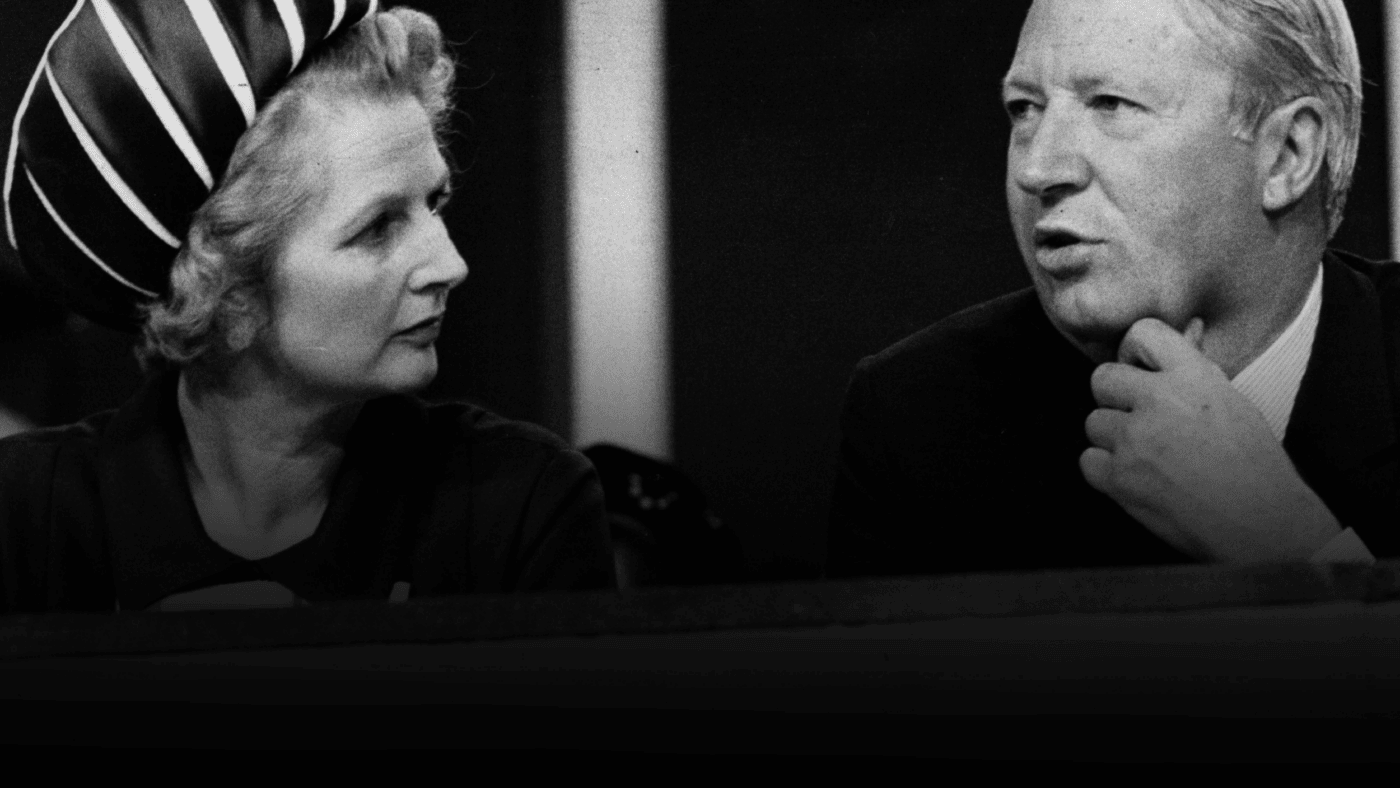

It’s fifty years since Margaret Thatcher became leader of the Conservatives. Over the decade and a half in which she led the party, Thatcher would remake conservatism, the state and the economy in her own image. Yet she may never have become leader, and the word ‘Thatcherism’ may never have crossed anybody’s lips, had it not been for the singular arrogance of one man: her predecessor, Edward Heath.

Heath was a consequential leader of the Tory tribe. He was the first grammar school boy to lead the Conservatives, filling the shoes of a succession of old Etonians who came before him. And as prime minister, he took Britain into Europe, something the country is still wrestling with the consequences of doing (and undoing) five decades later. Love him or loathe him, Heath mattered. But for all his accomplishments, he was not an electorally successful leader.

Heath’s first clash with Labour’s Harold Wilson, in 1966, saw Labour returned with a landslide majority. He turned the tables four years later and won a reasonable majority, but when he gambled it on a snap election in February 1974, Labour got back in – albeit with fewer votes than the Conservatives. In October 1974, the country was asked again and confirmed Heath’s defeat, this time in votes and seats.

Heath had fought four elections and lost three of them. It’s unimaginable today that a Conservative leader with such an unenviable record would try and stay in post; ever since, every election defeat has been followed by the hasty exit of the leader. But not Heath. He believed that only he could lead the Conservative party through the trials ahead and nobody, not the Chairman of the 1922 Committee, nor even his closest friends in politics, could convince him otherwise.

Such intransigence was not out of character. Since being elected Tory leader in 1965, Heath had become distant and aloof from the MPs whose support he needed to command. As one of Heath’s biographers, John Campbell, so crushingly put it: ‘Tory MPs who had been willing to put up with Heath’s remoteness and rudeness so long as he was Prime Minister felt no obligation of personal loyalty to such a graceless boor when he began to look like a loser.’ Ouch.

Today, the impasse would be solved with a confidence vote. But at the time there was no way of removing a Tory leader; they had a ‘freehold’ on their role in the party. Amid a growing rebellion, Heath eventually agreed to a rule change to enable a challenge to his leadership, after which two people were brave enough to try and knock him off his perch. One was the Tory traditionalist Sir Hugh Fraser, who had neither an obvious support base nor a campaign operation. The other was Margaret Thatcher, the former Secretary of State for Education.

Thatcher wasn’t the biggest name in the party nor was she widely seen as an alternative leader. Nevertheless, it was to her that the anti-Heathites decided they must rally if they were to remove their seemingly immovable leader. And so, as Tory MPs voted in only the second ever Conservative leadership contest, Thatcher acted as the conduit for voting ‘no confidence’ in Heath’s leadership. If you want rid of Heath, her campaign manager Airey Neave would tell MPs, you have to vote for Thatcher. There was no alternative.

Team Thatcher’s appeal to tactical voting didn’t just help dislodge Heath, it earned her a lead on the first ballot. She attracted 130 votes, with 116 for Heath and just 16 for Fraser. It was a humiliation for Heath, who finally saw the writing on the wall and resigned. He turned the air blue as he told Bernard Weatherill, the future Speaker of the House of Commons, that the Tory party contained ‘shits, bloody shits and fucking shits.’

While the job of removing Heath was complete, the leadership contest was not. There would be a second round in which alternative candidates. including some of Heath’s former supporters, could enter the fray. Several did, most notably Willie Whitelaw. But the Thatcher juggernaut, given inflated support by MPs who wanted rid of Heath but did not yet want her, had the momentum required to win again. In the second round, Thatcher polled 146 MPs, an absolute majority. She had seized the Tory leadership.

Given the epoch-defining consequences of Thatcher and Thatcherism, it feels absurd that she may not have become Tory leader and prime minister. Yet had Heath succumbed to the pressure earlier and resigned with his dignity (mostly) intact, the perfect circumstances for her to rise to the top of the Tories would not have existed. After 1975, Heath would spend the rest of his long political career on the backbenches, irreconciled to the changes Thatcher made to the party and country he once led. If only he had known what was to come, he might have thought twice about helping her on her way.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.