There are two popular theories about the labour market. The first is that automation is clawing its way up the wage scale, throwing the shelf-stackers out of work before setting its sights on the lawyers and the doctors.

The next is that the job market is being hollowed out from the middle. The inevitable culmination of capitalism, argue its critics, is an economy riven by inequality, polarised between high-wage, high-status CEOs and low-wage, low-status peons, with the middle class vanishing into the ether.

Even relatively restrained analyses tend to stir up these fears. This week, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics released its 10-year forecast for the job market. The only growth industries, as The Atlantic puts it, are “nurses and nerds” – with inequality surging in the process. And that’s before automation really starts to clench its unforgiving robot jaws.

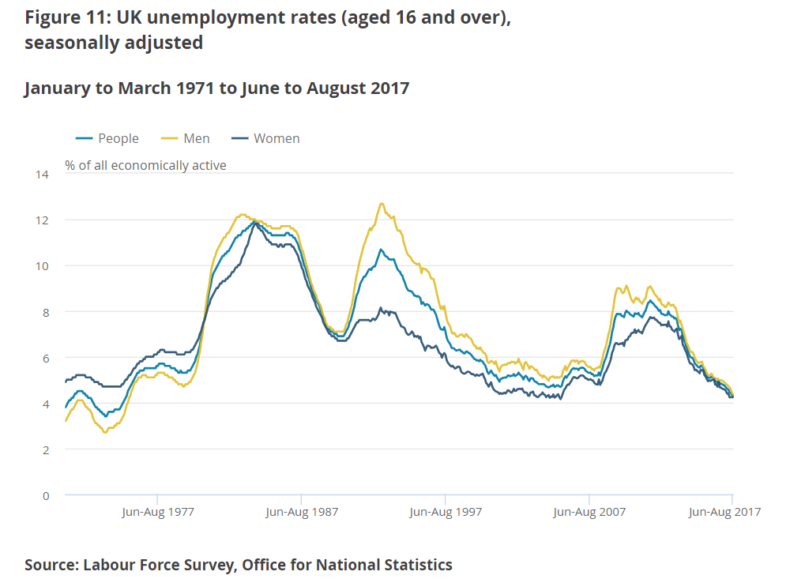

But there’s something weird going on here. We are in the midst of a great mass panic about technology tipping us all into unemployment – hence the adoring reception given (mistakenly, in my view) to the universal basic income. Yet this comes at a time when the economy – certainly in Britain – is creating more jobs than ever. The unemployment rate hasn’t been this low since the Wilson government.

And it’s not just Britain. As Tim Worstall pointed out a while back on CapX, the chance of any given American losing their job in any given week is 0.15 per cent. Back in the Fifties, Sixties, and Seventies, that figure was almost twice as high. So it’s entirely arguable that our problem today might not be too much churn in the job market, but too little.

Likewise with automation: as Neil O’Brien MP says, British factories use fewer robots than Slovakia’s. If we want to increase productivity, and prosperity, don’t we need to welcome our industrial robotic overlords rather than (as Labour suggests) taxing their use?

Re Corbyn's "robot tax" – UK has very low robot use – lower than Slovakia. To increase wages we need more not less. Tax break not increase! pic.twitter.com/1Xeb2mJqGC

— Neil O'Brien (@NeilDotObrien) September 27, 2017

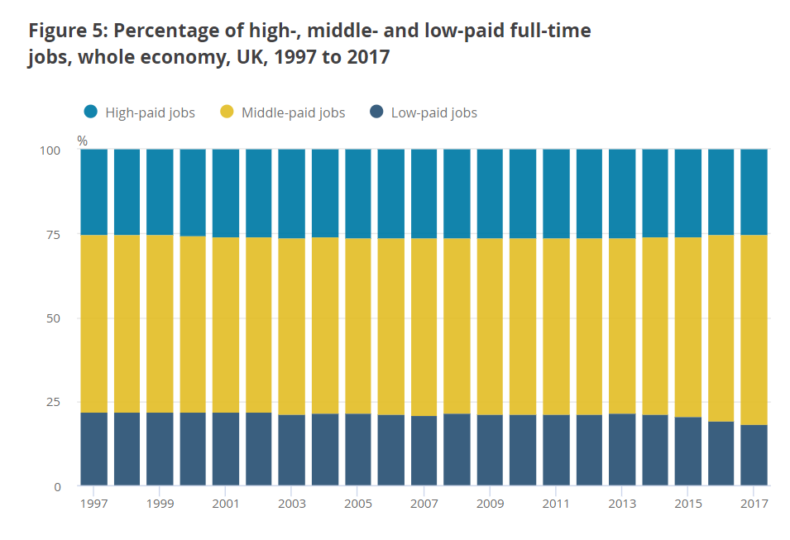

There’s a similar contradiction when it comes to the second theory – about the polarisation of the labour market between rich and poor. For the distinguishing feature of the ONS’s latest Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, released this week, is that the number of jobs in the middle has been growing, rather than shrinking.

Partly, the statisticians explain this as a consequence of the introduction of the introduction of the National Living Wage. But it’s not that clear-cut.

The ONS uses the OECD’s definition of low pay, which is two thirds of the median hourly wage. That wage is now £14, meaning that the low-paid get £9.33 an hour or less.

The National Living Wage, by contrast, is currently £7.50 (for those over 25). Which suggests either that its introduction has triggered pay rises further up the scale, or that many of the jobs being created are not so menial after all. (Which is great news, given the tendency of those in low-wage jobs to remain stuck there.)

In any event, it’s hard from the UK statistics to see either of our great fears being borne out. Jobs aren’t vanishing. And the middle isn’t being hollowed out – if anything, it’s thickening.

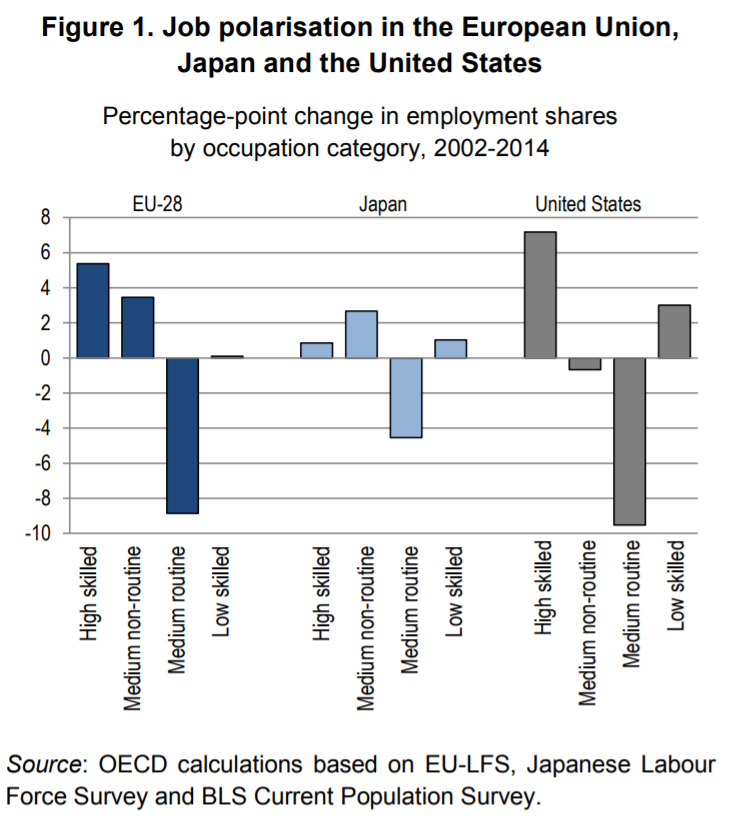

One possible answer comes from the OECD. In America, its figures suggest, the hollowing out really is happening: the proportion of high-skill and low-skill positions is growing, and those in the middle are shrinking.

But in Europe and Japan, the picture is different. The kind of jobs the OECD refers to as “medium routine” – ie the most automatable – are indeed evaporating. Yet the proportion of “medium non-routine” jobs – those involving working with new information, solving problems, or dealing with people – is rising.

The labour market, in other words, isn’t simple. It’s changing in different ways in different places, and for the good as well as bad. Yes, the great hollowing out may still happen. But if nothing else, these statistics are a reminder that we are still just as good at creating new jobs as destroying them. Rather better, in fact.

This article is taken from CapX’s Weekly Briefing email. Subscribe here.