Building in Britain has gone awry. An inability to lay brick atop brick – whether in power, water, transport or housing – is seen as a key reason for stuttering growth and flatlining productivity. Whether collapsing hospitals, absent reservoirs, axed railways or pylons stuck in development hell, it gives a physical form to a national sense of stasis.

Often, this is illustrated through comparisons with places such as China or the Gulf States. But the more troubling comparison, and the one which should give real cause for alarm, is that with our own past.

We think of the Victorians as the great builders of our history, but the height of construction came in the years around the Second World War. The all-time record for house-building was set in the 1930s. During the war, the Air Ministry laid runways equivalent to 9,000 miles of road. As the Atomic Age began, Britain unveiled the first civil nuclear power station in the world, then built ten more in 15 years. This construction was not only possible within a democracy, but was required to save it.

However, while concrete and steel were reaching to the skies, there was a deepening public unease. Just as Britain had pushed the boundaries of civil engineering, it was also the place where many of the modern ideas of nature and environment had been crafted. And, amidst this frenzy of building, a reaction began to set in.

In 1947 the Town and Country Planning Act was passed, creating a new state-led system of development control. This was not intended to stop building, merely to ensure that the state could steer it within a coherent plan. The state would still build actively, as Labour and Tory governments rolled out the Supergrid, the motorway programme and a 300,000-a-year housebuilding programme.

But as time passed, and building did more to change the character of country or town, disquiet grew. From the late 1960s, successive governments sought to defuse this concern within the planning process. Requirements for public consultation were introduced, and environmental protection measures were given greater strength. And, in the early 1970s, this allowed some of the first big anti-development campaigns to confront big projects such as London’s planned urban motorways – and win.

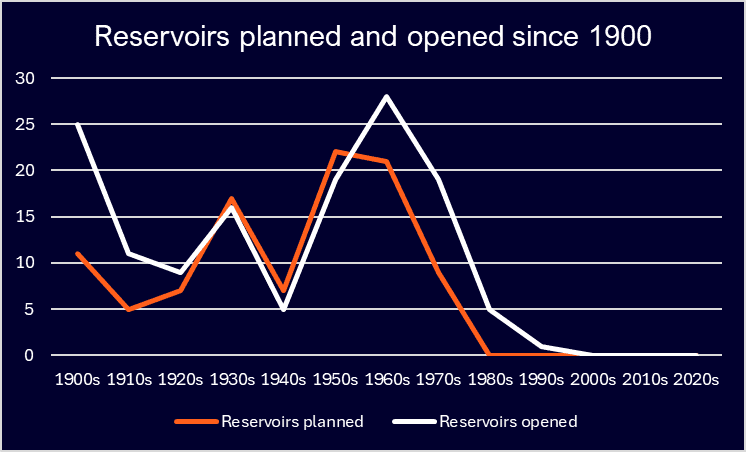

The defenders of peace and quiet had finally tamed building. However, it soon became clear how far the pendulum had swung. Take the example of reservoirs – in the 1960s the water authorities typically gained permission to build two or three reservoirs a year, and completed a similar number. Then came planning inquiries. Carsington Reservoir’s inquiry took 5 years; Roadford took more than 6. No one has submitted a successful planning application for a new reservoir since 1976.

.

This was already a recognised problem by the 1980s. The planning inquiry for the Sizewell B nuclear power station required 340 days of hearings – much of which was a debate about the fundamental merits of nuclear energy. By contrast, the inquiry for the Trawsfynydd nuclear power station in 1957 had taken three days, despite the site being in the heart of Snowdonia National Park. Similar stories were told for motorways, airport terminals and more.

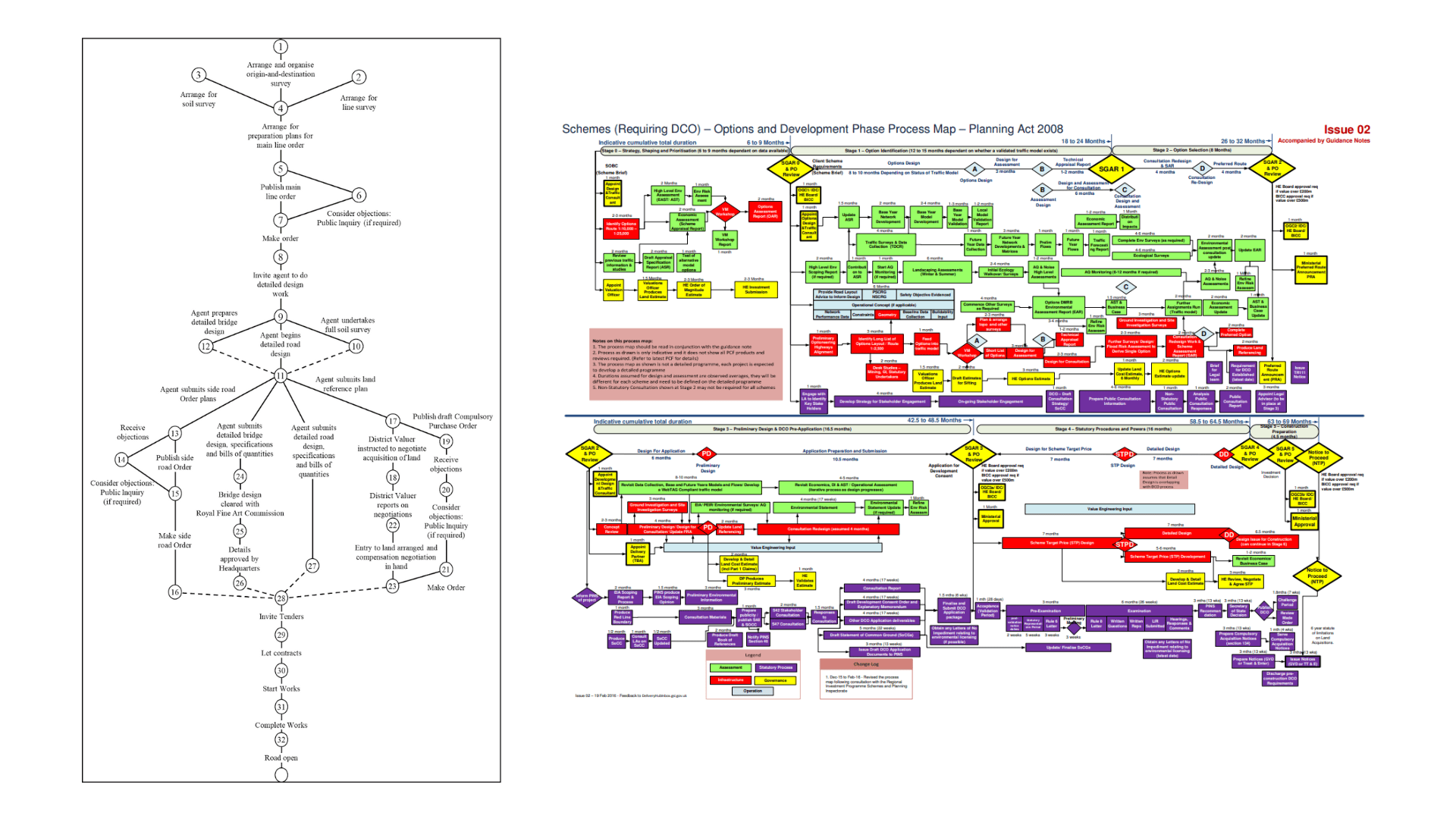

However clear the problem, efforts at reform have proven fruitless. The Planning Act 2008 put time limits on those long planning inquiries, but only by relocating much of the work to an even-longer process of preparation. In parallel, the growing sophistication of environmental science means that old protections are now delivered through far more complex processes of search and mitigation. Couple this with a surge in crowd-funded legal challenges and this ‘reformed’ process can take a decade to conclude.

Highways planning process in 1964 and 2016

Three things stand out in this story. The first is that it happened gradually. There is no single moment when the fast-building system of the 1950s was turned into the stalemate of today. Instead, it was a series of steps, almost every single one of which has seemed reasonable. When protections are brought in to preserve habitats or limit air pollution, this is not contentious; and these are not the frivolities that periodic ‘red tape challenges’ will do away with. Hence, reform is hard.

The second is that the combined impact of all this searching has been so large. Few people would instinctively object to the planning process looking to preserve threatened species. However, with almost 1,000 protected species on the books, the process of showing there will be no impact on a single one of them is considerable. A list of individually reasonable tasks now adds to an unreasonable overall timeframe. For many categories of infrastructure, the time from starting development to starting construction is now greater than the five-year electoral cycle. This means that a government can be elected on a mandate to build, yet have no spade in the ground by the day of the next election. This is no longer a matter of planning, but of democracy.

Lastly – while this sounds like a wicked and insurmountable problem, it is also something that exists entirely within the mind. The slowing down of building has not been because the laws of physics became more onerous, only the laws of man. What we are trapped beneath is a weightless weight.

This may be maddening, but it should give us hope. The fact that Britain does not build is a choice, albeit an unconscious one. In our recent report, we suggest that it ought to be possible to develop simpler projects in one year, rather than five, if we can put the wish for protection on an equal footing to the need for results.

Britain used to be a nation that inspired others by what it could build. With the right reforms, it has a chance to inspire itself.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.