Over the past three days, the Republic of Ireland has been counting votes from its snap general election and the results might seem like something of a paradox. The Irish electorate remains clearly disillusioned with its political ‘elite’, but the combined strength of the traditional parties, Fianna Fail (FF) and Fine Gael (FG), means that it will probably get more of the same in government.

Meanwhile, despite an inaccurate exit poll that claimed it would be Ireland’s largest party who would win, the only obvious loser was Sinn Fein. The left-wing, republican party lost a substantial chunk of the anti-establishment vote that it dominated in 2020. This failure can be explained by its incessant involvement in scandals, an unconvincing line on immigration and its all-consuming obsession with pursuing an all-Ireland state.

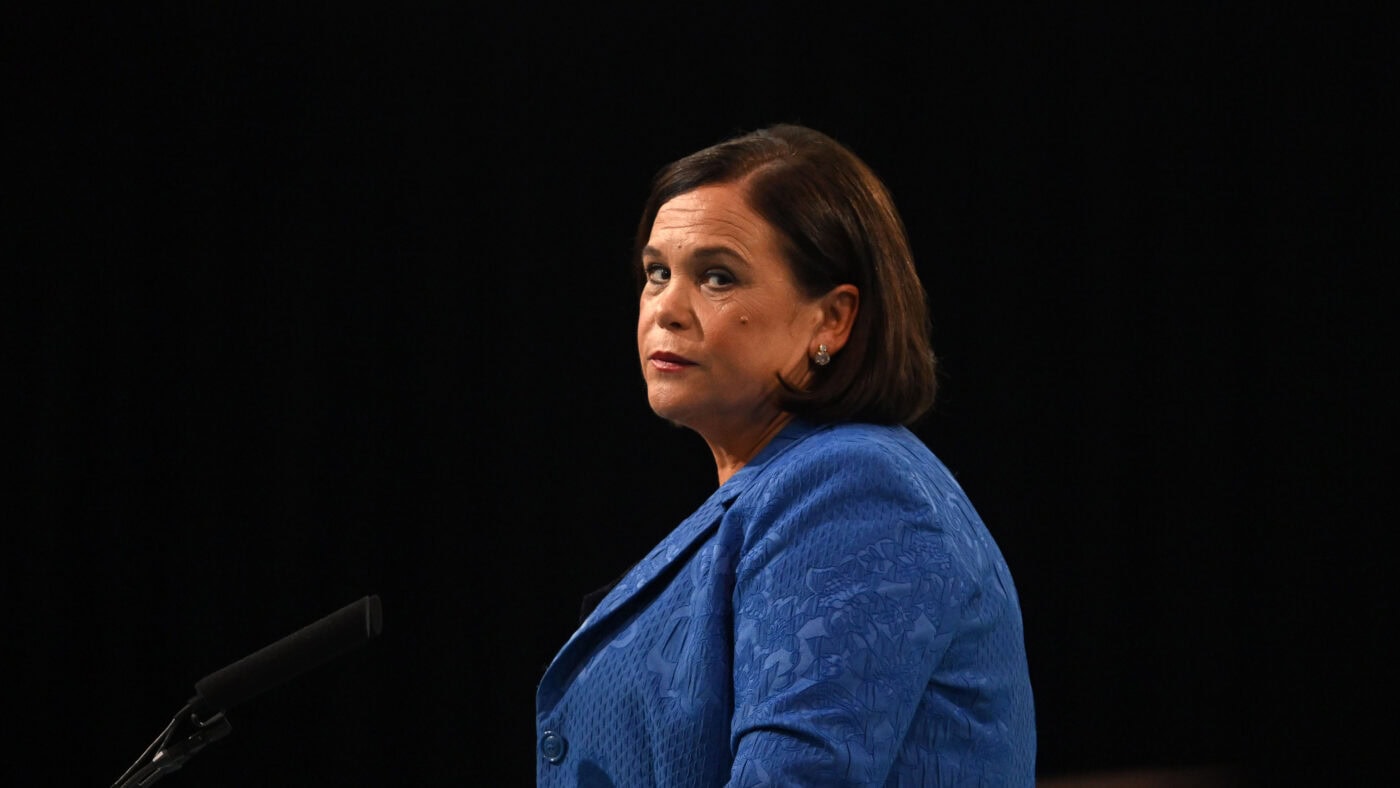

During the campaign, its leader, Mary-Lou McDonald, boasted that by 2030 Sinn Fein would deliver a ‘border poll’ on the Republic taking over Northern Ireland. That claim now looks hopelessly out of touch with the public’s priorities. Indeed, one of Sinn Fein’s political opponents, FG’s minister for public expenditure, Paschal Donohoe, said that it would soon become ‘one of the weakest opposition parties in Europe’, when a new government is formed in Dublin.

This defeat was particularly humiliating because after the 2020 election, many commentators predicted that ‘the Shinners’ would inevitably lead the next Irish administration. At that contest, Sinn Fein won the popular vote for the first time in the modern era.

In fact, last year, before anti-immigration riots swept Dublin, the party’s support was running at 37%, according to opinion polls. It seemed that Mary-Lou McDonald could look forward to becoming the next Taoiseach (Irish prime minister). Instead, she will now have to explain to activists how she managed to lose almost half of Sinn Fein’s prospective voters.

In Friday’s ballot, the party finished on 19% of first preference votes, down 18% from its peak poll numbers, and 5.5% on its 2020 result. That puts Sinn Fein in third place, behind FF (22%) and FG (21%). The two traditional parties were down marginally from their last election performances but remained fairly unscathed in a year when incumbent parties across the western world were punished severely.

The populist vote that Sinn Fein hoped would sweep it to power was spread across a confusing array of independent candidates and small parties. A new movement called Independent Ireland claimed 3.6% of first preferences, but no single group has yet come close to harnessing Irish voters’ disgruntlement with their ‘elites’.

This turn against the establishment was fuelled, in large part, by anger at immigration. Although it has not yet reached British levels, a flood of new arrivals has changed the country drastically in a relatively short period of time. In March, the Taoiseach Leo Varadkar resigned after two bruising referendum defeats on changes to the Irish constitution. In that vote, the government tried to tweak the definition of the family, in line with social changes, and modernise language about a woman’s role in the home, but the public’s rejection of those proposals was widely linked to anti-migrant feeling.

When Simon Harris succeeded Varadkar as Taoiseach and Fine Gael leader, his party’s poll ratings improved and he tried to capitalise on this ‘honeymoon period’ by calling a snap election. That decision has partly backfired, thanks to a fraught exchange with an angry voter, that was compared to Gordon Brown’s ‘bigoted woman’ remarks in 2010. FG was projected to win the popular vote comfortably weeks ago, but eventually lost out to FF, whose leader, Micheal Martin, now has the best chance of becoming premier for a second time.

FF and FG are bitter rivals and they have dominated the Republic’s politics (and its government) throughout the state’s existence. Since 2020, though, they have been locked in coalition government, motivated chiefly by their shared determination to keep Sinn Fein out of power.

After this election, the Republic is likely to see more of the same. There remains a sense, though, that the country is ill at ease. Its parliament, the Dail, will include a strengthened faction of independents and populists, almost as big as the larger parties. Many commentators have hailed Ireland’s economic success, but its model for attracting investment from US multinationals is about to come under unprecedented pressure from the Trump administration in Washington. And the Irish political class still seems out of touch with the public’s views on issues like migration and housing.

For Britain, the outcome of this election means that the next government in Dublin is highly unlikely to contain hostile Sinn Fein ministers or even worse, a Sinn Fein Taoiseach. The party’s campaign for a poll on a ‘united Ireland’ has stalled, for the time being at least.

At the Westminster election earlier this year, unionism restored its lead over Irish nationalism in Northern Ireland. Now, south of the border, this result confirmed that voters simply care far more about other things.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.