One of the surprise bestsellers of the summer was a book on assessments. Admittedly, Sammy Wright’s ‘Exam Nation’ won’t hit the same sales figures as Richard Osman’s latest whodunnit, but to have any book on this rather dry topic reviewed in The Times (by Michael Gove), The Financial Times (by Melissa Benn) and The Guardian (by Fiona Millar) is impressive, and that was before Radio 4 announced it was making it their book of the week.

Predictably, Gove saw the book as a reinforcement of the need for high-stakes examinations, while Benn and Millar saw it as something more progressive. We see what we want to see, and what we’ve experienced personally, when we stare into the examination room.

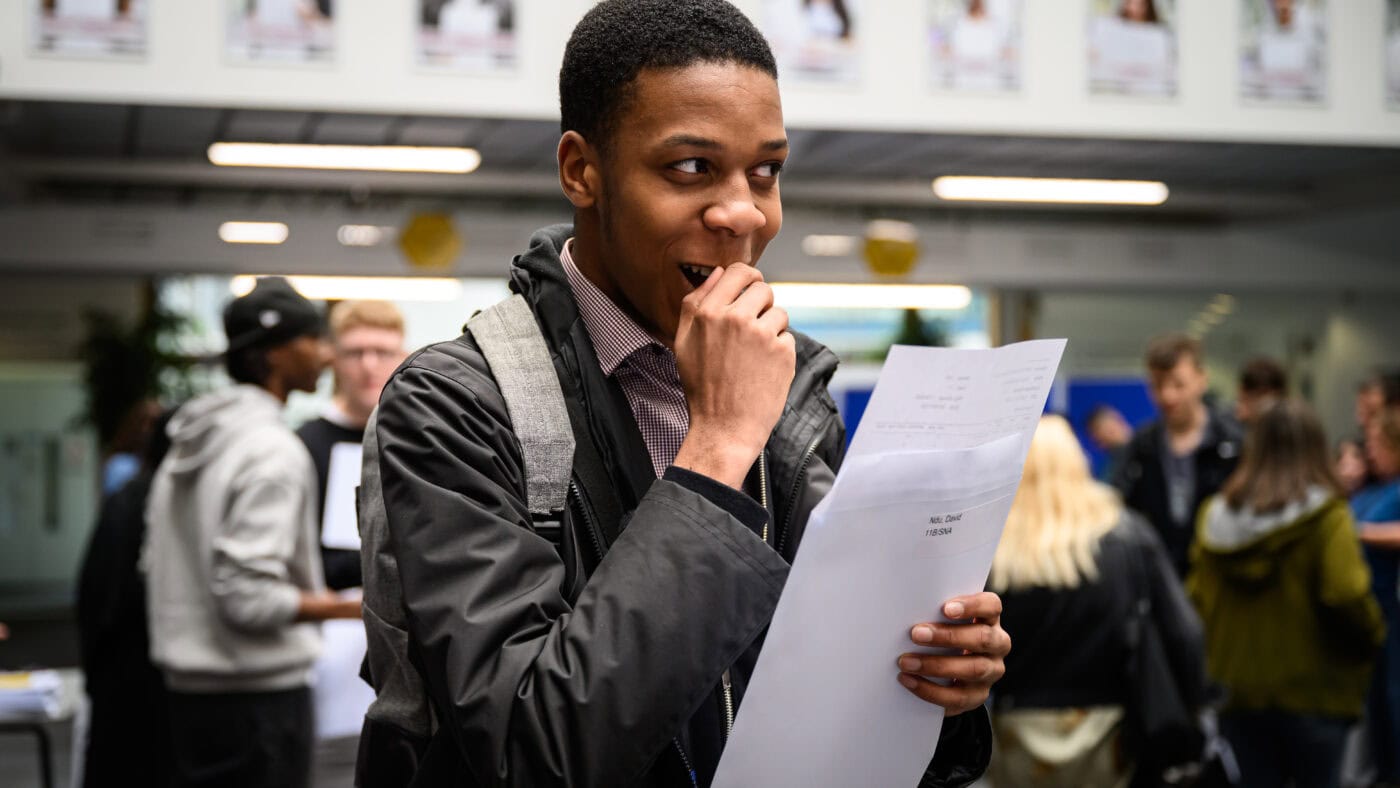

The book is a valuable contribution to the debate, and very well timed: last week saw A-level results published, and today is the turn of GCSE students to find out whether the work they have done over the last two years had been rewarded by the grades they received. As it turns out, in most cases they were.

While most pupils did indeed pass, there have been a number of calls for the country’s examination system to be overhauled, or scrapped altogether.

The United Kingdom has a neurotic relationship with examinations. Long gone are the days when getting high grades at 16 were a rarity, and the urge to have more inclusive (or less intimidatingly academic) examinations resulted in the creation of GCSEs in 1986. The abolition of O-levels was led not by some lily-livered left-wing secretary of state, but by Keith Joseph, and it was that rare piece of legislation that was actually welcomed by Fred Jarvis, the grizzled leader of the NUT, who declared: ‘this is one decision of Sir Keith’s which will be applauded throughout the teaching profession’.

No doubt such an endorsement rang some alarm bells in Number 10. And so it should have. Every reform to public examinations, relating to SATS, GCSEs or A levels, results in polarised debates about the nature of assessments, and whether they are fit for purpose, and if trade unions are in agreement with a Conservative Secretary of State then the legislation needs further scrutiny. There are many reasons why examinations have proven so divisive.

Firstly, in education, everyone’s an expert: we have all been in that lonely examination hall, and so we all feel we are highly qualified to argue on every aspect of this rather complex subject. Governments have played around with both sets of qualifications, resulting in grade inflation and dumbed-down content. GCSEs, more than A-levels, are perfect illustrations of how not to design a national qualification: they are a confused mix of modular examinations and coursework, and all completed in a very tight timeframe.

Radical reform which solves their innate weaknesses is unlikely because, as Professor Becky Allen has recently written, it is too complex, and too bound up with school accountability and the shape of the school day. Nobody has the appetite (or the money) to do this, and so we just fiddle around the edges. GCSEs are the educational embodiment of this country’s ongoing inability to think imaginatively and plan for long-term, beneficial reform.

It is also the case that examinations have become highly politicised, and the trends they reveal are often uncomfortable for Ministers. Since Joseph, there has rarely been an education secretary (or prime minister) who could resist partially reforming assessments (and the National Curriculum) in order to drive their own political agendas. Too often examinations and curricula are seen as levers for social change: only this week, Lee Elliot Major, Professor of Social Mobility at the University of Exeter, has called on the Government to end ‘the national scandal’ of a fifth of 16 year-olds leaving school without a GCSE in English or Maths. He argues that those who did not pass English and Maths were, by the age of 17 and 18, twice as likely to be cautioned by the police.

So, is the simple answer to make these exams easier to pass? To be more inclusive? It’s easier to do this, and persuade yourself and your fellow MPs that something has been done, than to try to address the more complex, messier, reasons why kids who underachieve at school may find themselves in trouble with the police.

It could be argued that the same is true of independent schools: if they continue to get (proportionally) more top grades that state schools, then instead of trying to fix issues in the state sector it is easier, and more politically expedient, to make it more difficult for private schools to operate, either financially, or by other means.

But examinations should not be political footballs, and reforms to the curriculum should not be driven by external factors about inclusion and diversity. Pupils should study a knowledge-rich curriculum that exposes them to the most important ideas, and greatest thinkers, in each subject they study.

When Labour were last elected, one of Gordon Brown’s first decisions was to make the Bank of England ‘operationally independent’. Brown referred to the Bank being ‘set free’. In comparison, this Government seems more statist by inclination, seeking to control, rather than release, independence in education. We need to start depoliticising schools, so that the often self-interested, short-termist solutions offered up by transient politicians are seen as secondary to the long-term ambitions of the young. This independence in assessment works elsewhere, and in adopting it we may begin to introduce the coherence, stability and rigour that have, for too long, been absent from our children’s education.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.