Isn’t The Guardian just delightful at times? Take this recent piece, seemingly about fishing. Look beneath the surface, and the reporting actually manages to both diss the Left’s new favourite economist Mariana Mazzucato, and also show that central, let alone state, planning isn’t how productivity and economic growth happen. Of course, being The Guardian, they’ve not realised it, but that’s all part of the delight.

The piece reveals that seafood chef Mitch Tonks found that it was difficult to get access to fresh fish during lockdown. Boats were docking and couldn’t sell, consumers were bereft and so on. So, with the help of the internet and smartphones, he created an online market. This approach turns out to be part of a wider trend, which has continued to transform the fishing trade. Catches can now be recorded at sea, put up for sale before reaching land and even bought before they reach shore as well. Profits are up, spoilage and wastage down and consumers are gaining quite possibly better fish to boot.

This is all known as pure economic gain. We’ve pulled the inefficiencies out of the system, and thereby reduced the overall costs. Those gains are then shared in some manner between all those involved – even fish wholesalers who now get to do something else for a living other than getting up at 4am to stare at dead piscines. We’ve done this by adopting a new technology.

Note something about technology when used in this economic sense. It doesn’t – or doesn’t only – mean the electronics, the chips or the RF towers. It really means ‘a new way of doing it’. That’s what a technology is – a way of doing something. Certainly, the chips and towers and so on allow this new way, but the key word is ‘allow’. This will be important later.

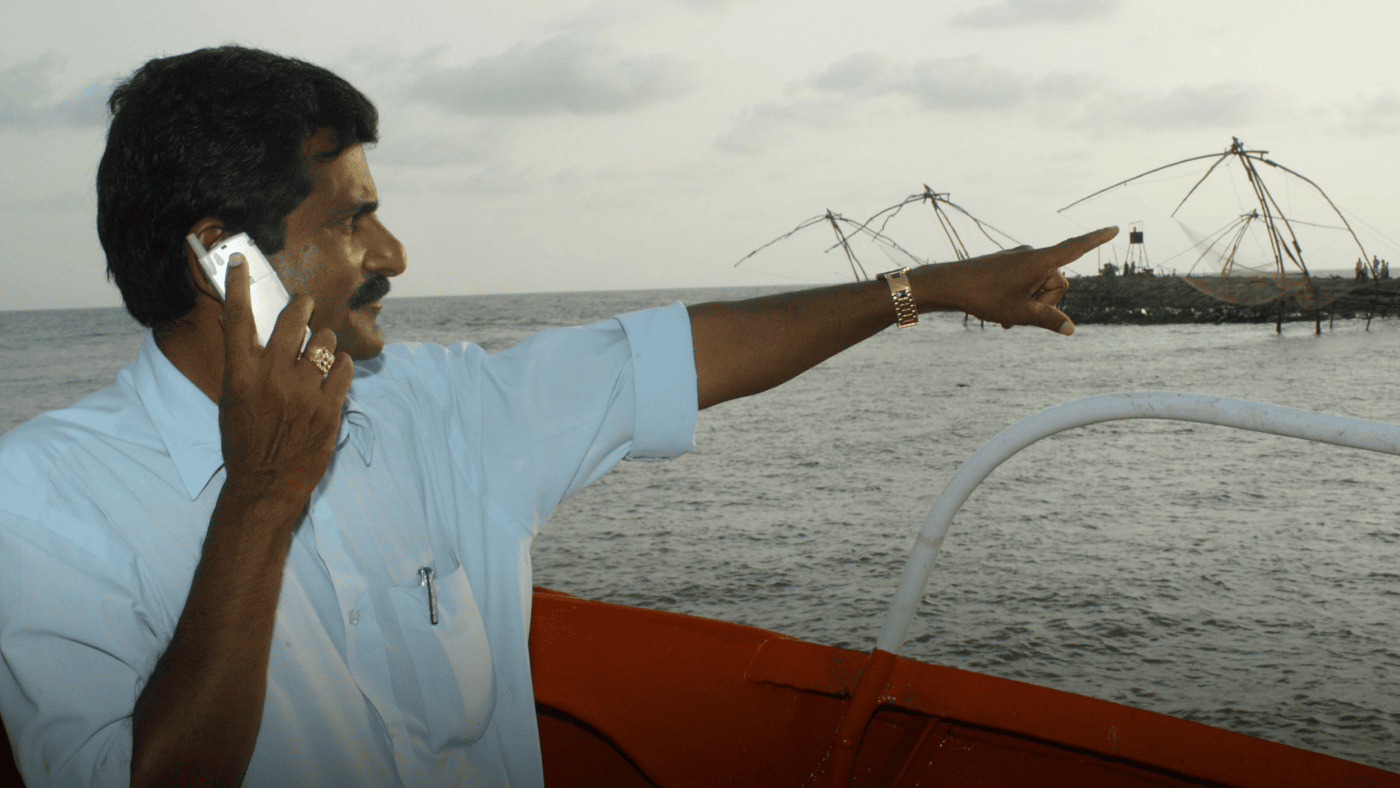

To those of us who follow these things, one small joy of this example is that it echoes an earlier piece of research. What is the economic effect of mobile phones? The seminal study was done on sardine fisheries off Kerala. Radios (not little transistor jobs, but ones that can be talked upon) were too expensive for the local fishermen. So, communication at sea didn’t happen unless within hailing distance. Then came mobile phones, with coverage good enough to cover those inshore fishing grounds. At which point cooperation and information abounded.

Firstly, it was now possible, when a boat encountered a shoal with more fish than it could manage alone, to fire up a mobile phone and call friends over to share the catch. Secondly, there are a number of ports along the coast, and before mobile phones it wasn’t possible to know who had already landed a catch at which port. Prices therefore varied wildly between ports and days. But once committed to landing at one, the fishermen were committed. Fresh sardines don’t stay fresh all that long off Kerala. Thanks to the phones, it’s now possible to look at the catch, phone around and find out which port has the best prices – fewer previous catches landed – and so maximise income.

The study found the overall effect was that for the fishermen costs fell – largely less fuel and labour time. Incomes rose as they landed into gluts less often. Prices also fell for consumers overall – fewer gluts, yes, but also fewer shortages. Wastage dropped. Profits rose even as consumer prices fell. A pure economic gain. Just because communications allowed it all to happen.

We can go back one stage further, too. Back when mobiles were still a pretty neat idea, it was shown that an increase of 10% – as a share of the population – in mobile phone ownership increased GDP by 0.5%. This was in countries unblessed by already having a landline network that both had a wide distribution and also actually worked – so, most places outside the Global North. This is also not 0.5% on the GDP growth rate, this is growth of fully 0.5% of GDP. For each tenth of the population that had mobiles, another 0.5% each year.

Which raises the possibility that a fair slice – though certainly not all, I’d have to be in my cups to argue that – of Global South economic growth this past few decades might not be due to globalisation at all, but simply better comms.

To understand why, the example is often given of a man with a field of weeds he wants clearing. Without a comms network, he has no way of knowing there’s a goatherder three miles away looking for forage. With one, the goats get to eat, the field gets cleared and some exchange of a leg or three of juicy young kid no doubt gets passed over as well.

Communications allow market transactions to complete. Since economic value is formed in transactions and is not formed in not-transacting, more of them completing is economic growth. This is not a logically difficult contention.

But now we need to consider central planning. This is the contention that the government – or someone with power at the centre, which is largely the same thing – can decide what should be done and then make sure it is. But there’s no way that a government is going to set up an online fisheries market in Cornwall. Nor Kerala – and goat forage is right out. This simply isn’t the right level of detail for people on £80k a year and fat pensions, even if they could – and as Hayek proved, they can’t – get the information. But this is also the level at which economic growth really happens.

It isn’t – it just isn’t – some grand new factory that the Minister gets to cut the red ribbon for. Economic growth is that slow and ongoing process of squeezing costs and inefficiencies out of things being done. Sometimes it’s new things – goat grazing! – and sometimes it’s old things done better, like sardine fishing. But this is what productivity increases are, just sating human desires that little bit better along the way. Further, to complete the point, increased productivity is what brings economic growth: when we are more productive with our resources, we are squeezing more value out of what we have – and as a result we have more to enjoy.

Which then brings us to the Mazzucato diss. For not only does she insist upon all that cross-cutting, mission-driven industrial strategy with strict conditionality stuff, she also insists that it’s a horror that the tech companies make a profit. Her early refrain was that government(s) created every technology within an iPhone… so why does Apple get all the profits?

The first and obvious answer is that no government, anywhere, has ever created a smartphone, but Steve Jobs did. Which is the very definition of entrepreneurialism. Taking the bits and bobs lying around – technologies, desires, physical and economic assets – and converting them into something worth more, once converted, than they were unconverted.

But there’s a very much more important point here, and it’s one that the impact of the internet and mobile phones on how we buy and sell fish helps to illustrate. Let’s grant that modern comms – mobile phones, smartphones and the internet – all did have at least some starting points in government funding. But it is irrational to care in the slightest who gains the profits from building and selling the devices that bring them into mass-market use. Because the profits seen to accrue for doing so, while substantial, aren’t of any great interest when set aside the extraordinary gains in value created by the use of these new devices. That 0.5% on GDP growth in every poor country. There’s more poverty reduction in that than any confiscation we might make of Apple’s profits.

In fact, even this was tested. Some countries did indeed decide that these new mobile phones should be owned by the local government. Monopolies were insisted on, to ensure that the value was captured. Others went hell for leather with multiple providers, and didn’t care about the profits those firms made. The second model got more phones into more hands more quickly. And so, obviously enough, brought about more of those 0.5% increases in GDP.

It’s even possible to muse that the tax take on economic growth due to increased take up of mobile phones is likely higher than the profits that would be made by a state telecoms provider.

This is, to my mind, the Mazzucato mistake. We just shouldn’t care who owns telecoms, tech or IP. Economic growth doesn’t come from these things at all. Economic growth comes from people using these things to do stuff. That value isn’t captured by state ownership or control of the tech – and in the case of mobile phones, it’s positively hindered by it.

Productivity growth, which drives economic growth, is not about who makes or profits from disseminating new technology. It’s about who uses new technology to do new things that add more value. Whining about who gets the profit from making that possible is an irrelevance.

But, you know, The Guardian. I don’t actually mind that their journalists don’t see it. I just wish their readers would grasp this stuff.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.