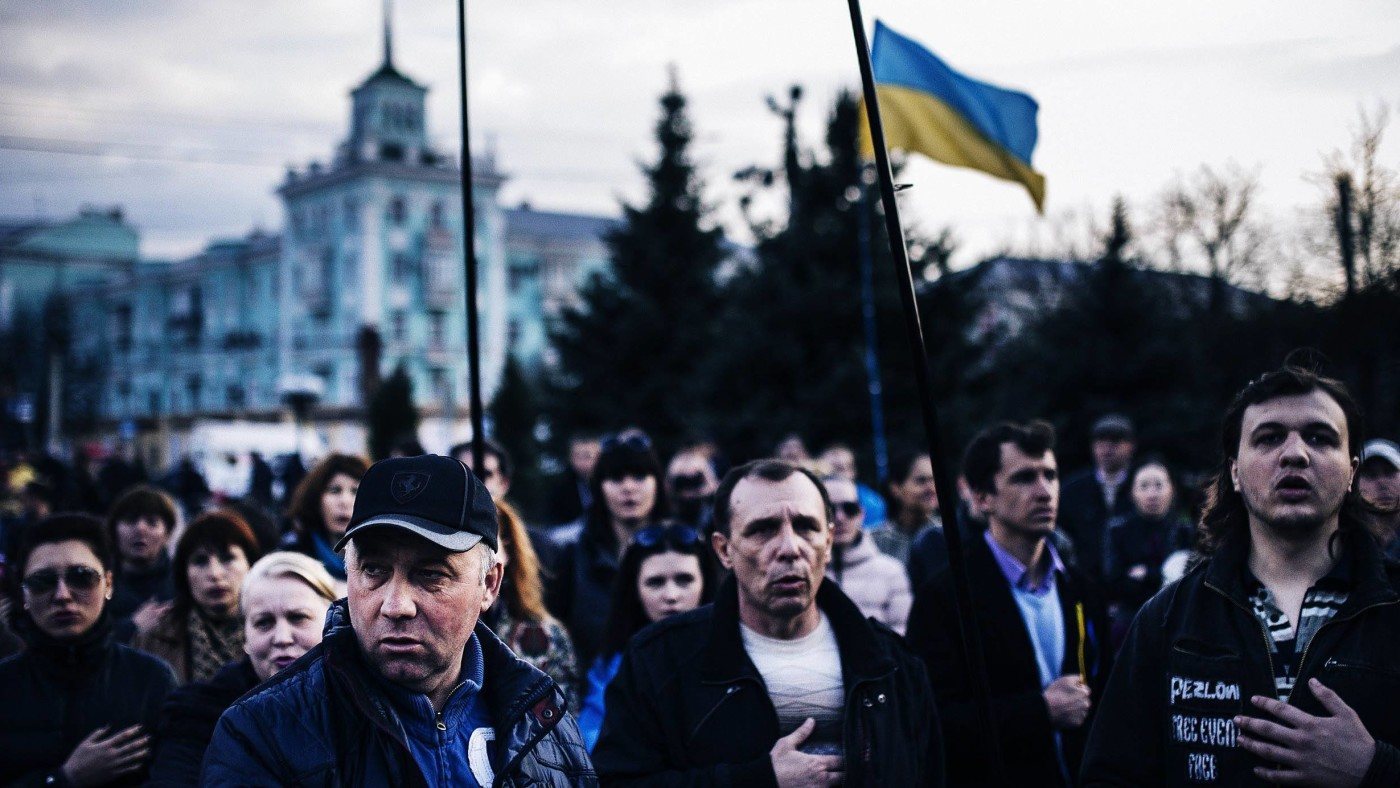

The revolution on the Maidan has not seen an end to corruption in Ukraine.

While attempts to bring corruption under control have been far more public and meaningful than in the Yanukovych era, the rot has not been stopped.

The strength of existing corruption and organised crime networks, continued and open warfare between President Petro Poroshenko and oligarchs such as banking and media mogul Ihor Kolomoyskyi, as well as the continuing distraction of the slow burning Donbass war, has limited the ability of the government to engage in effective reforms.

Olga Bielkova, member of Ukrainian Parliament for the Petro Poroshenko Party, noted how political wrangling impacted upon the reform agenda.

“Some of the new elites with little political experience, but a lot of ambition, get co-opted into complicated power struggles. Some get seduced by power, others don’t even know that they have become pawns in a bigger game they don’t even understand. Old elites, in the meantime, go for affected pronouncements and half-measures that don’t threaten their wealth or political influence. They often get cold feet when the idealist-reformers push ahead with transformative reforms; and so the spectacle is created to divert the public’s attention.”

Inna Sovsun, Ukrainian universities minister, gave one example of how higher education was affected by deeply entrenched corruption.

“Some of the top public universities are very entrepreneurial, and not in the good sense of the word. Some of the university rectors would open a private university with a very similar name to those of the more prestigious public ones. These would typically be registered to tiny private flats, with no pretence of a campus.”

Students would not actually do any work at these “universities”, merely being listed as studying on the public record.

“In their last year of studies they would then transfer to the public universities, and receive their legitimate diploma without really studying there. So many people simply bought these diplomas. The biggest problem isn’t even the cost of the corruption. It is the destruction of trust in the system of education.”

The education ministry has been very limited in its ability to shut these schemes down. “People who are used to earning so much money though these schemes are suing the ministry. Even one of our own MPs, who ran one of these programmes, is suing us. And in a legal system that is not operating as it should, it is really difficult to win”.

Likewise, in such contexts, basic infrastructural issues are holding back development.

Ukraine is one of the most energy inefficient countries in the world. Nowhere is this more abundant than in the housing sector. The Soviet era blocs were built cheaply and on the assumption of abundant energy supplies. As such, these properties were usually built around a central gas furnace with two settings, hot or cold, and burn gas at a rate of knots. As a consequence, Ukraine has been left further dependent on Russian oil and gas supplies at a time when this is politically most damaging.

Such issues have been worsened by the war in the Donbass. It has meant, in very basic terms, more money being spent on guns rather than butter fighting off Russian-backed forces. But it has also driven the legislative agenda. While attempts have been made to improve openness and efficiency – for example, recent digitalisation and computerisation measures introduced to the Ukrainian parliament this week to make corrupt practices more difficult – crude nationalism has been a major distraction. Instead of deepening links with strongly democratic countries, the government spends time legislating on de-Communisation, in practice simply forcing products such as “Soviet Champagne” to change their names name. In blunt terms, something that should not be a policy priority in such a time of crisis.

The West’s ability to assist Ukraine with these issue face significant constraints.

In power terms, Russia will not accept a Ukraine that moves overtly westwards. In a world where big states with lots of guns and a willingness to use them can still exercise meaningful power, as Russia has shown in Georgia, Crimea and Chechnya, it is willing to pay a high price in blood and bullets to hold onto its remaining influence in Ukraine.

This expansive nationalism, aiming to reclaim Russia’s imperial influence in Eurasia, is a powerful driver behind Putin’s power base at home. While many in the Russian middle class do not agree with his methods, that Russia should be an influential player in the region is a popular policy, and ensures Putin is tolerated by power brokers at home.

While Putin’s idea of a greater Russia is to some extent a prison, any withdrawal from this would damage his vertical of power. His ideological position means he would be unlikely to in the first place. Thus, while Putin can be negotiated with over some issues, Ukraine’s geopolitical status is not up for debate with him.

So the question is, in this sort of situation, how the West should react, especially when Ukraine has in many ways dropped off the headlines with the de-escalation of the Donbass war.

Unfortunately for the Ukraine, with all the will in the world, Russian intransigence makes full institutionalisation into Western alliances such as NATO and EU politically impossible in the short term. Russia, despite its distractions in Syria, has the network of influence and the willingness to deploy regular military units in eastern Ukraine to reignite the war and to wreck the region, should it wish.

For all the willingness among Western capitals for Kiev to move westwards, this is not willingness without cost. Western states will not risk war with Russia for Ukraine’s sake, and they should not.

However, Putin, while a powerful leader, will not last forever. In the long term, in the context of the oil crash, rising economic concerns over growth at home and the possibility of overstretch in the Middle East, Russia simply does not have the funds to credibly maintain such an aggressive position forever. And while Putin today does enjoy a dominant position today, even Stalin died of old age.

Just as Russia uses covert operations to destroy and coerce, so Western states can use the same tactics to influence the course of policy in Ukraine, and to lay the groundwork for the future. Simple measures such as deepening links with Ukrainian institutions and ministries, measures to improve trade, and investment, can be powerful drivers of internal reform. By keeping such programmes out of the public eye, as well as playing down their scope, Russia can be denied an excuse to intervene, increasing the costs it would face in the international community for unwarranted aggression.

NATO’s “building integrity” programme is just one example of this, arranging a staff exchange programme between Ukrainian and NATO state ministries. For Ukrainian officials working on these kinds of programmes, it is these sorts of institutional learning exercises that can instil the anti-corruption norms within the Ukrainian government that are really needed to fight graft.

Low levels of corruption in the West are not the result of any inherent superiority or goodness, but the strong institution of norms within government circles that corruption is both wrong and inefficient. The use of such soft institutionalisation can make a big impact on cutting it down in Ukraine as well.

While we should be wary of provoking Russia, but this does not mean that Ukraine must be abandoned to the Russian sphere of influence. Where there is a will, there is a way, and the Maidan showed Ukraine has just that.