Thursday’s election results looked pretty awful for the Conservatives. But once you dig into the details, they seem utterly terrifying.

Their main problem is that they are losing the generation game. During the election campaign, Oliver Wiseman visited Britain’s oldest and youngest constituencies, to illustrate the way that British politics is now driven by age rather than class.

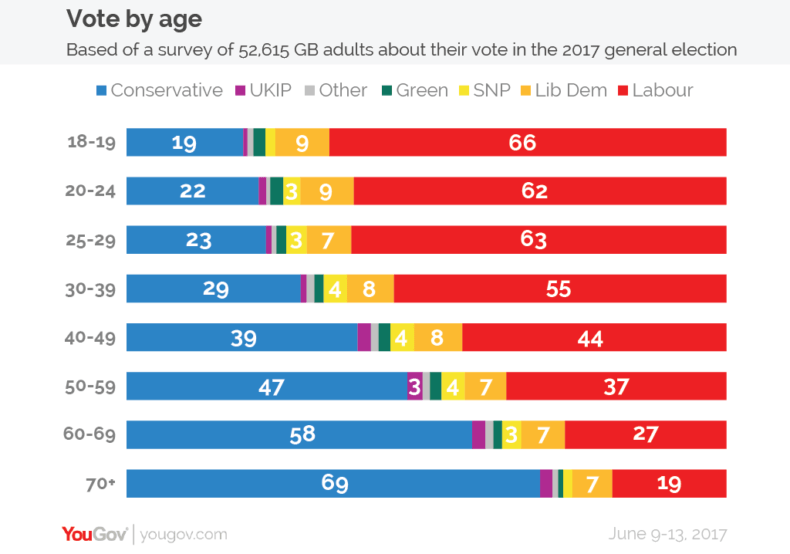

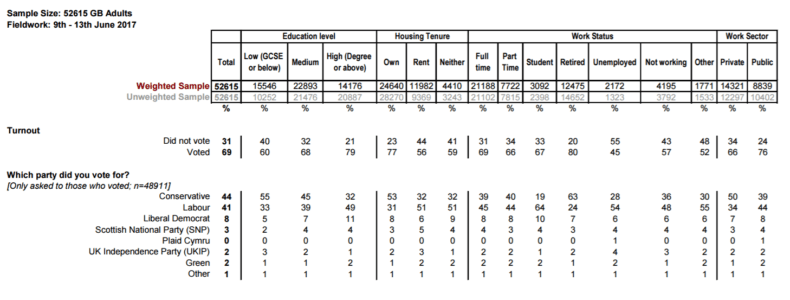

But this isn’t just about hordes of youthful Corbynistas. As a new mega-poll from YouGov of more than 50,000 voters shows, Labour is winning over the middle-aged, too. It’s not until voters reach their fifties that they become solidly Tory.

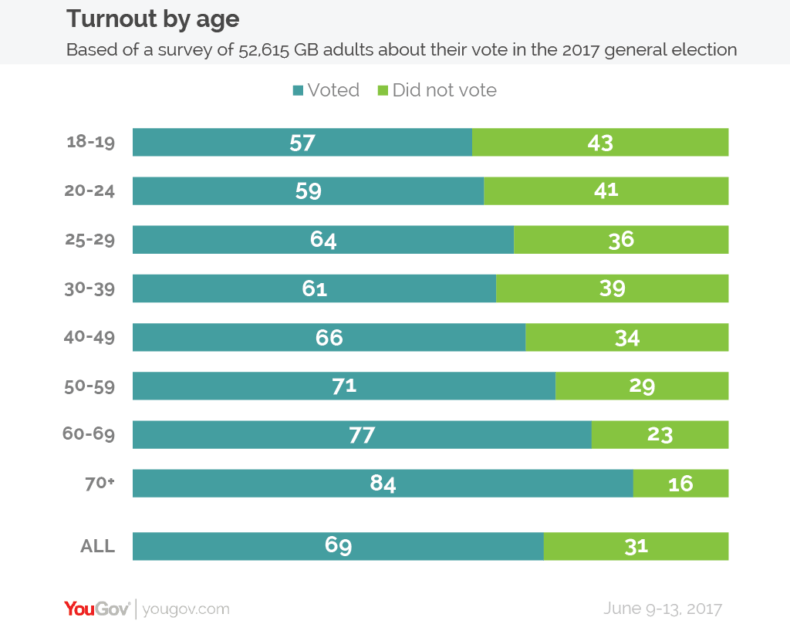

Yes, these older voters still turn out in large enough numbers to give the Tories a natural demographic advantage. But even they can’t deliver a majority on their own.

But what’s really worrying the Conservatives – or at least the smarter ones – is what happens next.

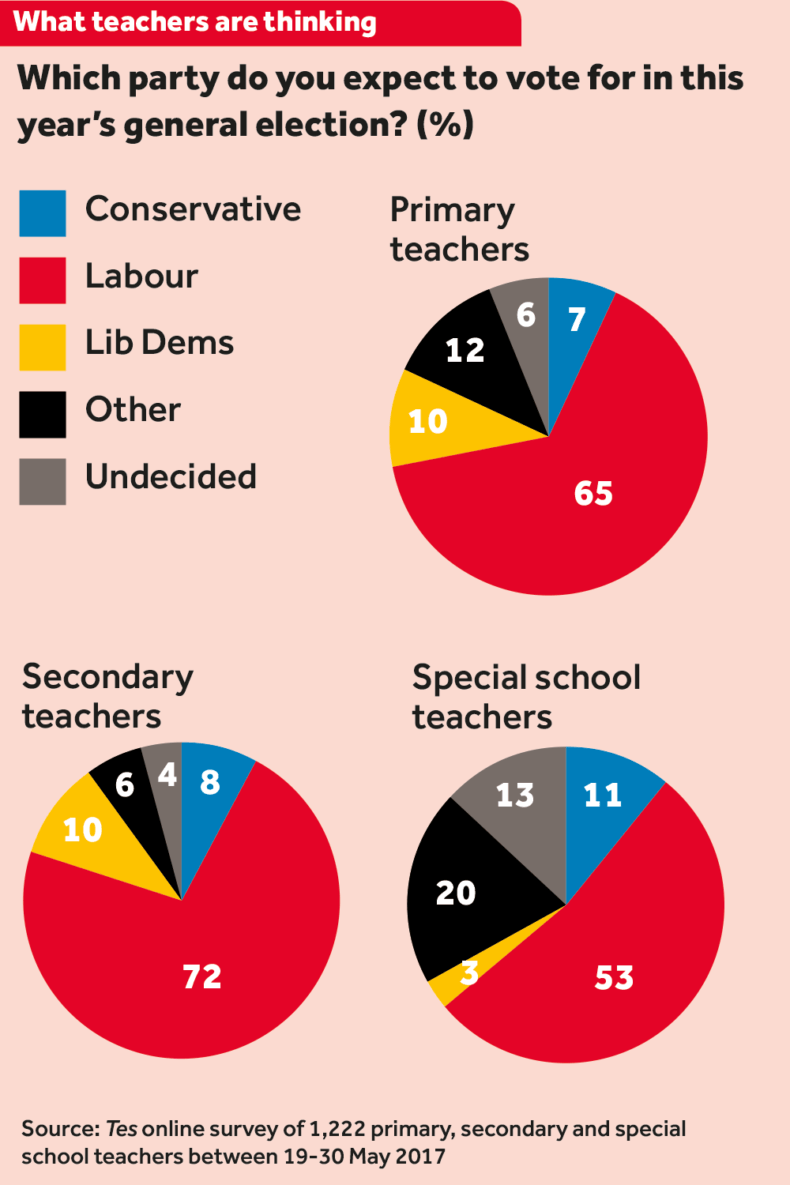

There was a bit of a fuss on election day when a primary school in Hackney being used as a polling station displayed pro-Communist slogans, drawn by the children, in its windows.

It was illegal – but not atypical. A Times Education Supplement round-up of mock elections at schools found that 72 backed Labour, and just 15 backed the Conservatives. More to the point, the teaching profession is now solidly behind Labour. Back in 2010, just 25 per cent of teachers voted Labour – down from 43 per cent in 2001. By 2015, in the wake of the Gove reforms, that had risen to 44 per cent. And shortly before the election, a TES survey put it at an incredible 68 per cent – with just 8 per cent voting Conservative.

This is, admittedly, an online survey, so self-selecting. But those surveyed only went for Labour by 51 per cent in 2015 – only slightly higher than the industry as a whole.

There are many possible causes of this – a general shift to Labour, May’s plan to reintroduce grammar schools, but above all the school funding cuts.

I was one of those who pointed out that, since funding per pupil has doubled in real terms since 1997, the proposed cuts were more of a haircut than an amputation. But clearly it is less than optimal in political terms – thunderingly catastrophic would be a better way of putting it – to call an election when a massive grassroots campaign against the cuts is already underway.

In the days and weeks before polling day, voters were receiving letters from teachers and head teachers spelling out precisely how many staff would have to be fired if the Government were to get back in and impose its Savage Tory Cuts. Senior Conservatives I have spoken to are convinced that without the cuts, and those letters, their party would now have a majority.

The result of all this is that, for many on the Right, looking into the future looks like staring down the barrel of a gun. They see a generation of eager young Corbynites emerging from these educational madrassas, trained by their teachers to regard Conservatives as lower than vermin and the market as an engine of inequality.

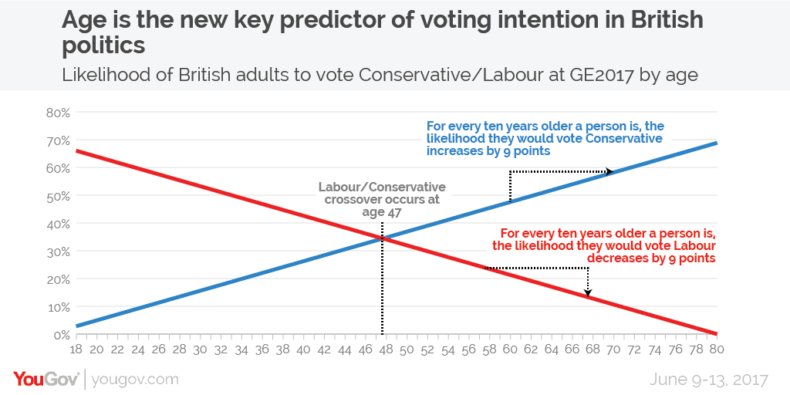

There is, of course, a case that this has always been true to some extent: think of that old adage about young people who vote Tory having no heart, and grown-ups who vote Labour having no brain. YouGov’s own figures show that voters grow more Tory as they get older, shifting nine points to the Right with every passing decade.

Yet this, crucially, is a snapshot rather than a prophecy. Just because the crossover point is 47 now, it does not mean it could not be 37 at some point – or 57.

And this is where the housing issue comes in. The truth is that people do not just become Tories as they age. As Margaret Thatcher knew when she brought in the right to buy, they also become Tories when they own their own homes.

Between 1966 and 1997, the Tories maintained (aside from a few blips) a lead of roughly 30 points in the polls among owner-occupiers. That fell when Tony Blair won back the middle classes, but has since rebounded. According to the new YouGov poll, 53 per cent of homeowners voted Tory last week, and 32 per cent voted Labour. Among renters, it was precisely the reverse: 51 per cent for Labour, 31 per cent for the Tories.

The YouGov survey does not break down the figure by age – obviously, older people are more likely to have houses. But as James Kanagasooriam of Populus explains, home ownership is part of a complex of life markers that tend to be associated with Tory voting: being married, having a fairly high earning job, owning multiple cars.

The bedrock of the Tory vote, he says, is rural and suburban affluence and the behaviours, markers and lifestyles associated with it. This, along with the grey vote, is the Tories’ electoral firewall. Most Britons own homes, and homeowners are much more likely than renters (77 per cent vs 56 per cent, on YouGov’s figures) to turn out to the polls.

The problem is that this firewall is shrinking.

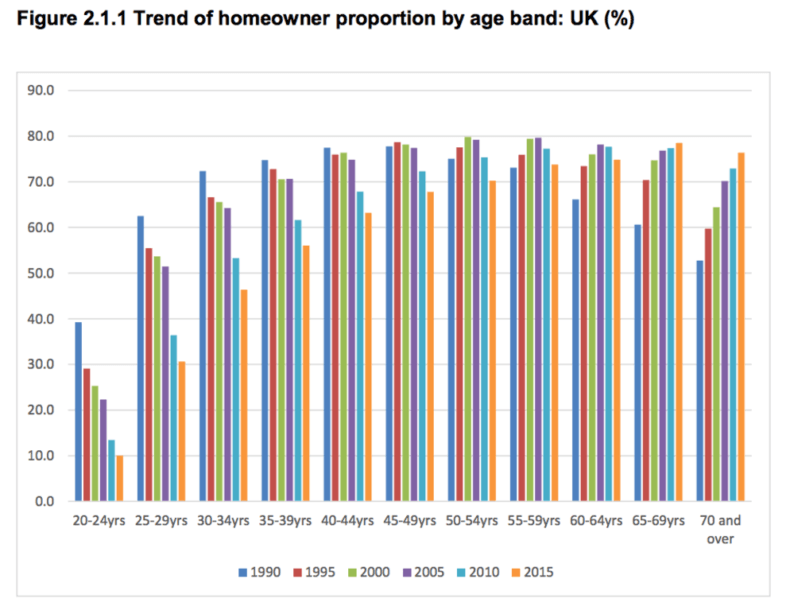

In 2015-16, 62.9 per cent of Britons were homeowners – the lowest proportion in 30 years, and down from 70.9 per cent as recently as 2003. Since 1990, ownership among the old has grown. But ownership among the young, as this chart from the Social Mobility Commission shows, has fallen off a cliff.

Back in 2010. my friends Ed Howker and Shiv Malik published a book called Jilted Generation. Its argument – which now looks downright prophetic – was that the generational playing field had become hugely tilted towards the old and away from the young.

One of the points they made was that the housing crisis is doing social as well as economic damage. People in Britain tend to wait until they have homes to start families. If they can’t get homes, they don’t have kids, or at least not as many – especially not if they’re still living with their parents. They cited polling showing that up to 2.8 million people aged between 18 and 44 were delaying marriage because of their housing situation. Some 385,000 couples – three times the number getting married in the average year – had put off their vows.

The economic and social costs of this – the workers stuck in the wrong place, the families that have shrunk or never formed – represent arguably the greatest public policy challenge this country. But it also represents an existential threat to the Conservative Party, or at least to its long-term prospects of keeping power.

While I was working at the Telegraph, I spent many hours in leader conferences arguing against its position on planning. This was summed up by a staggeringly successful 2011 campaign called “Hands Off Our Land”, which marshalled the support of some of the country’s best-known and most passionately supported organisations – the National Trust, the Campaign to Protect Rural England, the WI, the RSPB, Friends of the Earth, English Heritage, Greenpeace, the Football Association, the WWF, you name it – to force the Coalition to water down its proposed planning reforms.

The campaign was couched in terms of saving Britain’s precious countryside. But it wasn’t hard to detect the streak of NIMBYism running through it. Yes, of course we need more houses, the argument went. Just not where any of our readers can see them.

At the time, the political logic for the Conservatives still dictated that they should bow to their core vote. But if they do that for long enough, there won’t be any core vote left.

The collapse of the social democratic vote across Europe was preceded, as James Kanagasooriam points out, by a collapse in the number of people with the appropriate lifestyle markers: union membership, jobs involving manual labour. As the proportion of people living Tory lifestyles shrinks, the Tory vote could follow suit.

Building more homes, in other words, is not just overwhelmingly in the national interest, but overwhelmingly in the Conservatives’ interest. Better get started.