We live in a world where politicians and campaigners define themselves as pro-market or pro-state. Academics, meanwhile, are increasingly specialists in narrow and very specific corners of their subject area. And nearly all of public debate is materialist – with huge attention given to our status as employees, entrepreneurs, taxpayers, welfare recipients, public sector workers or litigants.

There’s very little focus on our relational existence and how our role as parents, neighbours, volunteers, churchgoers or trade unionists might be protected, or even enhanced. The invisibility of these ties of blood, locality, faith and cause – all of which bind to socially important effects – is illustrated by the lack of any serious attempts to even measure changes and inequalities in social capital.

In this artificially divided, heavily materialist and mismeasured world, Michael Novak was a watcher and describer of the wood rather than the trees. While he believed that capitalism was superior to other forms of economic organisation, because of the ways in which it rewarded human creativity, he argued that the free enterprise system provided roughly only a third of what produced fair, strong and morally content societies.

He was a capitalist who understood the importance of the courts, of anti-monopoly policies, of the state guaranteeing a safety net for the poor and vulnerable, of a free press, of strong family networks and of people-sized institutions that were human enough to treat individuals as individuals rather than as accounting units.

For Margaret Thatcher, he “provided the intellectual basis for my approach to those great questions brought together in political parlance as ‘the quality of life’”. And this American Catholic of Slovak heritage is also credited with moving John Paul II towards the more sympathetic account of free enterprise contained in the papal encyclical Centesimus Annus – published shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, when some were talking giddily of capitalism’s “end of history” triumph.

Such complacency would not have appealed to Novak. In part, this was because of his awareness that most economists and most advocates of capitalism were not just ill-equipped to explain why Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” led to moral as well as material enrichment – they didn’t even see much of a need to do so.

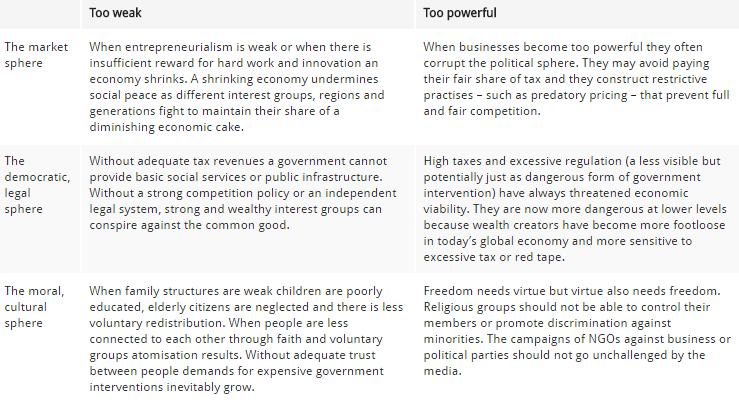

Novak’s 1982 work, The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism, from which his high status in Downing Street, the Vatican and many other centres of power flowed, stood very much in the mould of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations and Theory of Moral Sentiments. At least as interested in moral argument as practical economic workings, Spirit placed the capitalist system within a political and cultural context and made the case that trouble inevitably resulted when market, democratic, legal and social structures were either too strong or too weak.

Professor Novak, a deeply committed Catholic, met his Maker two weeks ago, aged 83. Scandalously few column inches remembering the man and his works have been buried underneath a Milo of Yiannopoulosity – all only serving to confirm the continuing Trumpification of US conservatism and, equally as concerning, the descent of many once proud news organisations into ratings-chasing branches of the entertainment industry.

Novak would have been disappointed, but not surprised, at Milo-isation – and its Coulter-isation overture. The possibility that movements as well as nations and individuals can either mend their ways or completely lose the plot within the space of just one generation was central to this Catholic professor’s theology.

Simultaneously, he recognised the almost boundless creativity in human beings, made as we are in the image of God, but also knew that, as descendants of Adam and Eve, we are all equally capable of eating forbidden fruits with disastrous consequences.

This realistic view of both human potential and frailty meant he was never a one-eyed zealot for laissez-faire, state intervention or any other simplistic one-club, one-bullet or one-ideology approach to public debates.

He might not have been the compelling moral advocate for “democratic capitalism” that he became if he hadn’t – as “a good Christian” – begun on the Left. In his own words, “business was merely buying and selling, mere hucksterism, after all”.

As the seduction of the Left’s heart-on-sleeve morality began to meet the reality of poor practical results, however, especially in the Communist-run nation of his parents’ birth, his view of commerce evolved too.

It increasingly resembled the understanding articulated so eloquently by Quintin Hogg, Baron Hailsham of St Marylebone. The Lord Chancellor for Mrs Thatcher’s first two terms declared that “the great advances which have been made in human happiness have been just as much due to the spinning jenny, the internal combustion engine, and the generation of steam as to the moral sublimity of a Shaftesbury, a Florence Nightingale, an Elizabeth Fry, or a Mother Teresa”.

And this takes us to what, in a completely inadequate acknowledgement of the nearly 40 books that he either wrote or edited, are three great lessons from Michael Novak’s works.

One was aimed at the Communists of his day – and could be aimed at the crony capitalists and corporatists of our own. This was that human ingenuity is what makes capitalism most special.

The second was the importance of reaching out to those, like his young self, who saw capitalism as morally deficient.

And the third was a message to anyone tempted by free-market fundamentalism – that free markets depended upon social and democratic values that are generated from other sources.

Lesson one, then, is that the X-ingredient within capitalism is “caput” (Latin, literally meaning “head” and by metonymy “top”). Throughout history there have been many attempts to explain the success of economies where freedom of individuals and private businesses were maximised. Some have emphasised institutions and arrangements like limited liability. Max Weber, perhaps most famously, saluted the Protestant work ethic.

Novak, partly because of his eastern European origins, knew that while a propensity to hard work was a powerful force for social good, it was not enough if the system as a whole, as was true under Communism, crushed human “wit” – ie the human capacity to invent, to innovate, to discover, and to organise in new cooperative ways. “The cause of the wealth of nations is caput,” said Novak in a speech that he made in 2004 to the Mont Pelerin Society on the moral case for capitalism.

On another occasion he explained: “Capitalism teaches people to show initiative and imagination, to work cooperatively in teams, to love and to cherish the law; what is more, it forces persons not only to rely on themselves and their own moral qualities, but also to recognise those moral qualities in others and to cooperate with others freely.”

His diagnosis of capitalism was very Smithian. It focused on how the pursuit of self-interest led people to produce things of benefit to others and that a maximised number of free, entrepreneurial citizens, rather than a centralised economic power (the state or – often overlooked – a large, bureaucratic private company), was best placed to identify the needs and wants of diverse individuals and communities.

And this would only happen if there were adequate rewards via pay, investment dividends, profit, protection of intellectual property and the like for doing so.

Here is our second Novakian lesson: that capitalism needs a moral defence. Moreover, it may need more of a moral defence than most other ideas, because it only thrives by utilising the more self-serving and sometimes less-than-elevating instincts of humanity.

Having embraced the Left in his younger years, because of what he saw as commerce’s ugly side, Novak knew the moral unattractiveness of capitalism’s dependence upon what Gordon Gecko of Wall Street fame called “greed” – or, if you prefer, we could more delicately call self-interest.

Adam Smith was himself clear that generosity didn’t drive the wealth of nations forward, noting that it’s not from the benevolence of the butcher, the baker or the brewer that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.

In other words, in a typically colourful quote attributed to John Maynard Keynes: people might be impressed with the results of the capitalist process, but are perturbed and even repulsed by the means via which “the nastiest motives of the nastiest men somehow or other work for the best results in the best of all possible worlds”.

It was no surprise that at the end of the 1980s and in the early 1990s, when the triumph of capitalism over Communism as a functioning, delivering system was widely accepted and emulated by even the once-reddest Marxists, the Western Left fell back on critiques of capitalism as “loadsamoney”, selfish and corrupting of virtue.

Novak’s defence had many dimensions, but it was his presentation of capitalism as just one of three essential spheres that was central to his writings and which was so different from politicians immersed in anti-state or anti-market intellectual bunkers – and from academics lost in the weeds of one narrow field.

Lesson three from the books of Novak is that while capitalism may be the best system for producing wealth because of its recognition of and reward for human ingenuity, it’s not particularly good at nurturing the kind of adult citizens that make good workers or honest taxpayers. That’s primarily the job of parents (or, as Hillary Clinton would insist, villages).

Neither is it as good at distributing wealth as creating it. We need the state to ensure a minimum living standard for everyone.

When so many politicians and thinkers tend to identify as narrow defenders of the market or the state, Novak insisted both had important functions.

And, equally important, in a world where capitalists and statists are often just different branches of materialism (its production and distribution thereof) – seeing human beings only as investors, bankers, shareholders, labourers etc on the commercial side and as taxpayers, public sector employees, welfare claimants, lawyers and the like on the statecraft side – the “Spirit” of Democratic Capitalism was a reminder that non-market and non-state actors such as parents, religious communities and free media had vital roles to play too.

If the economic sphere became too dominant, we risked inequality and the crushing of competition by the rich and powerful. If the state became too big, we risked economic stagnation and a loss of freedom. And if agents of the third moral, cultural and social sphere gathered too much power, we ended up with a theocracy or a land run by unions or by whatever social organisation had attained inflated prominence.

The kind of problems that arise when the market, the democratic state or the third social sector become too strong or too weak are set out in the table below that I produced a couple of years ago for the Legatum Institute.

And by way of footnote, one striking feature of the obituaries and reflections that have appeared in the press and online since Professor Novak’s passing has been a consistent recognition of the man’s kindness and good character.

I had a small experience of this when he was a guest of the IEA Health & Welfare Unit (which became the Civitas think tank) in the late Eighties and early Nineties.

I was a student at Exeter University and had travelled to London to hear him speak at the QEII Conference Centre. His deep interest in the social architecture between the individual and the state was compelling to me – especially as I had been studying the Church of England’s “Faith in the City” report and its lazy regurgitation of the false duopoly of state vs market.

I remember standing awkwardly alone in the corner, nursing a drink and watching the great and good of Britain’s centre-right enjoy the reception given in the great American’s honour. I hoped I might talk to him, but lacked the confidence to interrupt the throngs of journalists, MPs and the like who surrounded him.

But, all of a sudden, he had disappeared. I scanned the room to see where he’d gone. And then he was next to me. While I had been invisible to nearly everyone else, I hadn’t been invisible to him – and for the next 10 minutes he insisted I tell him what I liked most and least about his lecture. I could tell he was actually listening.

I was reminded of that brief encounter with Michael Novak when I was reading the Washington Post‘s obituary of him and his attempt in one book to explain what God was like. “He is not ‘the Big Guy upstairs’, nor the loud booming voice that Hollywood films affect for God… There are hosts of bogus pictures for God: the Watchmaker beyond the skies, the puppeteer of history.”

He continued: “If you wish to find him, watch for him in quiet and humility — perhaps among the poor and broken things of earth There are people who looked into the eyes of the most abandoned of the poor and saw infinite treasure there, treasure without price, and there found God dwelling.”

Novak is with that infinitely compassionate God now and it’s up to us to fight his battles for capitalism.

Against all that discourages “caput”, including confiscatory taxes, expensive regulations and big businesses with monopolistic power. Against the free-market fundamentalists who, unlike Adam Smith, overlook the “mean rapacity”, “mean and malignant expedients” and “sneaking arts” of many merchants and manufacturers – and consequently deny the corrective, civilising and compassionate functions of limited government, courts and of civil society. And against complacency.

Because capitalism is powered by self-interest and even greed, it is supported because of its track record of creating more jobs and wealth than alternative economic systems, rather than because of admiration for the behaviour of its leading participants.

This grudging and conditional acceptance means that the capitalist and capitalism enjoy little benefit of the doubt when shocks occur or if there is a downturn in the business cycle.

Supporters and leading beneficiaries of the system need to work harder to tackle the ignorance of capitalism’s achievements and of the weaknesses of the alternatives – but greater philanthropy and social responsibility might also be a leading way through which businesspeople can protect themselves from political risk.

If the public sees free marketeers as “basically a bunch of psychopaths running around trying to line their own pockets” – to use the words of John Mackey, CEO of the Whole Foods supermarket – don’t be surprised if one day the public call for the psychopaths to be stopped, and stopped dead.