For those of a conservative disposition, the never-ending conflicts that continue to keep the culture wars aflame usually make for depressing reading. Barely a week goes by without something either worrying or mad (or both) being reported in the press. The ‘great awokening’, which some would claim is now a decade old, continues to dominate public opinion as it challenges long-established conventions and institutions in the most fundamental ways possible.

Of course, the culture wars are amorphous, with no agreement on how coordinated they are (or even whether they exist at all). For some commentators, usually from the right, the future of Western civilisation is at stake, for others (usually from the left) ‘wokeism’ is an alarmist term, when in reality the debates around gender, race and faith are fights for equality.

Having said that, when a liberal left singer-songwriter like Nick Cave admits he is appalled by ‘woke culture’ because of its ‘lack of humility and the paternalistic and doctrinal sureness of its claims’ one can’t help concluding that the Overton window has shifted again, and the intimidation and fear that has stopped too many people from a very wide political spectrum feeling they can debate divisive issues is lessening. That is a sign of some progress at least.

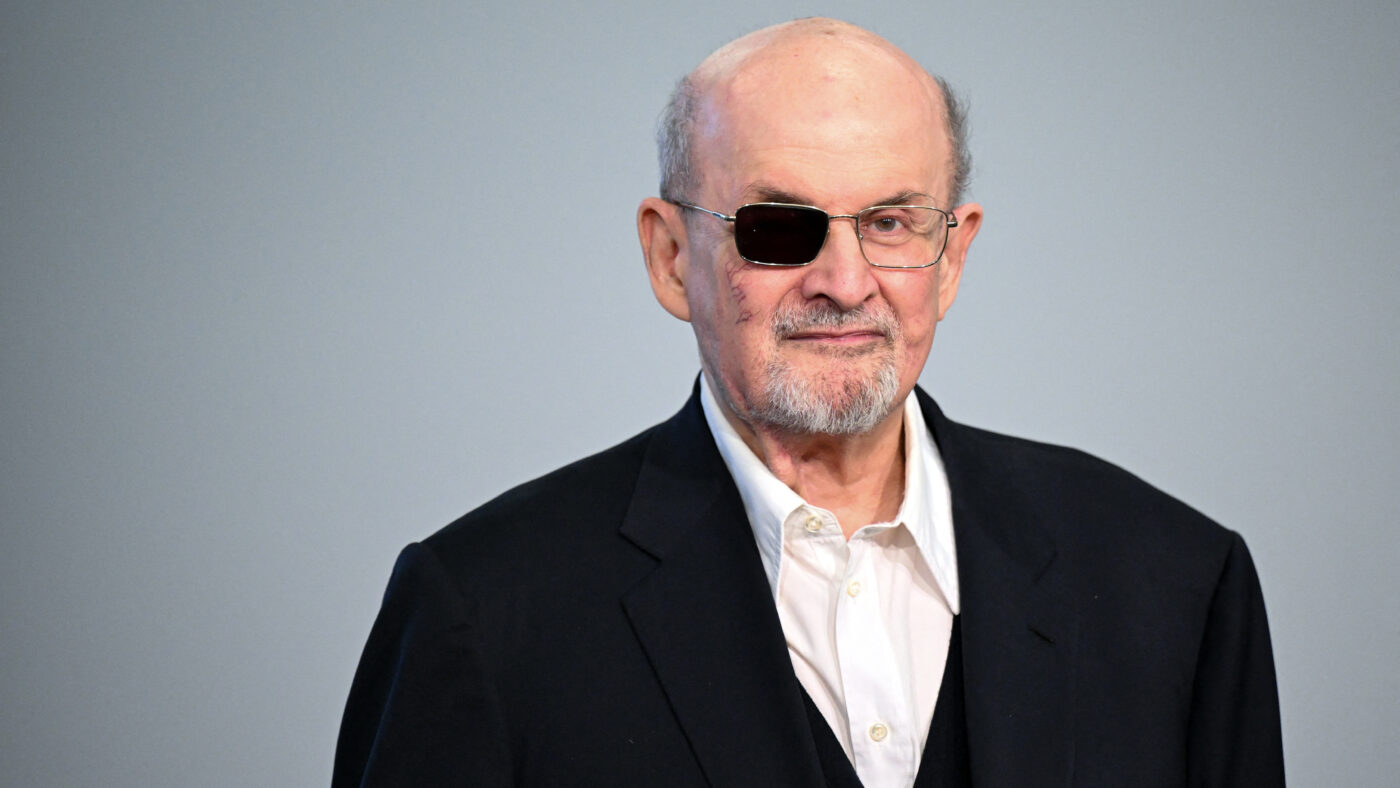

Over the last week there has been more good news, with several unrelated but encouraging developments that show that any Spenglerian End of the West is, for the moment at least, delayed. First, the Cass Review introduced a necessary dose of evidence-based objectivity into the often toxic and unscientific arguments on gender; then the High Court ruled that Michaela School, and its Headteacher Katharine Birbalsingh, were not guilty of discriminating against a Muslim student who had been stopped from observing her prayer rituals. Lastly, we have seen the re-emergence in the public sphere of Sir Salman Rushdie, who recently published his account of his attempted murder in a memoir entitled, bluntly, ‘Knife’.

Rushdie was recently interviewed by Erica Wagner at the Southbank Centre via a video link from his home in New York (he is understably wary of speaking live on stage). Even if he was only there virtually, it was, nonetheless, genuinely moving to see him there at all, less than two years after that nearly fatal attack in upstate New York. That attempt on his life, from a lone assassin, lasted 27 seconds, ‘a long time’, he said, ‘when the other person is holding a knife’. But he was, apart from the loss of sight in his right eye, ‘repaired’, and his views about freedom of speech were seemingly only strengthened by his harrowing experiences.

Rushdie is, of course, the first and most famous victim of the modern trend of being censored for writing something that others find offensive. But his ‘cancellation’ was very real and visceral: the fatwa issued on Valentine’s Day in 1989 by Ayatollah Khomeni, had lasting political (and personal) implications, which came back to attack him, to drag him back into his past, when he stood up to speak in Chautauqua Institution about the importance of keeping writers safe from harm. Irony stalks him as well.

All those who remember the death sentence being passed in Tehran will recall how dark a moment it was. We watched copies of ‘The Satanic Verses’ being burned on the streets of England and suddenly we felt a sense of dislocation from our country, from those we lived alongside. Rushdie confessed that even then his irrepressible optimism continued: ‘I knew’ he told the audience ‘that it wouldn’t end then’. One of the most depressing consequences of the fatwa was the pusillanimous response some other writers greeted it with: Roald Dahl, Germaine Greer, John Berger, John Le Carré, amongst others, publicly criticised Rushdie for having the temerity to express himself freely as a writer. Rightly, the hurt he felt then from their words endures, because as Rushdie said to Wagner, ‘words are the victors: they outlive empires’, and they outlast the lives of their authors, for good or bad.

If the late 1980s were a dark time for freedom of speech then we live, if anything, in an even darker period of intellectual, moral and physical cowardice. But Rushdie’s refusal to be silenced continues to shine a light on those who, because of some contorted form of relativism, refuse to support him in public for fear of causing offence. We know the enemies of freedom of speech are not only those who burn books; they are also those who refuse to stand by the authors being attacked. Le Carré is gone, but in his place we have not just modern day apologists for the fatwa in figures like Bernardine Evaristo, and institutions that she, as President of the Royal Society of Literature, represents. They are determined to remain ‘neutral’, when such a position is in itself a partisan, political, and cowardly act. At the end of ‘Knife’ Rushdie quotes John Locke, who wrote: ‘I have always thought the actions of men are the best interpreters of their thoughts’. To that you can add inactions as well.

And that, perhaps, is the crucial difference between the 80s and now: it is institutions, as well as influential individuals, that show a similar lack of moral strength. Birbalsingh, Cass, and Rushdie, have predictably been met not with universal relief by those who benefit from living in a country that allows freedom of expression, but with threats of violence, of calls for censure. Wagner asked Rushdie why, for such a rationalist, his books continue to contain moments of magic, and of miracles. ‘Because’, he said, ‘the world has abandoned reality. We live in a world of surrealism’. Rushdie’s survival was one of luck and the miracle of science, of empirical knowledge, and of hope and love. His presence continues to remind us that we need these qualities now more than ever, but too often they are at risk from both the forces of darkness that have followed him since that unlovely St Valentine’s day in 1989, but now they are also joined by those who look upon such terrible acts and say nothing in case they offend those who prefer to use knives, not words, to censor and silence.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.