We all know why Brexit happened. It was a rebellion by those to whom recent economic history hadn’t been kind. Who felt that the status quo hadn’t offered them what they had been promised – and who could ignore warnings of economic disaster because they had nothing to lose.

But does that story really hold up? Consider the two constituencies I visited recently.

In Constituency A, unemployment is practically non-existent, child poverty is almost half the national average and wages are markedly higher than the national average. In Constituency B, wages are below par, nearly one in three people grow up in relative poverty and 3.3 per cent of the workforce claim unemployment benefits, compared to a national rate of 2.6 per cent.

On those figures, you’d assume that a majority in Constituency A heeded the warnings of economic doom and voted Remain, while Constituency B overwhelmingly opted for change.

Except that isn’t what happened. Constituency A voted for Leave by 60 to 40. The Remain vote in Constituency B, on the other hand, was 70 per cent.

Constituency A is Christchurch, an affluent town on the south coast. Constituency B is Sheffield Central. And the demographic detail that explains the difference is simple: age.

I visited the pair, some 200 miles apart, as part of CapX’s tour of the country’s most interesting constituencies. In Sheffield Central, the median age is 26, making it the youngest constituency in Britain. In Christchurch, by contrast, the median age is 69, and 30.4 per cent of the population are pensioners – the highest figure in the country.

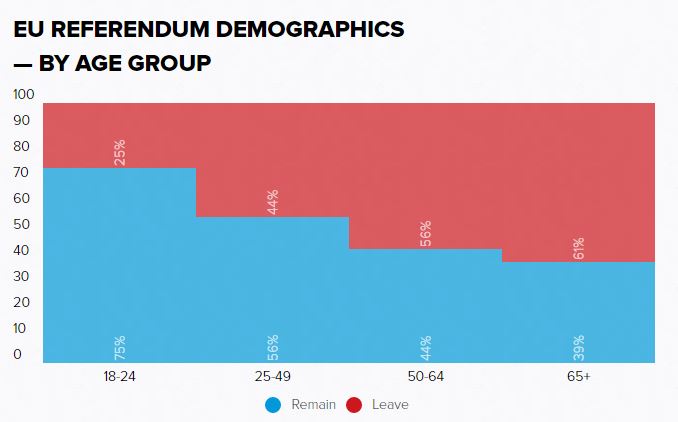

It is this age difference that made their radically different referendum results entirely predictable:

Source: Politico

But it is also this difference which illustrates one of the biggest transformations in British politics in recent decades.

For years, the best determinant of someone’s voting intention was class. But slowly, incrementally, something fundamental has changed. As YouGov’s Chris Curtis has pointed out, these days class tells you about as much about someone’s voting intention as reading their palms.

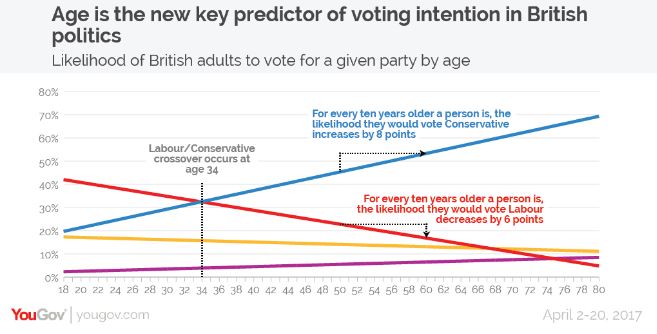

The big political giveaway now is age. For every extra 10 years, YouGov found, a voters’ likelihood of voting Conservative rises by 8 per cent, while the chance of them voting Labour falls by 6 per cent.

Source: YouGov

That is borne out in the politics of both Christchurch and Sheffield Central. Few places are as solidly Tory as Christchurch, where Christopher Chope – who at the age of 70 represents his seat in more ways than one – stacked up 28,000 votes at the last election.

Sheffield Central, by contrast, tells the recent history of the UK’s youth vote. Traditionally Labour territory, the student-dominated seat was almost captured by the Lib Dems in 2010: they came within 200 votes before their broken promise on tuition fees gave Labour’s Paul Bloomfield a comfy 15,000-vote majority five years later.

Of course, the generational divide is not just a political issue but a string of policy considerations too. Can the NHS and care system take the strain of our ageing population? Is retirement as we know it sustainable? Can we escape the housing Catch-22 which pits older Britons whose savings are tied up in their homes against younger generations who have, in many cases, been priced out of ownership?

Fittingly, I went to Christchurch on the Sunday after the publication of the Conservative manifesto. Given that the day’s front pages told of a “Dementia Tax Backlash”, with the Tory grassroots appalled at the manifesto proposal to reform social care, I expected Christchurch Conservative Club to be a hotbed of outrage.

Outside the red-brick building, which looked appropriately strong and stable, “Chris Chope Conservative” posters were draped across the first-floor balcony railings. As I approached, a mobility scooter whisked a pensioner past the doors. Another grey-haired passer-by typified the response reported in the national press. “People shouldn’t be paying more for something so important,” she told me, looking genuinely distressed. “It’s unfair. I thought things were supposed to be getting better, but everything is a right mess.”

Inside, however, the huddled groups of outraged silver-haired schemers that I had come looking for were nowhere to be found. Instead, some of the club’s sprightlier members played pool while others quietly nursed a postprandial drink.

Would Theresa May’s pensioner triple whammy – social care reforms, the means-testing of the winter fuel allowance and the scrapping of the pension triple lock – put you off voting Conservative, I asked one club member? He leaned back, crossed his arms and breezily told me: “There’s more to life than just accumulating wealth. I’m one of those people who has always been happy with the idea of arriving on this planet with nothing and leaving with nothing.”

His friend agreed, pointing out that “the Europeans do it differently, they aren’t as obsessed with owning homes and sitting on a pot of money. Lots of them rent. Lots of them downsize.”

Further to the front of the minds of those nursing drinks in the club was the prospect of John McDonnell, who had appeared on The Andrew Marr Show that morning, running the country’s finances. And of Jeremy Corbyn taking up residence in No 10.

The Conservative Club members might have been on-message, but they didn’t – at least anecdotally – appear to be the exception. One elderly voter told me he had switched to UKIP at the last election but would be returning to the Conservative Party this time. He wasn’t interested in social care reforms: “That doesn’t matter. I’m much more worried about Jeremy Corbyn and immigration,” he said.

Christchurch’s high street, with its teashops and funeral homes, hints at the town’s older-than-average population. In Sheffield Central’s, the impossibly cheap drink offers shout out loud that this constituency is dominated by students. Both Sheffield Hallam and the University of Sheffield fall within its boundaries, as does much of their student housing.

Shaffaq Mohammed, the Liberal Democrat candidate, sticks to the party line impeccably when he tells me that “the only issue coming up on the door is Brexit”. Is his party still paying the price among younger voters for its tuition fee reversal during the Coalition? “Brexit is a bigger issue,” he insists. “If the economy is in recession, then it doesn’t matter what fees you’re paying.”

Well, £9,000 is a lot of money, even when the economy is growing. But leaving that to one side, Mohammed’s view does seem to be echoed among the students I speak to. Their concerns are different to their older counterparts in Christchurch – and Brexit worries are high on the list – but tuition fees scarcely feature. Certainly, reinstating a free university education, as the Labour manifesto promises, doesn’t seem to be taken that seriously. “I suppose that would be nice,” says one engineering undergraduate.

Higher on their list of worries are some thornier, fiddlier issues to do with higher education. One postgraduate student is concerned about funding for academic research after we leave the EU. Another won’t be voting Conservative because of Theresa May’s less-than-open-armed attitude to foreign students. Interestingly, housing – the trickiest policy area when it comes to the generational divide – isn’t mentioned.

In places like Sheffield Central, these specific concerns are part of a broader worry that Theresa May wants to refashion the country according to a more suburban, less metropolitan vision.

And that is the point about Britain’s new generational dividing line. Too many fall into the trap of seeing it as battle of interest groups. Young versus old, squabbling over taxpayers’ money.

Of course, there are policy trade-offs – but generational politics is, first and foremost, about disposition and outlook.

This is a point that has been missed by politicians of all stripes in recent years. David Cameron and George Osborne were happy to divide and conquer when it came to the generational gap, with the young – who are less likely to vote, and even less likely to vote Conservative – bearing the brunt of spending cuts.

Nick Clegg, meanwhile, has happily exploited the generational divide in the other direction, painting Brexit as a selfish attack by the old on the young. Speaking in the House of Commons during the Article 50 debate, he claimed the Government had “very deliberately decided to ignore the pleas, the dreams, the aspirations and the plans of the people who should actually count most. It is our children and our grandchildren, the youth of Britain, who will have to live with the fateful consequences more than anybody in this House or anybody on the Government front bench.”

So widespread was the portrayal of the Brexit vote as a selfish act by older voters – an argument which depends on the flimsy logic that because older voters will die sooner, they somehow cease to make rational political decisions – that someone even had to point out that taking the vote away from pensioners would be a bad idea.

As Robert Colvile pointed out on CapX, the Conservative manifesto actually made for a welcome change from these divisive approaches. It not only listed the ageing population as one of the “five giant challenges” facing the country, but devoted an entire section to “restoring the contract between the generations”. And it laid out the case for action in a conciliatory, One Nation fashion:

No grandparent wants to see their grandchildren worse off than they were, yet that is precisely the fear many older people now have. No son or daughter wants to see their parents poorly cared for or their hard-earned assets whittled away, yet that is the reality for too many old people in care. We must admit that the solidarity that binds generations is under strain in our country.

And it was precisely this seriousness about a fresh approach to Britain’s generational politics that made May’s social care U-turn on Monday so perplexing. Had her team not foreseen that a drastic change in direction would need robust advocacy?

Initial polling on the policy was actually far from disastrous, with 40 per cent opposed and 35 per cent in favour. And that was before she had made the case for the reform beyond the manifesto launch.

Had she done so, my experience in Sheffield and Christchurch suggests, she would have found a receptive audience. Christchurch’s pensioners, for example, are parents and grandparents. The voters I spoke to seemed alive to the generational challenges the country faces and open-minded about the policies needed to tackle them. They seemed ready to restore the contract between the generations. But will the Prime Minister still have the courage to take action?