This piece was originally published on the Centre for Policy Studies’ new monthly newsletter, which you can sign up to here.

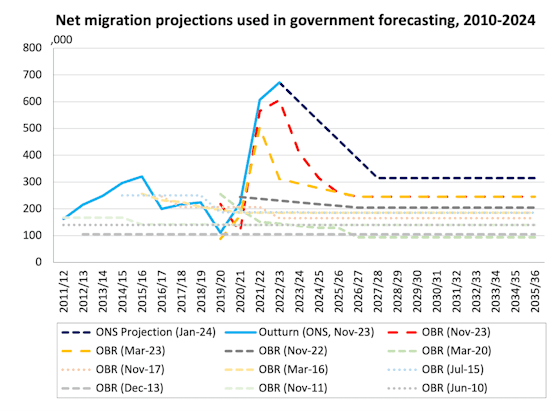

Since the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) was founded in 2010, the net migration projection informing economic modelling at each Budget has, compared to reality, fallen short by an average of 23% in the first year of the forecast, and 36% by the fifth year of the forecast. Yet it is partly on the back of such projections – taken from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) – that Chancellors’ tax and spend decisions have been made for the last 14 years.

As an issue, this has come to the fore because while net migration has surged to unsustainable levels (672,000 in the year to June 2023), official estimates and projections keep falling woefully short.

At the same time, the ‘long-run rate’ at which annual net migration is projected to settle keeps rising. In the most recent ONS population projections, which should feed into the modelling for this March’s Budget, that figure was revised up to 315,000. A decade ago, in the March 2014 Budget, that number was assumed to be 105,000 – exactly a third of where we’re thought to be heading now.

I have looked at why net migration projections are important for economic and fiscal policy making before, notably on CapX and for the Spectator, and in relation to the housing crisis for the Centre for Policy Studies. If we can’t get migration-driven population growth projections right, then we can’t anticipate future needs in terms of housing, school places, healthcare spending, the state pension and so on. Net migration added around 1.9% to the UK’s population in the two years to June 2023 – over 1.2 million people in the space of just two years.

The discrepancies between the projections and the actual numbers have become particularly stark since 2021 (although to be fair, the ONS and OBR are doing a lot of very good work to try to improve the quality and timeliness of the data). But having gone back through all 27 OBR editions of the OBR’s ‘Economic and fiscal outlook’ (EFO) to 2010, and ONS population projections back to 2008, it’s clear to me that the last two years are not really an aberration.

In fact, the net migration projections used in OBR modelling have been consistently and significantly wrong since its foundation – as the graph below shows.

Rather than charting net migration assumptions used in every EFO, I have elected to display just those where the assumptions were changed. But in the underlying analysis, I have looked at every single one.

We have provisional net migration numbers up to 2022/23 from the ONS (although these are likely to be revised upwards in the May 2024 data release). This means we can compare the projections for each individual year in each individual EFO projection with the outturn up to and including 2022/23.

This analysis shows that across 180 data points, the net migration outturn was less than the projected number on just 29 occasions, and the Covid year of 2019/20 accounts for more than half of these. Excluding 2019/20, the outturn has exceeded the projection 93% of the time.

There are lots of grounds for criticising how net migration figures are used in official policy making, including lack of coordination across government, asymmetric modelling of costs and benefits, implausible labour force participation assumptions, the focus on GDP rather than GDP per capita, and the treatment of all migrants as essentially fungible economic units (in reality, studies show that migrants from some countries are much more likely to be net economic and fiscal contributors than others).

However, the most fundamental criticism is surely that the projections are so often wrong, by such a significant amount. But it would be unfair to attach much of the blame to the OBR or ONS for this. Arguably the fallibility of net migration projections simply reflects a reality in which we have lost control of our borders.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.