The DUP is used to being loathed and ridiculed. Recently, the party has been attacked ferociously for its role in the botched Renewable Heat Incentive energy scheme at Stormont, its attitudes to social issues like same-sex marriage and the conduct of its North Antrim MP, Ian Paisley, who is subject to the first recall petition in Parliamentary history.

Sometimes, it can seem like the DUP is impervious to criticism, but the latest group to direct its anger at the party will be difficult to ignore.

The government is currently conducting a consultation into dealing with the legacy of the Troubles in Northern Ireland and many families whose loved ones were victims of terrorism are alarmed by the document. The proposals are based upon structures agreed by the DUP and Sinn Fein during negotiations for the Stormont House Agreement, signed in 2014.

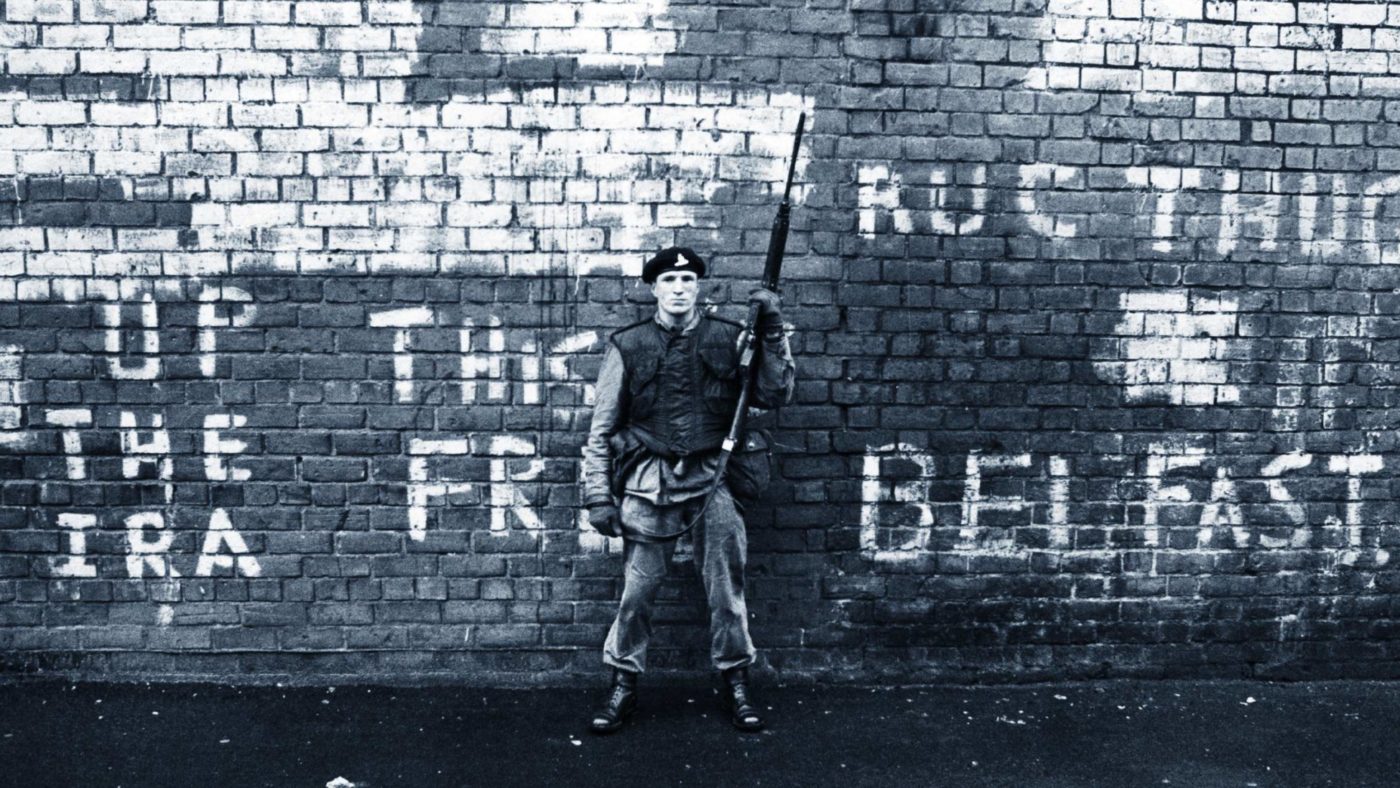

Groups who represent victims worry that the new Historical Investigations Unit (HIU), which is the centrepiece of the plans, will fail to bring perpetrators of terrorist murders to justice. They fear that a one-sided legacy process is being used to legitimise the IRA’s campaign of violence and portray the British state as the aggressor in Northern Ireland’s conflict.

Increasingly, they blame the DUP for failing to listen to the concerns of innocent victims and their frustration has spilled over at recent meetings, where party representatives have been accused of responsibility for the consultation proposals. During an emotional debate at parliament buildings in Stormont, organised by the South East Fermanagh Foundation, audience members asked the South Belfast MP Emma Little Pengelly pointedly and repeatedly whether her party had approved the legacy structures.

There is a perception that the DUP has focused on issues like an Irish Language Act and failed to address an imbalance in the way that the past is dealt with, during negotiations to restore power-sharing in Northern Ireland. In contrast, republicans and nationalists have campaigned incessantly for funding to complete inquests into a comparatively small number of killings caused by the police and army during the Troubles.

The Belfast News Letter reported that 40 of these coroners’ inquests, out of a total of 92, will investigate the deaths of terrorists, including, for example, 8 IRA men who were killed by the SAS at Loughall as they tried to bomb the local police station. This unit of the Provisionals’ East Tyrone Brigade was responsible for a series of brutal sectarian murders in border areas of Northern Ireland.

Of course, no inquests are planned into the killings committed by these glassy-eyed fanatics and others of their kind. It is far easier to pursue members of the security forces, who kept records as they endeavoured to prevent Northern Ireland from slipping into outright civil war and struggled to protect law-abiding citizens from terrorists who were determined to kill and maim.

When Theresa May suggested in the House of Commons that investigations into the past were targeting former members of the security forces rather than paramilitaries, a cohort of Ulster-based journalists rushed to refute this assertion, claiming that the PSNI legacy branch was dealing with 1,118 deaths, of which 352 involved the police or army.

To put this figure in context, the state was responsible for 10 per cent of the killings that took place during the Troubles and most of these will have been legitimate, yet all of them are being investigated. The IRA was responsible for two thirds of deaths, the vast majority of which remain unsolved. Just 45 per cent of the caseload involves these murders and the prospect that members or former members will be convicted is remote.

Dealing with the past in Northern Ireland might seem like an impossible task, but it is complicated further by a definition of victimhood that includes people killed or injured committing terrorist acts and the use of the word collusion to discredit almost every aspect of counter-terrorism undertaken by the security forces.

It is Sinn Fein and the IRA, as well as other paramilitary groups, loyalist and republican, who should be most worried about any process aiming to deliver truth and justice, yet its representatives are so relaxed about the current arrangements and the government’s latest plans that they constantly demand quicker and more thorough progress.

The HIU is supposed to address the imbalance in dealing with the past, but it is already committed to taking on the PSNI’s lopsided caseload and hundreds of allegations against the RUC, alongside investigating other murders. With its resources stretched from the outset, victims of terror have no confidence that it will deliver justice for their loved ones.

There is widespread weariness about talking about the past in Northern Ireland and even the DUP, whose critics often accuse it of being ‘backward looking’, is not immune from this phenomenon. The ‘peace-process’ has been nudged along by pardons and ‘comfort letters’ provided to members of the IRA who are suspected of crimes. It is assumed that, if the law is applied too thoroughly, senior members of Sinn Fein will be prosecuted and the power-sharing institutions will collapse for good. For the DUP, that would mean losing jobs and influence permanently.

Yet, even aside from the interests of victims, the struggle over the legacy of the Troubles has a meaningful impact on politics today. Sinn Fein’s attempts to portray the IRA’s campaign as a justified reaction to state violence are tireless and many young people, in particular, are persuaded that the “struggle” was a campaign for “rights” and “equality” denied by unionists and the British government. They are scornful of the idea that criminal violence in Northern Ireland was wrong and this lack of reflection often shapes their attitudes to the state and their unionist neighbours.

It is far easier to identify problems with the legacy process than come up with solutions. However, the University of Ulster academic Cillian McGrattan argues that the consultation proposals are based on ideas about transitional justice that are not applicable to Northern Ireland. He says they draw upon models used in countries where the state was the main perpetrator of violence and trust in the legal system had broken down.

In a new book about the subject, the journalist Ben Lowry, who has written about legacy extensively, suggests that the government should restore confidence in the process by setting up a time-limited inquiry into IRA violence. He believes that it might cost about £100 million, which would still be around half the price of the Savile Inquiry into Bloody Sunday.

This is the type of initiative that the DUP might at least have sought when it negotiated the Stormont House Agreement. If instead, the current consultation proposals are adopted and investigations into the Troubles continue to focus on killings by the police and the army, then the party will have let down the victims of terrorism and damaged the prospects of a stable, harmonious society in Northern Ireland.