As members of the Liberal Democrats head to Brighton this weekend for their annual Autumn Conference, a question worth bearing in mind as they debate and decide upon party policy is this; “how does this differentiate ourselves from Labour?”

Far from fighting back at the last general election, the Lib Dem share of the vote fell once again. Much of this was due to the party’s failure to give voters a compelling reason to vote for them over their rivals; according to Ipsos MORI, even 2015 Conservative voters were more likely to switch their vote to socialist Labour than to their recent coalition partners. In the end, many local parties had to resort to promoting “tactical voting” websites, in a desperate attempt to gain some kind of support.

Perhaps this is to be expected when so much of the party’s campaigning both pre and post-election has been on areas that are traditionally strong for Labour and have become even more so since the election of Jeremy Corbyn as leader. Take, for example, NHS spending; current Lib Dem policy commits the party to spending £6bn, raised through a 1% increase in income tax, Labour meanwhile promise £7.4bn, funded instead by tax rises on the top 5% of earners. Although you can (rightly) argue that the Labour policy is unrealistic, by that point you’ve already lost the debate; according to YouGov, 39% of voters trust Labour with the NHS, compared to only 4% who trust the Lib Dems.

Rather than trying to do battle on what is solid Labour ground, the Liberal Democrats must instead carve out a niche of their own.

The NHS, homelessness and poverty are important issues. But when Labour look to promise the earth, it’s hard for the Liberal Democrats to compete. Being anti-Brexit alone is not enough, the terminal decline of UKIP since the EU Referendum shows what happens to smaller parties that define themselves by a single, time-limited issue – once the issue is no longer at the forefront of voters’ minds, they return to other parties.

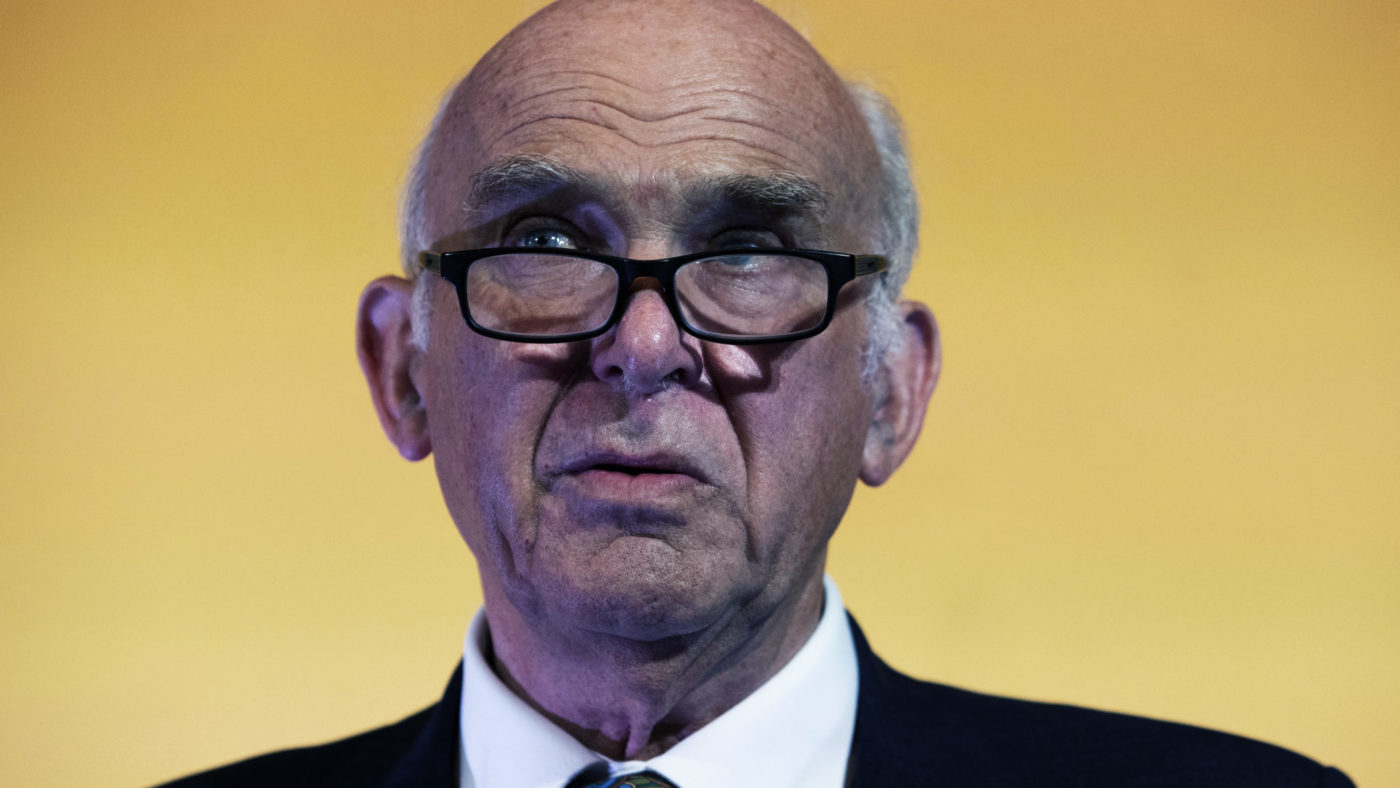

Neither are Vince Cable’s proposed reforms to party membership and elections alone likely to bring success; to engage the wider public, the party must offer an inspiring vision, not simply offer them an opportunity to vote for the party’s leader free of charge. The Liberal Democrats should look to re-brand as the party of enterprise and opportunity; The Conservatives’ commitment to ‘hard-Brexit’ means they can no longer credibly claim to be ‘the party of business’. Equally, the entire Corbyn project is based upon resentment for those who create jobs and prosperity.

This does not mean that the party should embrace the Conservatives’ crony-corporatism – markets must remain competitive if they are to be successful. Nor does it mean that the party should tack rightwards on issues such as immigration, indeed it should continue to make the strong case for the importance of immigration to the UK economy.

What it does mean is that the party should look to support small and medium sized businesses wherever it can in order to bring more choice and cheaper prices to the consumer. It should also champion much forgotten infrastructure projects, such as the ‘Northern Powerhouse’. Having recently been part of a coalition government that restored confidence in the UK economy, and with a leader whose expertise lies in business and economics, the party is well placed to do this.

The appetite amongst many Lib Dem members for the party to offer something more radical is understandable, but more radical does not have to mean more left wing; for example the legalisation of cannabis is a ‘radical’ policy that has support across the party. Other areas of radical policy that are likely to receive such support include introducing a negative income tax or shifting the focus of taxation away from income and on to unearned wealth, in particular the value of land.

There are motions being debated at this conference that seek to do this, but even then, they are wrapped up in the rhetoric of social democracy, not liberalism. By looking to become more left wing, the Liberal Democrats would only find themselves even more in Labour’s shadow.

Post-coalition and with Corbyn as Labour leader, the Liberal Democrats can no longer look to anti-Blair and anti-Iraq voters to propel themselves up the opinion polls. Diet Corbynism is unappealing when the full-fat version is freely available and in a strong position to take power. If the Liberal Democrats are to build a stable core vote and remain relevant they must forget the electoral tactics of the past and instead look to forge a new path where enterprise, opportunity and prosperity are at the heart of everything they do.