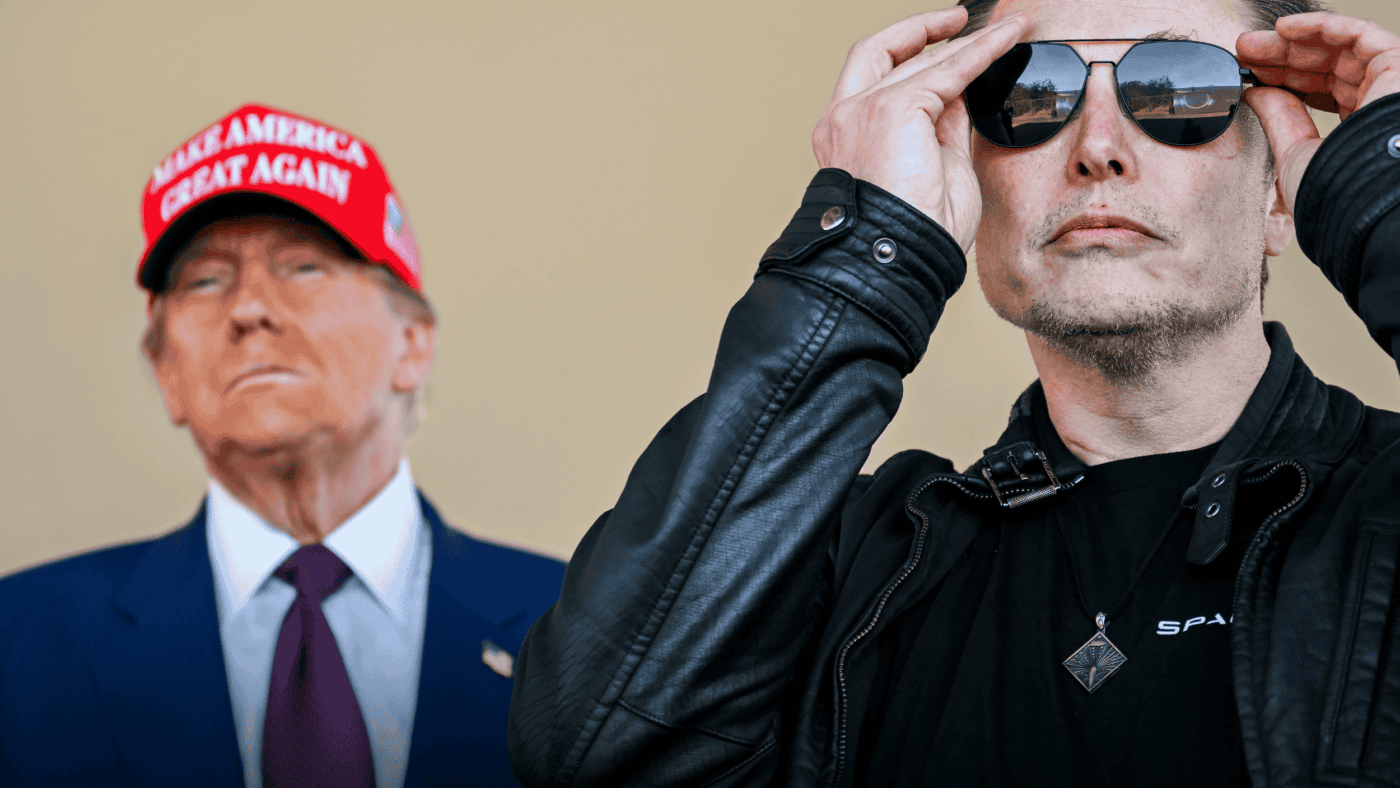

Donald Trump’s inauguration as President of the United States last month was rich in symbolism. One of the most striking images was the parade of ultra-rich technology entrepreneurs who had declared their support for him. Most prominent was Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla and named by Trump as head of the Department of Government Efficiency, but he was joined by Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Meta and Facebook; Apple chief Tim Cook; Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon; Google’s CEO Sundar Pichai and co-founder Sergey Brin.

This claque of business leaders is a sign of Silicon Valley’s changing allegiances, as the tech community used to be dominated by modern-minded centrist liberals who supported the Democratic Party. Some, no doubt, have made a brutally rational assessment of the way the political wind is blowing, and it suits Trump to align himself with these innovative, risk-taking, hugely successful disruptors. The message is obvious: the president is a deal-maker, standing outside the political mainstream and promising wholesale change.

It is easy to take this narrative as a given. After all, Donald Trump is the only president never to have held political office or high military rank before occupying the White House, and his fame is rooted in the world of business. But it is mistaken to think that he is cut from the same cloth as Musk, Bezos, Zuckerberg and the others doing homage. His instincts and conception of the world are significantly different.

Trump has no rags-to-riches backstory. His father, Fred Trump, was a property developer who worked in construction and sales before creating a business empire which would become the Trump Organization. Donald was named president of the company at the age of 25, and when Forbes published its first 400 Richest Americans in 1982, father and son were listed as sharing a fortune of $200 million (around $650m today).

Property remains the foundation of Trump’s wealth. He is a rich man who has undoubtedly made himself richer, estimated to be worth anything between $4 billion and $8bn (though of course he claims various much higher figures). The Trump Organization derives perhaps 80% of its value from property and commercial ventures like hotels and golf courses, while, by contrast, many of the president’s more eye-catching ventures have ended in failure: Trump University, Trump Magazine, Trump Shuttle, Trump Steaks. He is in many ways an old-fashioned businessman, exploiting one of the oldest sources of wealth.

It was because of this, not in spite of it, that producer Mark Burnett approached Trump to star in his new reality television show The Apprentice. Burnett saw him almost as a caricature of a bombastic, high-living plutocrat, dominating a boardroom, firing those who failed to make the grade and exhibiting a relentless will to succeed.

This plays into another facet of Trump. The president is a nationalist and a populist with a driving need for affirmation, and he sees the world in stark terms of winners and losers, good guys and bad guys, success and failure. This means that for him trade deficits and high levels of immigration are signs of weakness, demanding swingeing tariffs and strictly controlled borders. His sense of national prosperity and strength are explicitly retrospective – the fourth word of his mantra ‘Make America Great Again’ is significant – and he conjures up an image of America in the 1950s and 1960s, powered by heavy industry like steel, oil, coal and automobiles. He is a president for the Rust Belt.

What modern entrepreneur shares this world vision? To take immigration, look at the guests at the inauguration: Elon Musk was born in South Africa, Sundar Pichai is Indian, Sergey Brin is Russian and invited-but-unable-to-attend Shou Zi Chew, CEO of TikTok, is from Singapore.

The tariff to which Trump is so devoted, calling it ‘the most beautiful word in the dictionary’, is essentially designed to distort competition, protecting domestic industries. Is this the entrepreneurial spirit, increasing costs on American consumers to keep sectors like oil and automotive manufacturing alive artificially? Tesla, Inc., Elon Musk’s thriving electric vehicle and clean energy company, has factories not only in the United States but also Germany, the Netherlands and China. Google has offices in more than 50 countries.

We should not assume that Trump’s second administration will be a lean, responsive, hyper-efficient machine reconfigured on business lines. The president is a screen character, a cosplay tycoon confected for his public image. ‘Tech bros’ may be clustered around him and paying court but they do not see a kindred spirit, rather a source of power and patronage.

Donald Trump makes great play of his 1987 memoir-cum-self-help guide ‘The Art of the Deal’, and we should pay attention too, because it is significant. According to the book’s ghost writer, Tony Schwartz, Trump’s involvement was extremely limited. In the words of Howard Kaminsky, chief executive of the book’s published Random House, ‘Donald Trump didn’t write a postcard for us!’

That is his secret. He is playing a part. He and his billionaire allies have entered a marriage of convenience, and we should not mistake it for a love match.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.