The year is 1980, and 44 years have passed since Britain’s socialist revolution. A new generation has grown up, which has no active memories of capitalism, and only a hazy concept of what ‘capitalism’ even was.

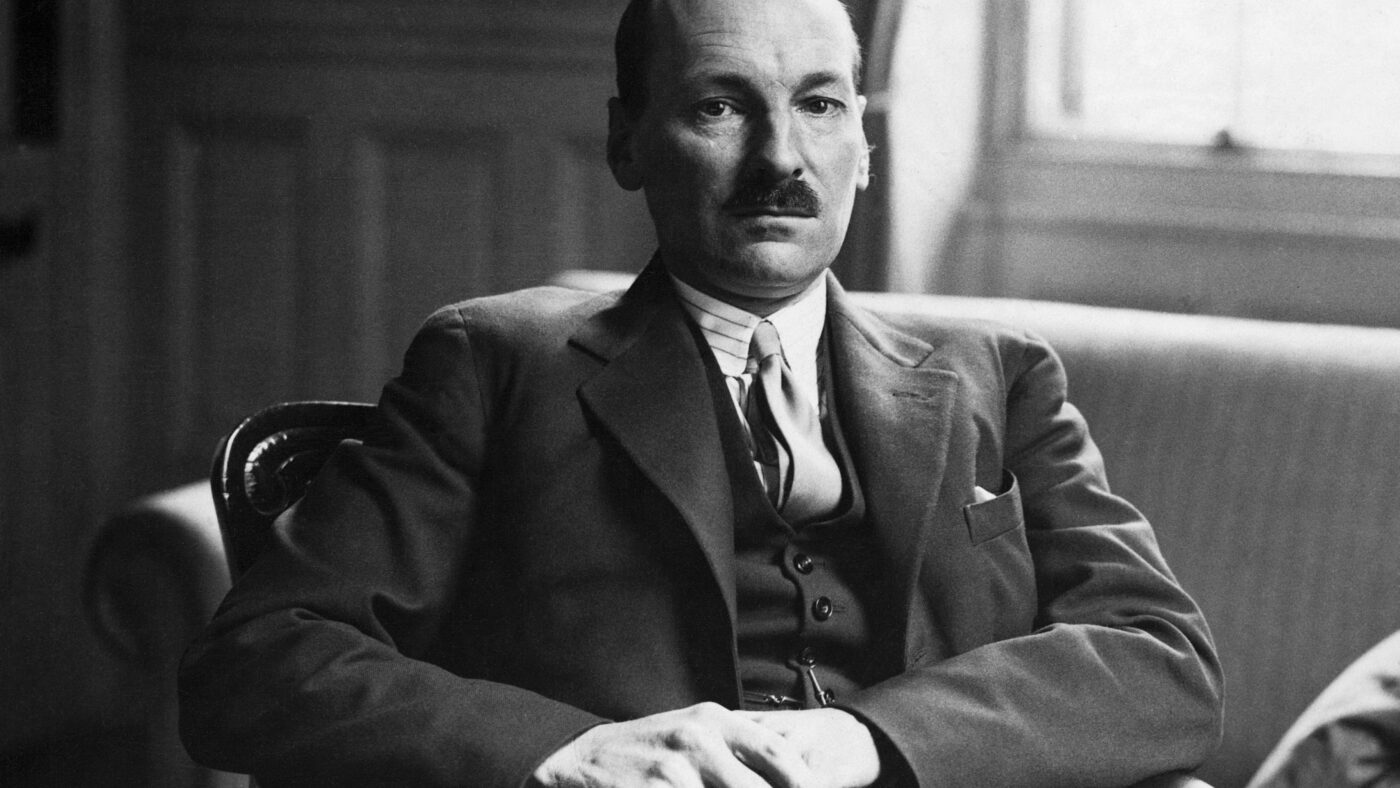

This is the premise of the book ‘The First Workers Government‘ by Gilbert Mitchison, published in 1934. An unnamed narrator from that future then looks back upon the bad old days of ‘late capitalism’, and tells the story of how the people’s paradise was built.

It is a weirdly fascinating book. For those of us who do not believe in socialist economics, it reads like a description of a world where fish walk around on land, or where the sun is inhabited. And while the future imagined by Mitchison obviously did not come to pass, the book is nonetheless teeming with policy ideas that are still around today.

Here’s what happens in this timeline. The Labour Party is taken over by its most left-wing faction: imagine a 1930s version of Corbynism. They then win a general election in 1936, on a platform of breaking with capitalism once and for all. After taking office, they immediately abolish the House of Lords, impose strict capital controls to prevent capital flight, and socialise the financial sector. But they do all this in an orderly British way, respecting all the legal rules and procedures. All nationalisations come with compensations for the expropriated owners.

What happens next reads superficially like a preview of Clement Attlee’s government, because all the nationalisations that would really happen between 1945 and 1951 (eg. coal, steel, iron, railways, road transport, civil aviation, electricity, gas, healthcare…) also happened in this book. But that does not make Mitchison a prophet. The apparent overlap simply results from the fact that Mitchison’s fictitious socialist government nationalises everything. Not every nationalisation is explicitly described in the book, but where the continued existence of a private sector is tolerated, the narrator makes it clear that this is meant to be a stopgap arrangement, with full socialisation of the entire economy as the end goal.

Alongside this wave of nationalisations, an extensive new economic planning infrastructure is set up, the workings of which is described in sometimes tedious detail. Mitchison did not envisage his socialist state to be hyper-centralised. Instead, Britain adopts a form of devolution which is arguably better than the one we actually have today. More than 60 years earlier than in our actual timeline, Scotland and Wales get their own regional parliaments and devolved powers. But in addition, England is subdivided into six semi-autonomous regions with their own parliaments. Northern Ireland merges with the Republic of Ireland, which, like Britain, also adopts socialism. There is a socialist revolution in Germany too, which is neat, because it means that World War II never happens. Then in the mid-1940s, Canada and Australia go socialist as well, and join a defence union with Britain and the Soviet Union.

But back to the economics. Mitchison’s narrator describes the capitalist industries of the mid-1930s as haphazard, chaotic, short-termist, and lacking in overall coordination. The conventional Marxist critique is that capitalism leads to excessive market concentration, leaving us with a few mega-conglomerates controlling the entire economy. Curiously, Mitchison’s critique is the exact opposite: he castigates capitalist industries for being far too fragmented, failing to make use of economies of scale and economies of scope. So in his version, nationalisation leads to big productivity boosts, because it gives the government the opportunity to finally restructure all these inefficient industries.

Mitchison’s government is not an authoritarian one. It does nationalise the press, but it does not use those powers to control the content of what is being said. People are allowed to criticise the government in the government-owned press. It is just that few people want to do that, and there is no demand for it anyway. Socialism delivers, and the sceptics are quickly won over. The opposition parties also give up on trying to restore capitalism, and resign themselves to criticising details here and there.

And this is, ultimately, the problem with the book: it simply assumes away all the difficulties which we now know would later afflict actual socialist societies, and which were already afflicting the Soviet Union even at the time. If you simply assume that governments can run an economy efficiently, that this process can be meaningfully democratised, and that there will be no opposition, then yes, you can describe a viable model of democratic socialism. Just like you can describe time travel or encounters with supernatural beings.

Mitchison himself was not an especially influential figure, but his thinking was fairly mainstream among of left-wing intellectuals of his day. The political programme developed in this book does not come out of nowhere. As he says in the foreword: ‘I have adopted freely the ideas and proposals current in modern socialist literature, pamphlets, journals and speeches’. Nor did he think this was just utopian fantasy with no chance of getting adopted: ‘[W]hile the programme presented has no sanction from the Labour Party […], it is none the less intended to be such a programme as might now be accepted by the ‘left-wing’ of the Party and as might actually be carried out by the next Socialist Government.’

In 1945, 11 years after the publication of the book, Gilbert Mitchison became the MP for Kettering, a seat he held until 1964. As Baron Mitchison of Carradale, he then became a member of the House of Lords. If you cannot beat them, join them.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.