As the brilliant Thomas Sowell articulates, economists pride themselves, and rightfully so, on studying ‘the consequences of economic decisions . . . in terms of the incentives they create, rather than simply the goals they pursue. This means that consequences matter more than intentions – and not just the immediate consequences, but also the long run repercussions.’

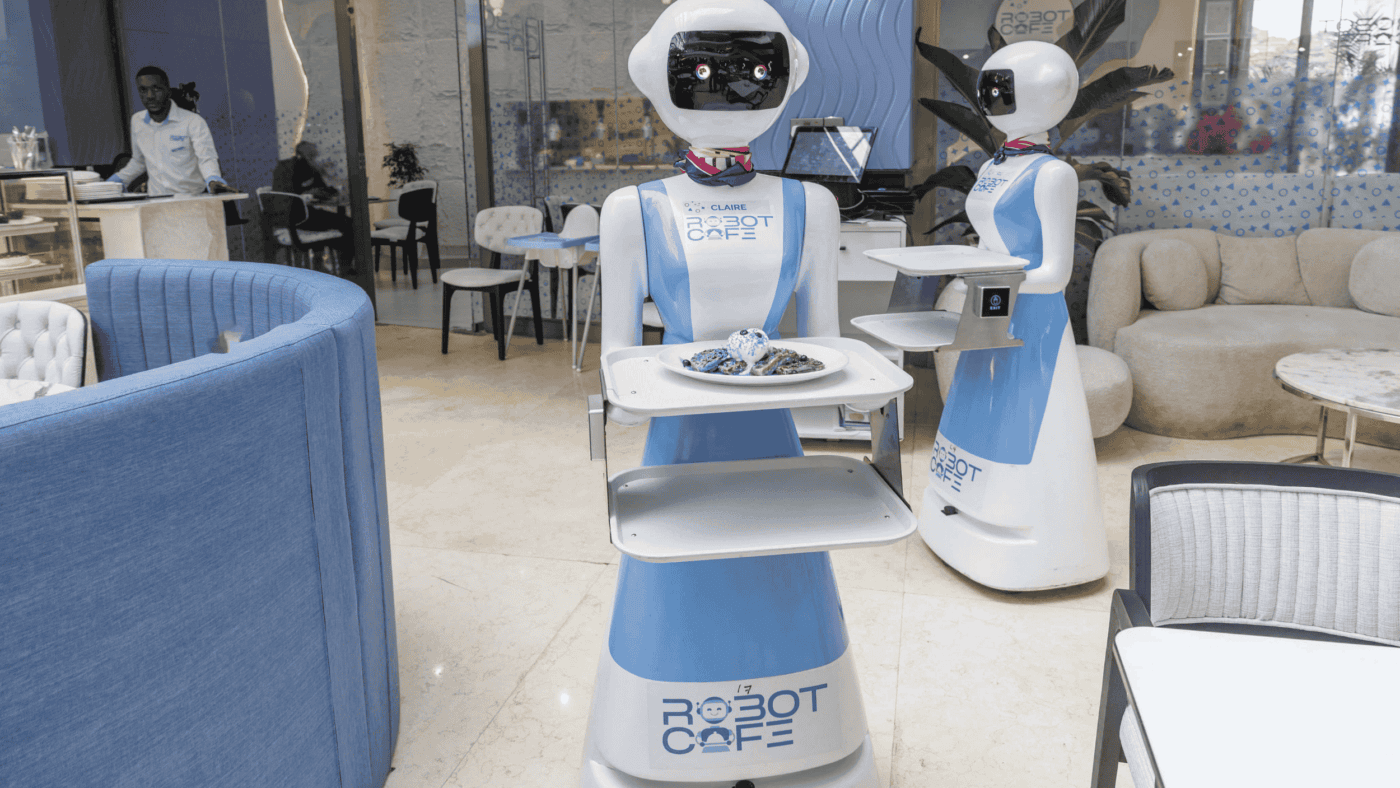

The mantra in economics is ‘Incentives matter!’ And it’s true. Restaurateurs respond to increases in the minimum wage by adopting automated ordering systems. But economists tend to treat this mantra as akin to a basic cause-and-effect principle in natural science. Like Sowell, we may say it is not a matter of opinion that employers respond to rising wages by automating labour services, just as it’s not a matter of opinion that when an alkali metal contacts water, it causes an energetic explosion. But in an important way the restaurateur’s decision to automate in the face of increasing labour costs is not akin to a chemical reaction. The two phenomena are of distinct categories. The restaurateur’s decision exhibits intelligent action; the chemical reaction does not.

Both the restaurateur’s decision and the chemical reaction are intelligible. Chemists can use ultrafast photography to understand the generation of heat and electron transfer when an alkali metal contacts water. And economists can use the principle ‘Incentives matter!’ to understand why restaurateurs substitute physical capital for labour when wages increase. But neither of these intelligible explanations are themselves intelligent.

The categorical distinction is between understanding something as intelligent human action and understanding it as not. The principle ‘Incentives matter!’ doesn’t make the restaurateur’s decision intelligible in terms of why a human being does what a human being does. A human being understands the meaning of another’s action as purposefully chosen by someone who feels, thinks, knows and wants something to happen. Such feeling, thinking, knowing and wanting cannot be reduced to something else. Understanding intelligent human action cannot be reduced to an understanding of something that is not intelligent action itself. Thus, if we are to understand intelligent human action in economics, it cannot come from something, say a maxim or a model, that is not about intelligent action itself.

‘Incentives matter!’ makes economic decisions intelligible, but it does not explain an economic event in terms of intelligent human action. It’s devoid of the stuff that human purposes and relationships are made of – it lacks fuzzy unmeasurable feelings, or what David Hume and Adam Smith call ‘moral sentiments’.

In 1933, the Oxford philosopher Samuel Alexander published a book attempting to explain the nature of value, beginning with the special cases of three supreme values: beauty, truth and moral goodness. With the substitution of ‘economics’ for ‘morals’ and ‘morality’, his description of the problem for moral goodness could serve here:

In [economics] . . . we are concerned with the passions of men, with their desires for material (or it may be immaterial) objects, and the problem which [economics] has to solve is fitting the satisfaction of these passions, both as within the individual himself, and as between individual and individual. Now, our desires and wills are directed to some object external to us, in the sense that it is not yet ours, and in general, as with food, clothing, sex, office, riches and the like, the objects are physical material foreign to us which we make our own. And [economics] may from one point of view be treated as adjustment in practice to our surroundings. Yet these surroundings, when they are external nature, are but secondary to the desires, or rather the wills, which are bent on attaining them.

Alexander is saying that there is a problem as people with strong feelings pursue their desires. How does everyone do this at the same time, particularly when we have different ends? How do we adjust our actions to others as we all seek to acquire material and immaterial objects? Morality, Alexander says, and economics, I say, is about adjusting our actions to fit with everyone else’s actions in the everyday business of life. We may be interested in attaining things for ourselves, but what concerns us is how we go about satisfying our desires. Does the direction of our motives fit with others’ pursuits, or does it come into conflict?

Economics and morality are, in an important way, two sides of the same coin that is human action. The difference is that economics focuses on the outcomes of such adjustments – the costs and benefits – and morality on the origins of such adjustments – the good direction of our motives or wills. In that light, Sowell is saying that we cannot ignore the actual outcomes of such adjustments. Roger that. Let’s take care to do that. I am saying we also cannot ignore the origins of such adjustments, particularly if we want to explain human conduct in the adjustments of life with economic consequences.

This essay is adapted from Bart Wilson’s book, ‘Meaningful Economics: Making the Science of Prosperity More Human’, published by Oxford University Press and available on Kindle here.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.