Growth seems nowadays like a distant aspiration. We are not in recession only on a technicality – we missed it by 0.3 GDP percentage points over the last two quarters, equivalent to less money than we spend on the NHS every ten days. Worse still, GDP per capita – arguably the more important measure – actually fell by 0.4% in the same period. And things are not set to get better. Despite the Labour Government’s pre-election promise to fund increased expenditure through growth, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), growth is not set to surpass 2% a year over the next three years.

Indeed, recent fiscal events – both the Autumn Budget and the Spring Statement – have done little to help. The OBR estimates that, over the next five years, recent decisions by the Labour Government will only improve GDP by 0.2% (that is 0.2% overall, not per year). Of course, the OBR’s predictions are far from perfect – the body consistently overestimates growth, suggesting that actual growth will likely be even poorer. No wonder we have recently seen pro-growth organisations such as Looking For Growth and Centre for British Progress flood our social media feeds.

But it has not always been like this. In the years following the Second World War, our economy – as well as the economies of other western powers – was booming. Between 1960 and the 2007 financial crisis, our GDP per capita grew at an average rate of 8.3% per year. Growth was easy to come by and governments did not have to try very hard at all to benefit from it. Tony Blair is a good example of this. GDP per capita doubled over his time in office, and the voters rewarded him with three consecutive general election victories, but Blair was riding on a worldwide wave of good economic news. In that same period, the American, French, German and Italian economies – as well as many others – all also saw their GDP per capita increase by more than half.

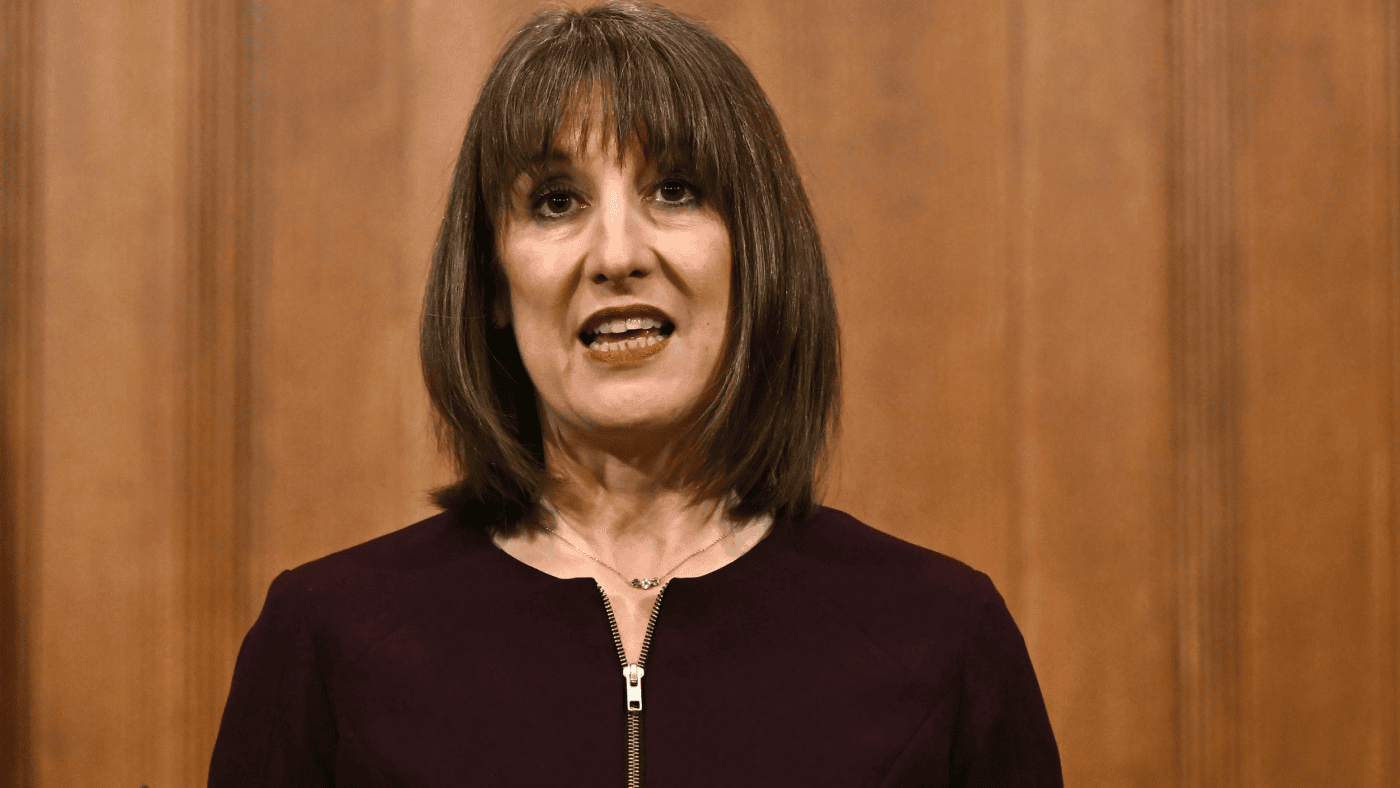

Growth is important because, although GDP numbers might seem to have little direct impact on the lives of ordinary people, they correlate with several things that do. As Rachel Reeves had found out making her Spring Statement, without growth, it is extraordinarily difficult to improve living standards, wages or public services. Similarly, to reduce poverty, fund the military or build houses. Money for all those things must come from somewhere and, without growth – which indicates that there is more value in the economy as a whole – more money for any one thing generally means less money for something else.

But, to be fair to Reeves, she has been dealt a very bad hand. Today, no matter what the Government does, growth is likely to remain poor. This is for a few reasons. First, our low birth rate means that we have increasingly few working people as a proportion of the population. This means fewer things being made and fewer taxes and wages being paid. It also means the state needs to spend more on healthcare and pensions when it could be spending money on things that are better for growth, like infrastructure. But the decrease in the birth rate is part of a global trend that is largely outside of the Government’s control. The high cost of energy across Europe does not help either, but developing our own energy infrastructure would take decades. The UK, together with many western European countries, is also plagued by a heavy-handed, risk-averse regulatory culture. Adding to these long-standing problems, Trump’s tariffs will inevitably shrink the world economy.

To even attempt to alleviate those problems would take years, if not decades. In the short term, we need to satisfy ourselves with making the best of our poor situation. It may be tempting to try untested and radical solutions – get rid of the political establishment and replace it with an altogether new alternative. This is what Reform offer. It is also what Corbyn tried to offer, and what many people in the Labour Party may wish to replace Starmer’s Government with. All over Europe, populists are gaining traction, reflecting on the public’s dissatisfaction in low wages, high costs of living and underperforming public services. But to make the best of our poor situation, we should not fall prey to such temptations. Yet-unpublished research from Bright Blue shows that one form of government – the centre-right – has consistently overperformed European rivals where it comes to growth.

Over the course of the last seven decades, economic growth under centre-right governments has been consistently higher than under the centre-right’s left-wing or populist rivals. France is the best example of this, with annual GDP growth under centre-right rule being on average 1.7 percentage points higher than under their main rivals, the French socialists; but the centre-right presides over superior growth in every country we have studied, including Germany, Ireland and, indeed, the UK. This is not a coincidence – centre-right governments combine a respect for the markets (uncharacteristic of socialists) with respect for the institutions (uncharacteristic of populists) that keep markets well-oiled and secure. In the UK, the Tories remain the traditional abode of the centre-right, but Starmer’s Government has clearly been influenced by centre-right ideas – demonstrated, among others, by its commitment to fiscal sustainability. This Government is doing the right things on planning and infrastructure. Yes, things could be better, but they could also be far, far worse.

It might be tempting to give up on the centre-right. History shows that – at least where it comes to economics – it remains our best bet.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.