The past six years have seen the old rules of British politics torn up. Identities such as ‘Tory’, ‘Labour’, ‘working class’ or ‘middle class’ have been replaced by ‘Remainer’ or ‘Brexiteer’ and voters are deserting their traditional parties.

The Conservatives, once the party of choice for middle-class professionals, increasingly dominate among working-class voters in what used to be Labour strongholds. Labour, meanwhile, has become a party for young professionals and university graduates. Its position as the dominant party in industrial England, and virtually all of Scotland and Wales, has been challenged or usurped entirely.

In our new book, Religion and Euroscepticism in Brexit Britain, we show how this realignment of British politics is also transforming the ‘religious vote’. The same changes to the British electorate that helped deliver Brexit are also changing the the historic links between Britain’s largest Christian communities and the political parties. Labour’s Catholic vote has collapsed, while the Conservatives are increasingly the party of choice for Christians.

The tumult stems largely from longer-term change in the ideological priorities of the electorate. Issues relating to national identity, ethnicity, cultural change and migration have become more important and the result has been starker divides between socially liberal people and social conservatives. The 2016 EU referendum and the 2017 and 2019 general elections divided voters into those who were pro-EU, pro-migration and pro-cultural change and those who were eurosceptic, socially conservative and held to traditional conceptions of national identity. These divisions continue to shape party support and attitudes towards issues such as the UK/EU relationship, climate change and the government’s response to COVID-19.

The religious vote

Britain’s Christian communities have long tended to support one of the major parties over the other, largely as a result of historical ties and the tendency for families to pass their political allegiances down from one generation to the next.

Anglicans and Presbyterians, as members of the national churches of England and Scotland, have tended to support the Conservatives as the party that represented ‘the establishment’ (of which those churches are a part). This is so much the case that the Church of England has been known as ‘the Conservative Party at prayer’.

Catholics and nonconformists (such as Methodists), on the other hand, were historically persecuted by the Church of England and the British state. They have tended to support radical, anti-establishment parties such as the Liberals and, more recently, Labour. Many British Catholics also descend from Irish migrants with roots in the trade union movement, and hence have stronger ties to Labour.

But the tendency of most Christians to be typically more socially conservative than non-religious voters has meant that their voting behaviour has been acutely affected by the rising importance of social conservatism and the ‘culture wars’.

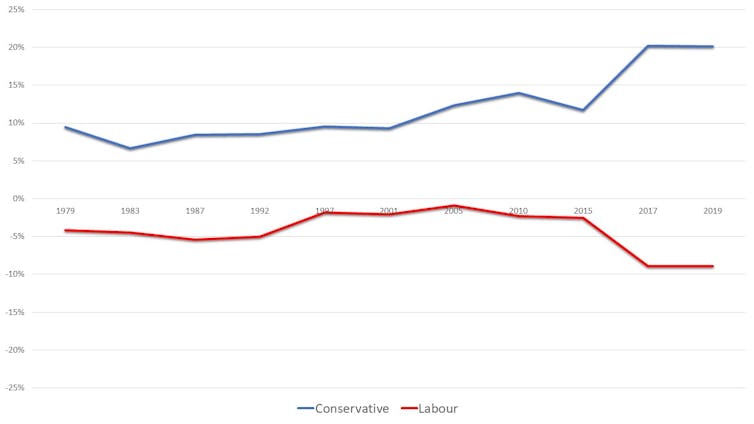

The Anglican vote

Support for the Conservatives among Anglicans and Presbyterians has grown significantly since 1979. Among Anglicans, support for the Tories was, on average, ten points higher than the party’s support in the wider electorate between 1979 and 2001. Even in 1997 and 2001, two of the worst results of the last century for the Conservatives, support among Anglicans was nine points higher than in the electorate.

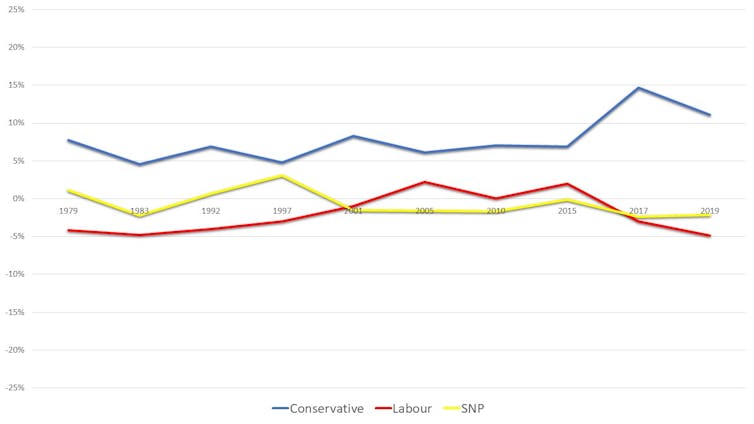

After 2005, this ‘Anglican boost’ started to grow, reaching 13 points by 2015 and 20 points in 2017 and 2019. A similar (though less pronounced) pattern is clear in Scotland among Presbyterians, with the ‘Tory boost’ growing from an average of six points between 1979 and 2015 to 13 points in 2017 and 2019.

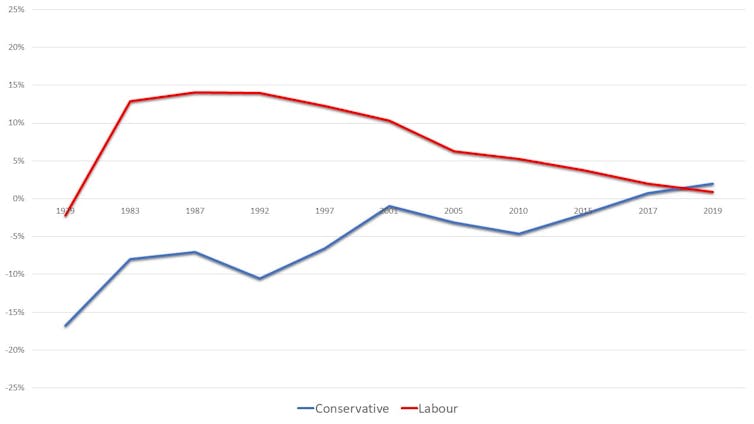

The Catholic vote

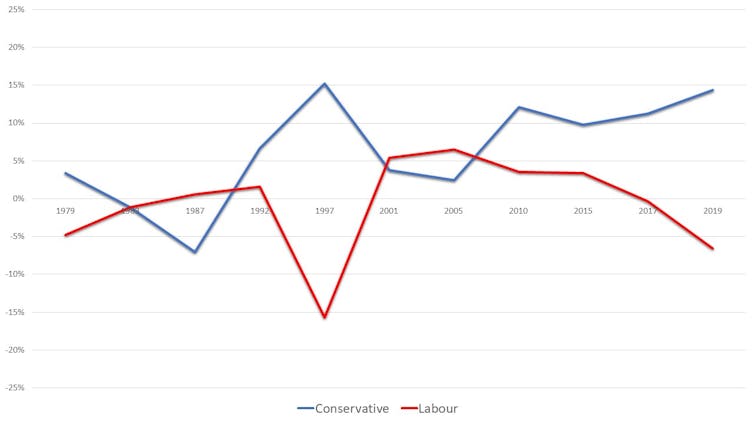

More remarkable still is that Conservative support has grown among those communities that have historically opposed the party. In 1979, support for Tories among Catholics was 17 points lower than that of the wider electorate. Over the following 40 years the ‘anti-Tory’ sentiment eroded to such an extent that by 2019 Catholic support for the Tories was two points higher than in the wider electorate. A similar, though weaker, trend is apparent among Methodists, among whom Tory support was three points higher than the wider electorate between 1979 and 2001, but then increased to an average of 13 points by 2017 and 2019.

Catholics leave Labour

The loser from this change is the Labour Party. In the 1980s, Catholic support for Labour was around 13 points higher than in the wider electorate (even during the party’s 1983 disaster). By 2019, Catholics were no more likely to vote Labour than non-Catholics. Methodists are also moving away from Labour, with their support for the party seven points lower than in the wider electorate in 2019.

The Presbyterian vote

Anglicans have never been particularly likely to support Labour, but they are becoming even less likely to do so as their support for the Tories grows. In 2019, Labour’s support among Anglicans was nine points lower than the wider electorate. Perhaps the only good news for the party (relatively speaking) is that in Scotland, where Labour has neither enjoyed a boost nor faced a penalty among Presbyterians, the situation has not deteriorated.

There are many distinctions between the theological beliefs and historic experiences of Britain’s Christian communities but they share a tendency to be more socially conservative than non-religious voters. And as Boris Johnson’s Conservatives position themselves as the protectors of these social values, even more Christians are likely to end up beyond the electoral reach of the Labour party. It will be a struggle to win over socially conservative “red wall” voters without alienating the (far more liberal) youth vote.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.