The first tranche of Labour’s long-awaited housing reforms have arrived. They are a mixed bag. The package is probably a net improvement on the current system, but it is unclear that Labour are making the most of the immense political capital they have for fixing the housing shortage, Britain’s greatest problem.

Here are the key points.

Overall national targets

Overall national targets are going up, from 300,000 to 370,000. Needless to say, this is a good thing. Nobody really thinks that 370,000 will be enough to stabilise prices, let alone bring them down. But it is a substantial step in the right direction: if Labour achieve this, prices will at least rise more slowly.

These targets are also being made more binding. The target system was softened by the Conservatives, including by giving councils more flexibility to use their own methodologies for calculating housing need. These changes have been revoked, making it more likely that local authorities will hit the targets that the Government is announcing.

The local distribution of targets

The biggest problem with the reform programme lies in how these new targets are distributed locally. The national housing target is distributed among local authorities via an algorithm called the ‘Standard Method’. Labour has rewritten that algorithm.

The rewrite has several effects:

- Housing targets in London and other cities have been substantially cut – in the case of London by 20%, and by more in many other areas.

- Housing targets in rural areas have risen considerably. Together with the green belt reforms discussed below, this will have major effects.

- Housing targets in the North have risen greatly. This is a surprising move, generated by a shift from calculating need based on population growth (Northern populations are often flat or declining) to existing housing stock (Northern housing stock is relatively abundant).

The overall effect of the policy seems to have been to shift housing targets away from the areas where housing is most unaffordable and scarcity is most acute. Some rural areas are fairly unaffordable, but none is as unaffordable as London. And the North broadly has good housing affordability, whatever other economic challenges it may face.

.

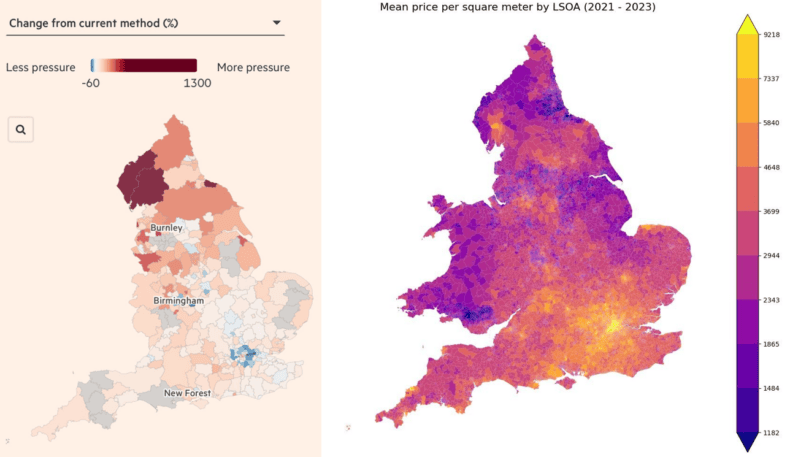

These two maps illustrate the poor match between where the Government is concentrating housebuilding (map from the FT) and where floor space is most scarce. This is a concerning result. Building housing in areas where housing is abundant does not really help with the housing shortage.

.

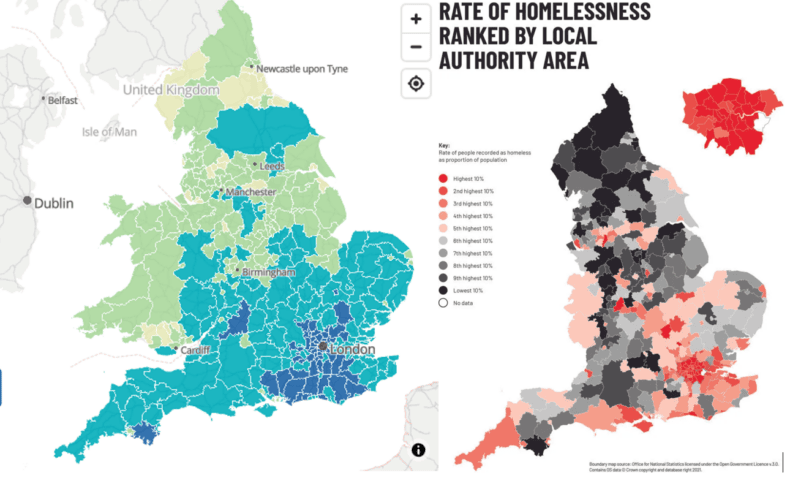

This will have serious human consequences. The map on the left here illustrates housing affordability, showing that unaffordability correlates closely with high floor space prices. The map on the right, from Shelter, illustrates that homelessness correlates fairly closely with this too. By redirecting housebuilding away from high scarcity areas, Labour is blunting the effect of its housebuilding programme on mitigating unaffordability and homelessness.

The green belt

The green belt has long been held sacrosanct in British politics, and any encroachment on it has been intensely contentious. Labour’s proposals on it seem to be genuinely radical. The key paragraph is 142, which would require local authorities to release green belt land if necessary to meet their housing targets. Given that their housing targets are about to go up markedly, this will happen a lot.

There is a qualification, which is that they are not obliged to release green belt if doing so would ‘fundamentally undermine the operation of the green belt across the area of the plan as a whole’. It is a token of the peculiar way in which the planning system works that massively important rules are framed in vague language like this rather than in clear and precise terms: it is not until case law has thrashed out a canonical interpretation of ‘fundamentally undermine the operation’ that we will know exactly what this means. But it seems that it is a fairly permissive constraint, which will allow a great deal of green belt land to be released.

In general, the London green belt tends to be most contentious, because it suppresses by far the most demand. But this change in the rules will apply to all green belts, encompassing a huge and politically diverse part of England. According to the House of Commons Library, 324 of the 543 English Parliamentary seats include at least some green belt land. Approximately half of those now have Labour MPs, often defending small newfound majorities. Magnificent political storm clouds are gathering on the horizon.

Beauty

Many, though not all, of the references to beauty in the National Policy Planning Framework (NPPF) have been purged. The reason given for this is that ‘beauty’ is a vague and subjective concept. This argument would have more force if it were not the case that the NPPF is largely comprised of vague and subjective concepts, like the language about ‘fundamentally undermining operations’ by which the Government totally reformed seven decades of green belt planning.

The NPPF references to beauty are not of great importance in themselves, and it is doubtful that they would have much influence on design without other steps being taken to support them. But purging them is a concerning signal. Making buildings more attractive is one way to make them more acceptable to existing communities. It is odd that a Government facing immense controversy over its housebuilding programme should conspicuously signal lack of interest in one of the ways that this housebuilding could be made less contentious.

Roof extensions

I have a private interest in paragraph 122e of the NPPF, which was introduced in response to a paper I wrote arguing that the Government allow mansard roof extensions on appropriate buildings, provided they emulated the style of mansard roofs in the area at the time that the building was constructed.

I am therefore pleased to see that this rule has not only been retained but expanded, applying under a wider range of circumstances and to a wider range of roof types. It is less heartening, though, to see that the Government has scrapped the rule that extensions should harmonise with the existing building by emulating the local style. We should expect a lot of roof extensions as a result of the revised paragraph, but many of them will be ugly. Once again, one is led to wonder if the Government has found the best way to build and preserve a winning coalition behind its reform programme.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.