Shortly after becoming prime minister six years ago, David Cameron reiterated his much-mocked idea of a national “happiness index”.

“It’s high time we admitted that, taken on its own, Gross Domestic Product is an incomplete way of measuring a country’s progress,” he said, before going on to quote Robert Kennedy’s endlessly repeated dictum that GDP captured everything “except that which makes life worthwhile”.

He was right to promote this idea – although like some other smart suggestions from his optimistic days as shiny new opposition leader, the concept was downgraded in government.

GDP is a pre-war measure from an age dominated by heavy industry, designed to calculate a nation’s economic production. It has evolved to become the key device used to weigh a country’s economic success, tweak taxes and tackle inflation.

Yet the measure works less well with the growing importance of services. And as Kennedy correctly pointed out, it also ignores the most important aspects of people’s lives.

The Legatum Institute, a think tank, has responded to such concerns with its own Prosperity Index, now in its tenth year and covering 149 countries. It seeks to shine a spotlight on “the journey from poverty to prosperity” – a subject that causes such fascination for economists.

Legatum ranks nations on nine areas such as economic quality, personal freedom, health and safety. In an important change, the environment has been added. The results, although subjective, offer an interesting global snapshot of wealth and wellbeing.

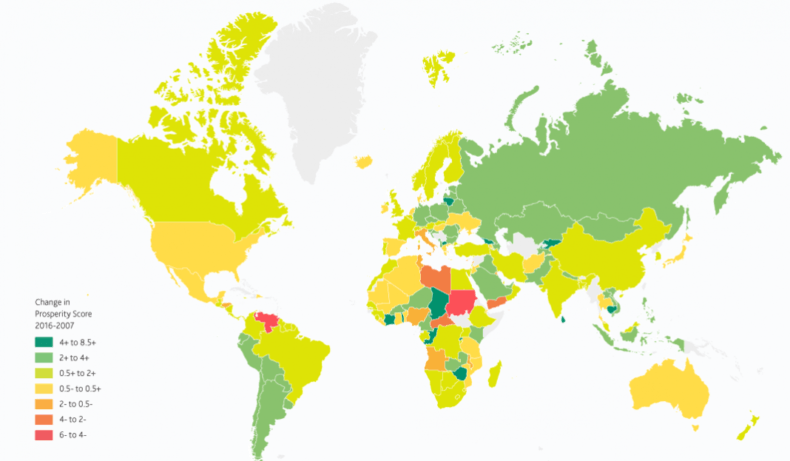

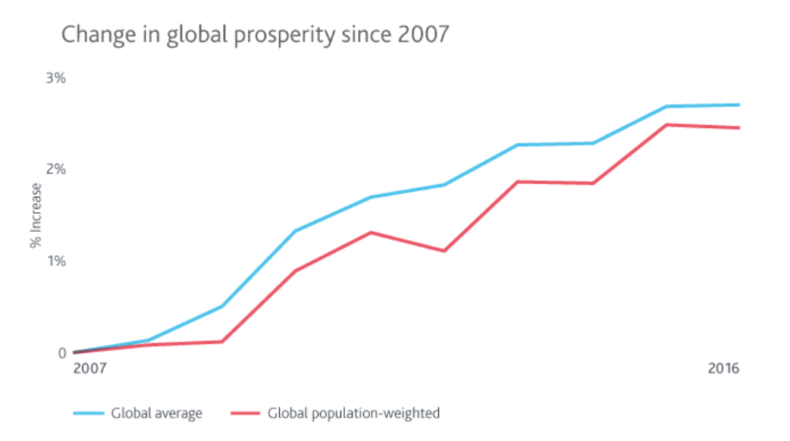

Most importantly, the study underlines that for all the malign pessimism and crude populism that dominate headlines, the world is – on these broad terms – becoming more prosperous. So Finland’s GDP per capita may have decreased sharply, but Legatum argues that its real wealth, in terms of its citizens living in a free, safe and successful nation, has improved.

One key motor of progress highlighted by the report is the openness of European societies and their growing multiculturalism. Yet at the same time, this is also driving the resurgence of racist rabble-rousers on the Right and outmoded anti-capitalists on the Left – an angry backlash that threatens Western prosperity.

Legatum also makes another welcome claim, that “global prosperity inequality” is falling as nations at the bottom improve faster than those at the top. This can even be seen in Europe, with eastern nations rising on their measures faster than the west – although hampered in places such as Hungary and Poland where reactionary rulers are restricting hard-won freedoms.

The report effectively endorses the “catch-up” theory which argues that advances in health and technology can overcome problems caused by lack of capital; some predict all economies will converge eventually.

Certainly plenty of countries, from China to Chile, have shown convergence towards the United States, the world’s biggest economy, over the course of my lifetime.

But as a recent study by Renaissance Capital (not available online) showed there are also plenty that have lost ground since my birth in 1962 including important African states such as Nigeria, South Africa and Zimbabwe. The socialist nirvana of Venezuela is another key loser, suffering the sharpest prosperity decline over the past decade of these reports, amid rising social tensions.

Similarly, oil is again exposed as a curse for developing countries, corroding democracy while fuelling corruption and rent-seeking activities.

The critical factors fuelling prosperity, as the think tank rightly points out, are open markets, high personal freedom and strong civil society. This is not rocket science.

But given the fragility of such ideas, fury against globalisation and rising mood of ugly intolerance, it is always good to restate these important points.

And what of the UK? We come third for generating prosperity, despite sluggish growth, thanks to structural reforms introduced by the government – but tumble down the ratings to tenth overall due to a failure to share wealth. This is something seen across the West, helping open divisions in societies to alarming degree.

For Britons, of course, these results will be seen through the prism of Brexit, which will redefine our global relationships – if Theresa May can negotiate the economic, political and social minefields of extrication from the European Union.

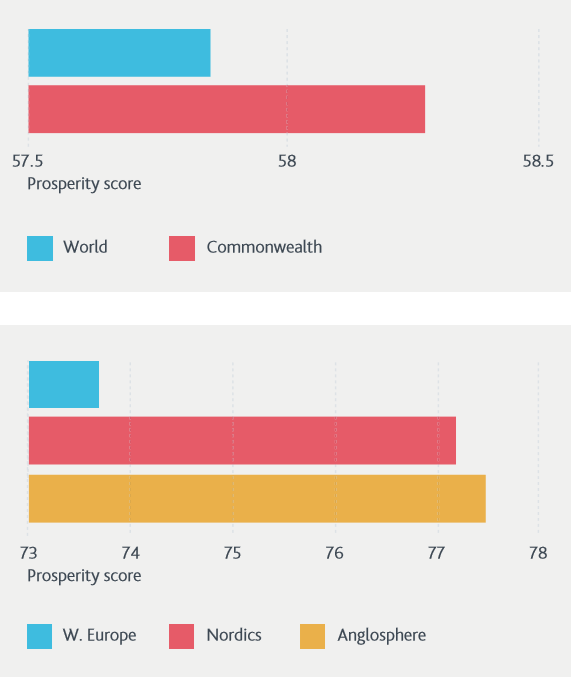

Thus the authors make great play of what they call “the Commonwealth Effect”, arguing that developed “Anglosphere” of Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom delivers greater prosperity than any comparable block.

Yet this hardly surprising, given the exclusivity of such a small club. We must bear in mind, in plotting our future relationships, that the collective economic weight of the other three highlighted nations is a fraction of the size of the 27 being forsaken in Europe.

But it is interesting to see New Zealand picked as the planet’s most prosperous place, edging out Norway and Finland. This isolated nation is reliant on agriculture for its economy and its exports – a sector that thrived after a Left-leaning government started to ditch subsidies in 1984.

Farmers screamed this would be a disaster, driving them in droves from the land. Instead they were forced to cut costs, innovate and respond to demands from consumers rather than bureaucrats. Now, they are some of the world’s most efficient and inventive producers.

If only British politicians might be so bold when we are free of the distorting Common Agricultural Policy. Sadly, I fear they are far more likely to chuck state cash at the powerful farm lobby.

Baroness Stroud, the think tank’s chief executive, says her prosperity index is “the clearest lens” through which to view the world.

This is an inflated claim – not only is there a clear correlation between traditional measures of GDP and fresher efforts to gauge prosperity, but the study has its flaws. The authors have, for instance, fallen for the myth of Rwandan success, overlooking the extreme repression and lack of political freedom under a bloodstained despot.

Yet Baroness Stroud is surely right to argue progress and prosperity is as much about social wellbeing and human contentment as about economic success – and Legatum deserves credit for promoting such ideas.