Progress on eliminating poverty has been rapid in recent times. Over three decades, the rate of extreme poverty in the developing world has fallen from more than one out of every two people to roughly one out of every five, according to the World Bank. This astonishing – and very welcome – reduction in extreme poverty represents the single greatest decrease in material human deprivation in history.

This is largely a result of expanding free trade and – to a great extent – the freedom of capital movements that have led to increased private investment. These benefits are particularly obvious in China; the President of the World Bank, Jim Yong Kim, claims that 700 million people have been lifted out of poverty as a result of trade and the opening up of China’s economy to competition.

However, the link between overseas aid and poverty alleviation is far less conclusive. For example, Angus Deaton – winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2015 – concludes that overseas aid ultimately does more harm than good.

Of course, specific overseas aid programmes can help lift people out of poverty, but the efficacy of them is often highly questionable. Even the UK’s Department for International Development (Dfid) – which, incidentally, is one of the most effective departments of its kind – faces significant challenges with many of its bilateral programmes. This includes worrying reports of fraud and the excessive use of western-based consultants.

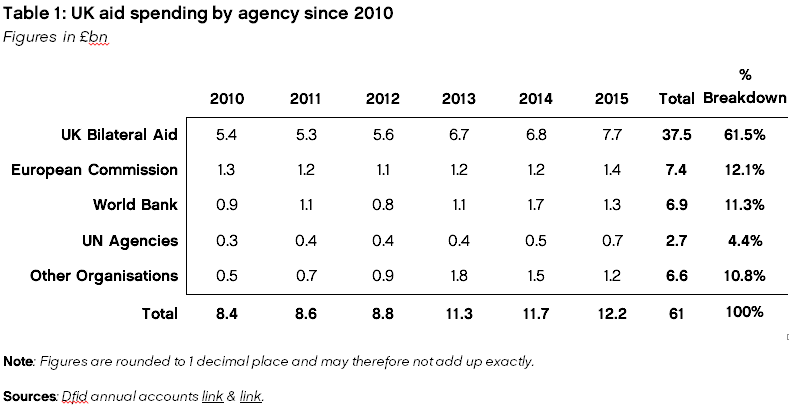

The UK gives around a third of its aid budget to various multilateral bodies, which are often even less effective at spending overseas aid. The Independent Commission for Aid Impact recently warned that Dfid’s increasing reliance on these partners has risked those relationships becoming “too big to fail”.

There are particular concerns about the £7.4 billion of UK funds that have been given to the European Commission (EC) since 2010. The EC’s administration costs are notably higher than Dfid’s and a House of Lords Committee has reported that the majority of resources are not targeted at the poorest countries. Moreover, Dfid’s influence on the delivery of EC aid is very limited despite contributing around one seventh of the budget.

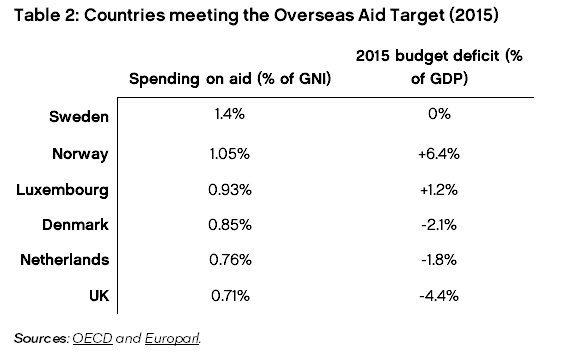

Our annual target of spending 0.7 per cent of GNI on overseas aid is adding to these problems. When legislation to impose the arbitrary percentage reached the House of Lords, many Peers expressed concerns.

The fiscal impact is certainly an issue. There are only five other countries meeting the target and – on average – these nations ran a budget surplus in 2015, whereas the UK ran a substantial budget deficit of 4.4 per cent of GDP.

But even setting aside the fiscal implications, there have been other significantly worrying trends associated with the target. A recent investigation by The Times revealed that the UK is dumping billions of pounds in World Bank trust funds in order to reach it. At least £9 billion has been put into 219 different World Bank trusts over the past five years for this purpose. This is more than any country apart from the United States and follows a previous report by the National Audit Office of Dfid rushing spending towards the end of a financial year.

And oral evidence submitted to the International Development Committee reveals that the biggest aid contractors are now receiving more cash from Dfid. Five hundred million pounds went to the 11 largest contractors in 2015, which was double the amount they received two years previously.

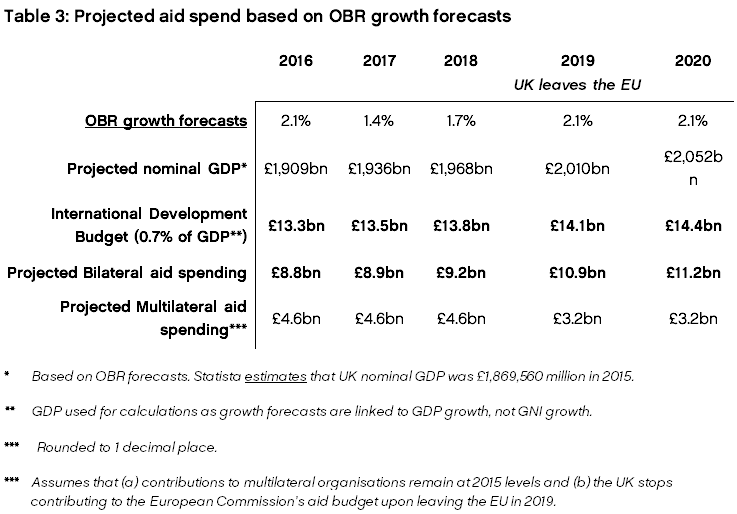

It is obviously very concerning that all of this involves taxpayers’ money. However, as today’s Centre for Policy Studies report, Time for a Dfid Diet?, suggests, Brexit does provide an opportunity for a wholesale re-think of the UK’s aid policy. In particular, the UK now has the chance to reclaim its £1.4 billion annual contribution to the EC’s aid budget, which it currently has little influence over.

Of course, this is good in one sense. Evidence suggests that Dfid might be more effective at spending the aid money.

However, if all the cash were simply transferred to Dfid’s bilateral budget, many of the problems with the UK’s aid programmes would undoubtedly become more pronounced. The budget would grow by a massive 18 per cent in one year, and all of the waste associated with some of the UK’s aid programmes and, more specifically, the 0.7 per cent target would be exacerbated.

While the Government’s direction on overseas aid policy is generally encouraging, particularly the push for greater scrutiny, sticking to the arbitrary 0.7 per cent spending target is a mistake.

Aid is often ineffectively distributed, spending is rushed and a huge jump in Dfid’s bilateral budget post-Brexit could make things worse. The Government needs to grasp the nettle and review that 0.7 target while it has the chance.

Time for a Dfid Diet, is published today by the CPS