The Government wants a new deal with Brussels. A ‘very ambitious’ Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) Agreement (otherwise known as a ‘veterinary agreement’) with the EU to smooth the flow of food in both directions. The prize makes sense – getting away from the need for paperwork, certificates and SPS checks at Border Control Posts (BCP) would be a relief to importers and exporters. But is it going to work, and is it worth it anyway? Could we do better with a much more limited deal and unilateral action to encourage trade?

Most trade experts, and indeed the Chief Vet, have commented they expect negotiations to take years. The EU are likely to demand ‘dynamic alignment’ in return; a commitment by the UK to abide not only with current EU regulations, but adopt new regulations as they are passed in future.

There is no doubt that the introduction of controls by the EU created short term disruption and longer term costs for UK food exporters. The previous government tried to get an SPS deal during the original negotiations, hoping that the large EU trade surplus in food would encourage flexibility. But legalism and the importance of stressing the downside of Brexit to the UK outweighed any impact on EU exporters or consumers.

The UK delayed the introduction of many inbound controls. Customs and VAT checks, essential for fiscal reasons, were introduced promptly. But SPS and Safety and Security (S&S) checks have still not been fully introduced. The delays were justified by the wish to avoid economic disruption during the pandemic, supply chain problems and the cost of living crisis. Controls are supposed to be finalised in October, though it remains to be seen if the government will still want to do this, except perhaps as a bargaining tool with Brussels.

Even the scaled down check regime proposed in the UK Government’s Border Target Operating Model (TOM) costs about £500m pa more than the position before EU exit, with S&S declarations adding over £100m pa on the import side alone (and a similar amount for exporters), with SPS controls adding around an additional £400m to the cost of imports.

The ‘biosecurity’ arguments for these checks is highly dubious. Food has been flowing freely for 40 years. At no point during the referendum did the Food Standards Agency (FSA) suggest EU trade posed a biosecurity risk, which would certainly have caused a stir. Once Brexit had happened, however, demands for the full checks were shrill. But now apparently a veterinary agreement will negate the need for them, with nothing changing except for restored access to some EU databases.

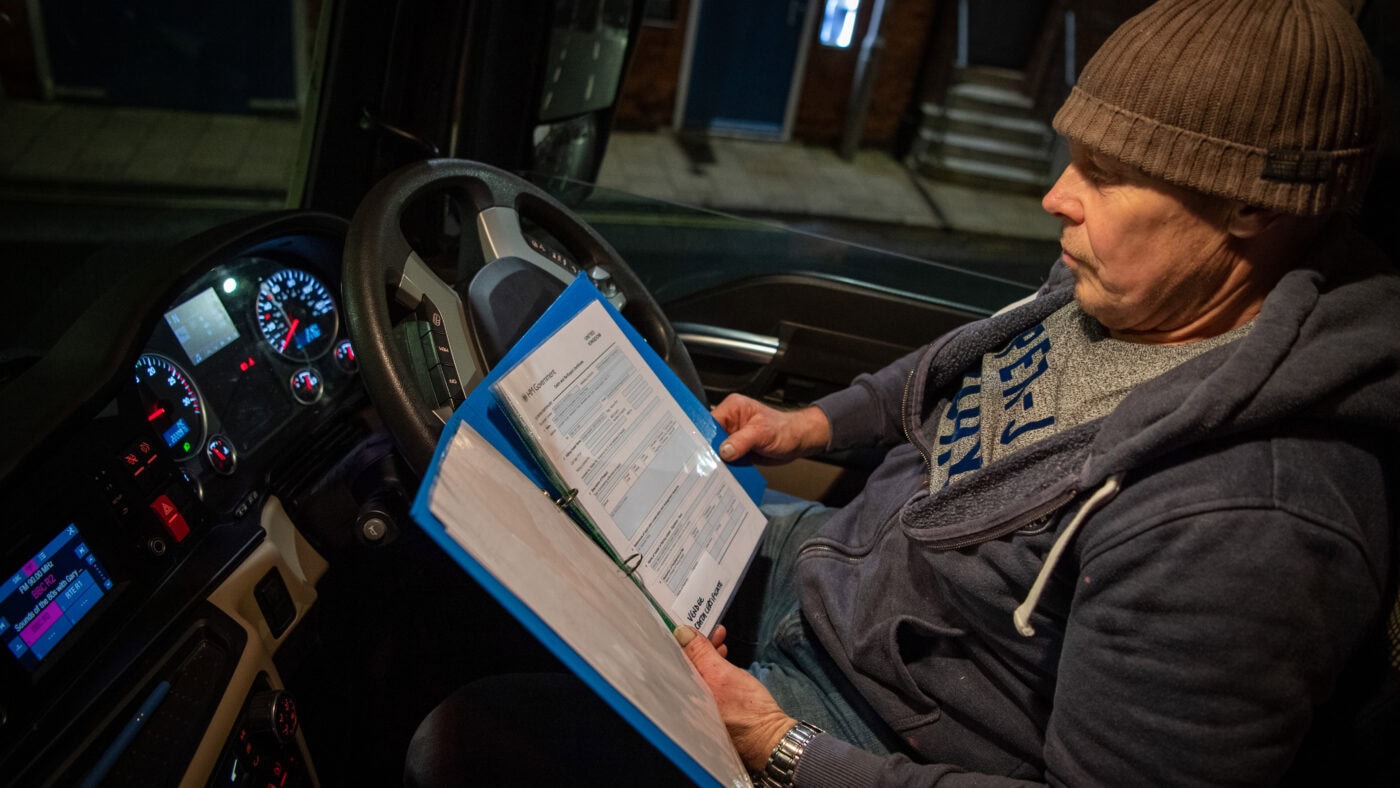

There isn’t much point to the checks. They involve additional paperwork and the provision of vet certificates – but the vet in practice just looks at consignments of prepacked cheese and signs the certificate. There is no testing involved, and yet every single consignment from the same place needs a new certificate, at the estimated cost of at least £150m pa.

On the UK side, the running costs of the new BCP for the short straits alone will require a flat charge of £10 to £29 for every consignment passing through, which will be passed on to consumers. A tiny fraction will be checked, but the value of checks is doubtful. Defra and the FSA talk about the pressing need to tackle biosecurity threats like foot and mouth. But the BCP checks are hardly relevant to that. Of the two foot and mouth outbreaks we have seen in the UK, one probably came from illegally imported produce, the other was a leak from Defra’s own laboratory.

The S&S regime is equally odd. It’s basically just another set of paperwork which border enforcement agencies review and which may potentially give them additional leads. The Home Office in the TOM claimed the introduction of these checks would lead to very significant increases in seizures of drugs, guns and cash. The information won’t lead to results on its own – it will need processing and ultimately physical examination. Given no increase in Border Force resources, the Home Office claims are only logically possible if you believe that trade from the EU is actually on average higher risk than that from the rest of the world. Again, this would be sensational news not previously revealed during the referendum campaign.

An alternative approach would be to scrap controls on EU food imports into the UK unilaterally (as well as from other countries in which we have high confidence), and to negotiate a much more limited deal with the EU to abolish S&S declarations on all trade. This would get most of the benefits for the UK consumer of a veterinary deal, relieve a big administrative burden on trade – up to £250m pa – in the form of S&S declarations, and leave the UK free to diverge from EU regulations.

This obviously helps importers, not exporters. But if we go ahead with checks, we risk imposing pointless costs on hard pressed consumers for years as negotiations drag on. If we eventually get a deal, we will be able to abolish our own checks and free exporters from theirs too. But at what cost? We will certainly no longer be able to relax checks on imports from elsewhere. We may not be able to implement government policies like the banning of cruel products like foie gras. Or to press ahead with potentially transformative technologies like gene editing, the Bill allowing which Labour supported in 2023.

It might stick in the throat to welcome EU trade into the country while our own gets caught in bureaucratic processes going in the other direction. But ultimately the EU is only harming its own consumers, and there is no need to copy them for mercantilist reasons.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.