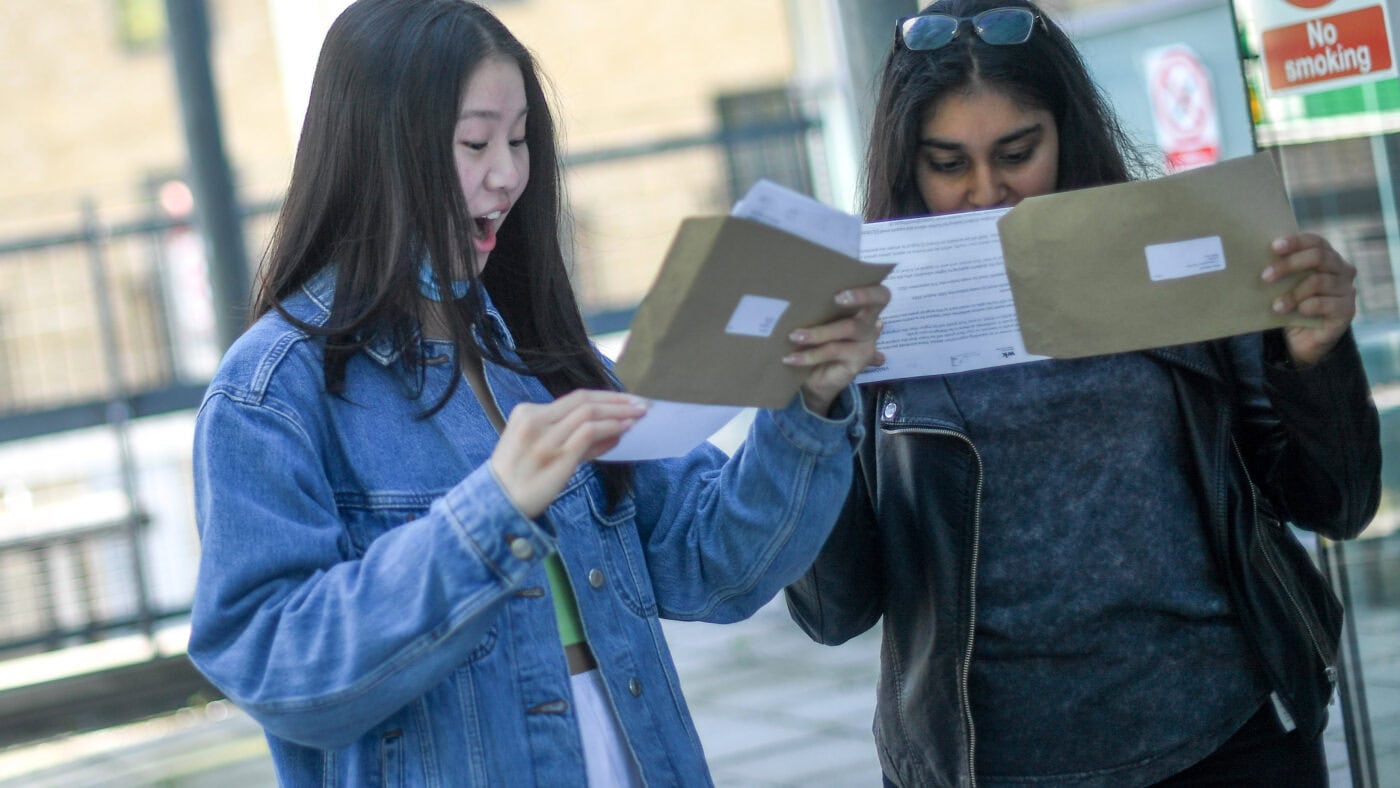

There will be much to be written about today’s A-Level results, but there is definitely one aspect of the higher grades that is worth celebrating: applicants having more leverage when it comes to pursuing their university offers. From The Daily Telegraph:

A record number of pupils are also expected to use the clearing system to ‘trade up’ their university offers, and many Russell Group institutions have saved space for high-performing students.

Top universities reported receiving hundreds of phone calls this morning as top-performing pupils tried to cut a better university deal.

Whether or not the bigger picture is good is a separate discussion. In addition to a bumper crop of As and A*s, the other factor which has made so many additional clearing places available is a shortfall in international students following the previous government’s efforts to tighten the rules on visas.

Such initiatives are overdue; Neil O’Brien set out how people are using the sector to do and end-run around immigration requirements, and academic sources tell me that some universities’ overseas marketing strategies still seem to be selling an immigration pathway more than a degree.

That’s good news for domestic applicants, at least in the short term – but will only sharpen the financial pressures on universities. According to research from the Russell Group, institutions lose money on every category of British undergraduate, and the margin is trending up. But just as with the thorny question of the graduate premium, the interests of the sector (and indeed, of the taxpayer) and the interests of individual students do not always line up.

Moreover, giving domestic students a stronger hand helps to palliate the deeply, deeply problematic institution into which clearing has evolved since the government lifted the cap on student places in 2015/16.

At first glance, it might not be obvious to those unfamiliar with the issue why clearing would be unethical. The attitudes of many will still be shaped by the old system, where it did tend to be, as one academic put it to me, ‘about helping someone who just didn’t get their B in maths’.

But that was then. Today, clearing is where distressed teenagers who missed out on their results are given the hard sell by academics drafted into their institutions’ call centres, many of whom are very keen to talk students through the door. Again, interests diverge: even if the Russell Group numbers are right, the cost implications for an extra student are very different for a university and for a particular department within it.

On the other side, young people will often find themselves being pushed as much as they’re being pulled, both by growing parental expectations of going to university and by schools, which in addition to being staffed almost exclusively by graduates, are publicly assessed on the share of their pupils that proceed to higher education each year.

The result is a system that seems too often to work on the principle that it is better that a young person go somewhere, anywhere, rather than take a year out to re-sit some exams and consider their options – a principle that serves the interests of the schools and universities, but much less obviously either the taxpayer or the student.

After all, there is no discount for a place secured through clearing. Going to university is still the largest financial decision, by a very large margin, that most young people will have made in their lives up to that point; for many, it will retain that title. They are taking out a mortgage for almost £28,000, secured against a lifetime extra tax obligation on their future income; the successful will end up paying back far more than the face value, although of course none will have the experience with borrowing and finance that makes this obvious.

Tuition fees are problematic. There is a reason we have not, even at a time of stretched public budgets, expanded the practice of funding the public sector by selling five-figure lottery tickets to teenagers. But at least in the normal run of events, a pupil has time to make a considered choice, to think about the subject they want, visit universities and see which ones they like, and (if they’re so minded) investigate the likely graduate premium of different options.

Someone shunted into clearing with disappointing grades has no time to replicate any of that. Even more than the average school leaver, they are buying blind. Their position is further weakened when every source of authority and advice, most obviously their school and parents, are likely pushing them to go somewhere.

Place a buyer under great pressure to settle, deprive them of the information they need to make an informed decision, and make the cost less tangible by fronting them the cash no questions asked (it’s not enough remarked upon that tuition fees operate on the same model that Klarna uses to sell handbags). It’s no surprise if they end up taking a poor deal.

So even if you are concerned about the financial viability of the sector, or about the real value of sending as many people we do at university, there is at least in today’s results something to celebrate. As long as we insist on selling higher education to young people the way we do, morality should demand they have as strong a hand as can be dealt them.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.