Even in the gamesworld of fantasy conflicts, a Dutch-Turkish War would seem improbably over-the-top. The suddenness with which the war of words between Holland and Turkey broke out over the weekend was, however, not quite the freak event many took it for.

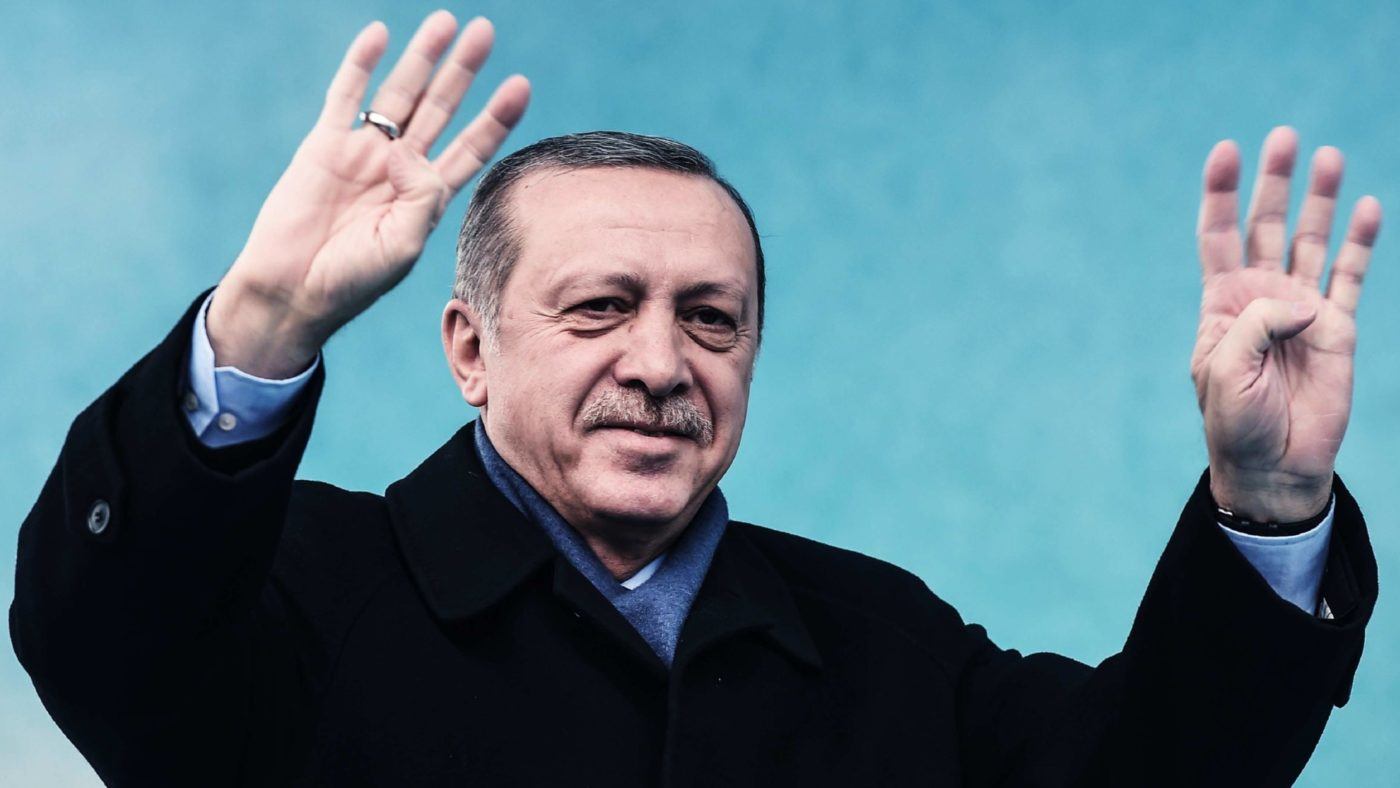

It brought into the open the rumbling resentments between Turkey as the eternal suitor for EU admission and the Dutch as the archetypical liberal Europeans who find their Muslim suitors just a bit too provincial and religious. But it was the conscious decision of the Turkish president to stir the pot with inflammatory rhetoric which sent the political temperature soaring.

Polarising the electorate at home by standing up staunchly as Turkey’s champion abroad has played well for him during his 15 years in power. Presenting his internal rivals as soft-touches for foreign powers who want to take advantage of Turkey has resonated with about half the population – enough to win a majority in parliamentary elections.

But now Erdogan is facing an unusually close battle to get the Turkish people to back a new constitution. He needs 50 per cent of the vote to ensure changes which will vastly enhance his powers and cut back parliamentary scrutiny.

Winning the referendum poses a bigger challenge for Erdogan than shooing his AK Party to a parliamentary majority. The AKP has been able to secure a clear majority with votes in the low 40 per cent, but a referendum requires an absolute majority. The splits in the opposition vote which have helped Erdogan to parliamentary majorities are much less deep over the referendum.

Although the ultra-nationalist MHP’s MPs voted for the constitutional changes because they want an authoritarian republic, regardless of who exercises the presidential power, the risk is that even some of their voters will reject the president as much as his project, as the referendum focuses more and more on his personality.

Erdogan’s argument focuses on himself as the guarantor of Turkish security in a tough neighbourhood. Turkey, he says, needs a strongman as president. But his critics note that terrorism, cross-border problems with Syria and Iraq plus economic difficulties have worsened since he became president in 2014.

The situation, in fact, cries out for a firm hand on the tiller; Erdogan’s mercurial political personality means that his authoritarian way of running Turkey causes the ship of state to sway dramatically from one course to another.

At any given moment, Erdogan and his government are in full cry against an enemy, but the name of the national foe can change overnight. The president thrives on unpredictability but his kaleidoscopic choice of enemies leaves Turks, their neighbours and partners in Nato breathless.

Last Friday, Erdogan was in Russia beaming with pleasure as Vladimir Putin talked up cooperation on energy, tourism and security between their two countries. It was if the the shooting down of a Russian fighter on the Syrian-Turkish border in 2015 and the subsequent diplomatic crisis had never taken place. Ankara and Moscow are best buddies again, cooperating over Syria and cocking a snook at Turkey’s Nato allies.

The paint was barely dry on the mended fences with the Kremlin when Erdogan launched a verbal war against Holland at the weekend which drew in key EU members such as Germany, Austria and Denmark.

The Netherlands is a small but key component of the Western alliance. Its high-minded politicians and journalists routinely berate the authoritarianism of the Turkish president, along with many other less-than-perfect regimes around the world. It also happens that the Netherlands is the home of hundreds of thousands of Turkish and Kurdish migrants. Indeed, immigration is a sensitive issue for the Dutch government as it tries to fend off the challenge of the Islamophobic Geert Wilders in Wednesday’s general election.

Erdogan sensed that the run-up to the tense Dutch election would give him an ideal opportunity to profile himself and Turkey as the victim of Euro-double-standards. Sending Turkish cabinet ministers to try to address crowds in Rotterdam was a red rag to the liberal Dutch government.

Chants of “Allah Akhbar” by the disappointed resident Turks who clashed with the riot police after the expulsion of Erdogan’s head-scarfed family affairs minister were suitably headline-grabbing. Dutch Islamophobes said “case closed”, while Erdogan’s supporters saw the water-cannon and dogs used by the police as proof of Turkish victimisation.

Erdogan’s threats of retaliation might ring hollow, however, because Turkey cannot do much to harm Holland’s economy. The Hague has far more levers at its disposal to demonstrate displeasure with Ankara than the other way around. Official warnings to Dutch tourists to avoid crowded places and identifying as Dutch are a hardly likely to encourage an upturn in tourism to Turkey which has already been hit hard by the ISIS terrorist attacks and the coup last July.

But Erdogan might “go nuclear”; he might open up his borders with the EU and release the pent-up migrant stream which Ankara has staunched for the last eighteen months in return for a generous subsidy from Brussels.

Cutting off his nose to spite his face has been a short-term gambit used by Erdogan to rally nationalist support. His falling out with Russia was a good example. Making up in Moscow has meant rowing with the EU.

Even though the president feeds off confrontation, however, Turkey’s economy cannot afford it for much longer. Inflation is now 12 per cent and rising. The balance of payments is dipping further into the red as energy costs rise and tourism shrinks.

Servicing debts both state and private which are dollar or euro denominated is getting tougher all the time as the lira loses value. The fight against the Kurds in the South-East and in Syria where 60 Turkish soldiers have been killed since the start of the year shows no sign of ending – and the costs are soaring.

Erdogan’s calculation that Turks will rally around him if Europeans decry him will probably carry him over the 50 per cent hurdle in April’s referendum. But as the economy falters further and more Turks die fighting terrorism, separatism and allies of the West in Syria, popular support could evaporate.

Then the likelihood is Erdogan will conjure up another crisis.

And sooner or later he will pick a fight which spirals out of control. If someone hits back, then Turkey’s ultra-sensitive geopolitical position and its fragile economy could result in more than simply verbal fireworks.

That won’t only be a problem for Erdogan and Turkey. With the deep divisions between America and its European allies on the one hand and Russia and Iran on the other means that any attempts to manage Erdogan’s next spat could test everyone’s crisis-management skills.

Meanwhile, Erdogan will carry on playing with fire. Even after the referendum. Then, the greatest fear must be that if he has lost the referendum, he will looking for something to distract the Turks from his defeat at the polling booth.