared for the possibility that there are religious minorities who may now feel deeply insecure in their homeland.

A more rational and hard-headed approach is required to have a truly effective refugee policy which prioritises cohesion and security. Syria is a golden opportunity for European governments – especially the UK’s Labour Government – to put this into practice.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.