A decade ago Britain was experiencing its first run on a bank in a century. On Thursday 13 September, 2007, the BBC reported that Northern Rock had received emergency support from the Bank of England.

What was supposed to be an act of reassurance triggered panic. And by the following morning queues of savers desperate to get their hands on their money had formed outside the bank’s branches. The following Monday, Alistair Darling, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, calmed the panic by guaranteeing deposits at Northern Rock.

At an event to mark the anniversary this week, the former chancellor reflected on the turbulent time and the financial crisis it heralded. He remembered one telephone call in particular: the one from a panicking Chairman of the Royal Bank of Scotland a year or so after the run on Northern Rock.

The Financial Times had reported that morning on a supposedly secret meeting between Britain’s bank chiefs. They were desperately short of cash, none more so than RBS. Now everyone knew it. And when the markets opened, RBS’s share price plummeted.

At the time, it was the biggest bank in the world, with a balance sheet as big as UK GDP. The Chairman told the Chancellor his bank was going to have run out of money by the afternoon and asked: “What are you going to do about it?”

“If it had shut its doors and the cash machines went off,” recalled Darling, “there would have been a run on every bank in Britain and America that afternoon, and frankly right across the world, my guess is.”

Darling was left with no choice but to intervene. It was one of the most nerve-wracking moments of the crisis, he says, and he fears that we are in danger of forgetting quite how close we came to the brink. Just as chastening is the thought that even in a complicated, globalised financial crisis, Britain’s economic fate was largely determined by a few people in Downing Street.

Which is why the current volatile state of British politics – made even more volatile by Boris Johnson’s surprising gambit this weekend – is so worrying.

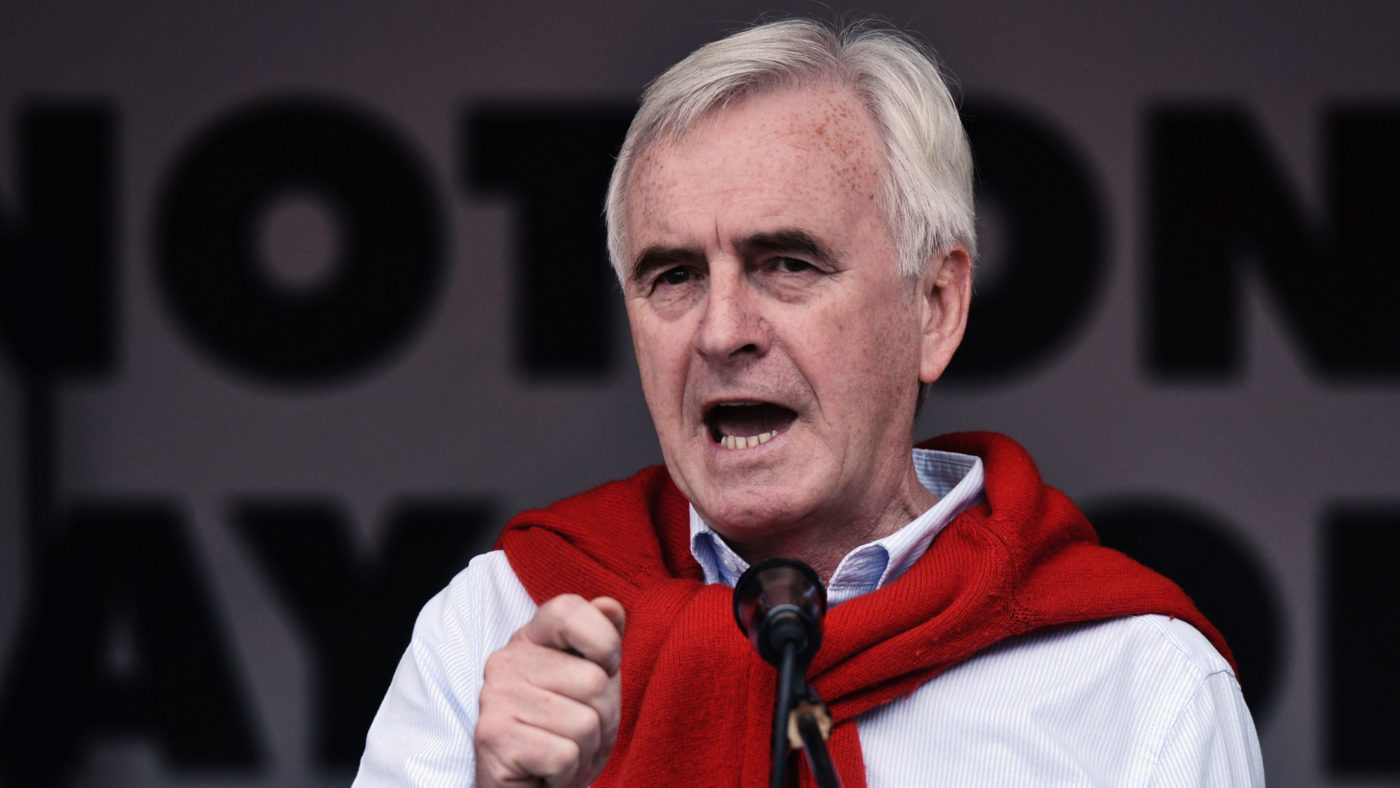

As the Tories barely cling on to power, the man waiting in the wings to replace Philip Hammond in Number 11 is someone who, when asked who were the “most significant” influences on his thought answered: “The fundamental Marxist writers of Marx, Lenin and Trotsky, basically.”

Remember, John McDonnell welcomed the crash: “I’m a Marxist,” he declared, proudly. “This is a classic crisis of the economy, a classic capitalist crisis. I’ve been waiting for this for a generation.”

What if something as serious as the financial crisis were to happen again? Who do you want answering the call from the next panicked chairmen? Not someone delighting in the thought of the impending chaos. Not someone giddy at the thought of angry people on the streets looking for directions to the house of whoever is to blame.

John McDonnell isn’t just anti-capitalist. To put it bluntly: it is unclear if he believes in parliamentary democracy. In 2013, he said that system “doesn’t work for us”. And it is during inflection points, such as the financial crisis, that his intellectual heroes say is the time to strike. Who knows what Corbyn and McDonnell would do were such an opportunity to present itself today.

But one thing is clear: whereas Alistair Darling’s decisions during those tense months in 2007-08 were taken to preserve, as far as was possible, normalcy, John McDonnell would take whatever decision did maximum disruption to the status quo.

It would not be the first time that, in the name of the People, unnecessary suffering was imposed on people. Nor would it be the last.

The popularity of the doctrinaire hard-left is troubling. Not because it demonstrates the inadequacy of the Conservative Party machine (which it does). But because it suggests a deep dissatisfaction with the status quo, to which the Government must find answers soon.

As for the Opposition, moderate Labour MPs should pause to compare McDonnell and Darling. They might marvel at the crowds that McDonnell and his boss attract. They can enthuse about the energising power of their anti-austerity agenda.

Darling was never a showy politician. But he is a reminder of the reputation for competence the Labour Party has always needed if it is to win the lasting affection of the country. And, no matter how encouraged they were by the general election, those Labour MPs who support the Leader of the Opposition and the Shadow Chancellor, are endorsing men who, rather than bring the country back from the brink, would send it over the edge.