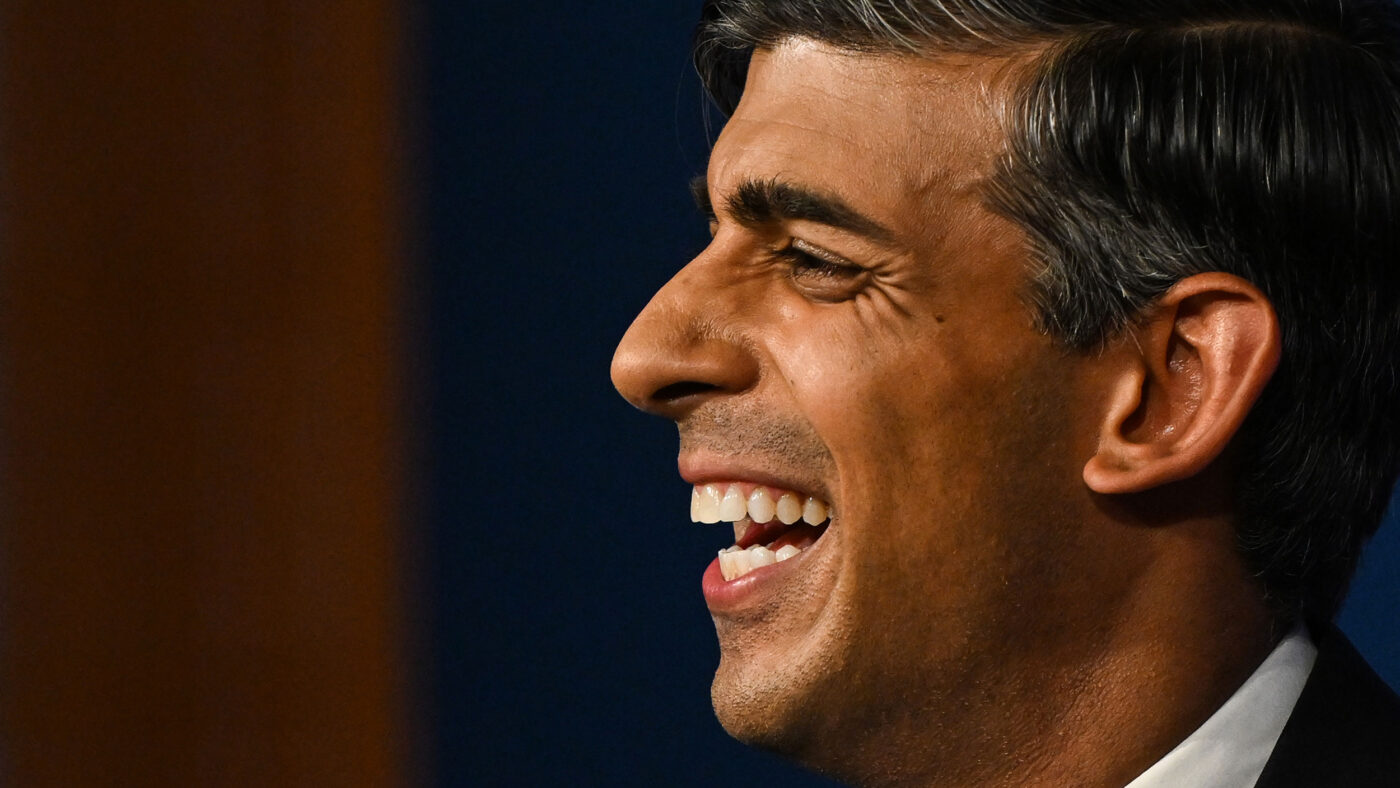

More clarity, more scrutiny, more long-term thinking – Rishi Sunak’s attempt to inject some realism into the Net Zero debate is a welcome development. But in his Downing Street address yesterday, he did not entirely escape the wishful thinking and cakeism which have characterised UK energy policy since the Climate Change Act of 2008.

Certainly he was right to point out that we have ‘stumbled into a consensus’. Indeed, Net Zero 2050 is probably the single most expensive policy commitment made by a British government since declaring war on Nazi Germany in 1939 (though it’s so open ended, it could end up costing a lot more than that).

It came about not through reasoned debate about the costs, trade-offs and priorities entailed, but rather as a sop to Theresa May – a substitute legacy for the Prime Minister who failed to deliver Brexit. It was waved through by MPs, and with the country distracted by Brexit, it received virtually no scrutiny at the time.

In particular, we did not have the debate we should have had about what is commonly called the ‘energy trilemma’ – the tensions between decarbonisation, energy security and energy affordability. As we saw with the creation of the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero earlier this year, Sunak is clearly more alert to these difficulties.

His decision to push back intermediate targets on banning new gas boilers and the sale of petrol and diesel cars followed a similar logic, being mostly couched in cost of living terms. But there is also a deeper issue he did not mention directly: the grid simply might not be able to cope with the additional electricity demand generated by electric vehicles by 2030.

The last of our coal-fired power generation capacity will be gone within a year. We’re set to decommission 5.3GW of nuclear capacity by 2028. On the current trajectory, nameplate renewable capacity is going to be 38% short of government targets by 2030, and the outlook is not improving: witness Vattenfall’s decision to call off its offshore wind project due to rising costs. As Dieter Helm has noted, current electrification plans, let alone Labour’s more ambitious targets, are deeply implausible.

There are other problems with the pace and trajectory of the UK’s energy transition. We might lock ourselves into suboptimal technologies through the state prematurely picking winners. And while Net Zero might eventually yield economic benefits, on the current pathway, most of the costs will be upfront. This is where the electoral politics of it all comes into play – as Robert Colvile has pointed out, voters love net zero until they actually have to start paying over the odds for it.

Sunak clearly gets this. Nevertheless, he still seems keen to square the circle, buying into the ‘huge opportunities in green industry’ narrative. Given the track record to date, there is certainly a whiff of cakeism about the economic benefits of the energy transition. In particular, politicians love to talk about jobs. But where for example are the green jobs promised in Boris Johnson’s ‘Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution’? This plan was supposed to support 90,000 jobs within this Parliament and 250,000 by 2030, but there is scant sign of them so far.

In fact, the ONS is developing metrics to estimate the size of the UK’s low carbon and renewable energy economy (LCREE). Provisional estimates show that the total number of full-time equivalent jobs in the green economy has increased by just 11,500 since 2014 (the earliest datapoint). That’s growth of 4.9% during a period when the number of people in employment increased by 5.3%.

But we also have to ask ourselves: for every green job being created, how many other jobs are being lost? The Port Talbot steelworks has been in the news recently because the Government is investing £500m of taxpayers’ money alongside £750m from Tata Steel to decommission the carbon-intensive blast furnaces at the site and replace them with greener electric arc furnaces, which will boost the ‘circular economy’ by recycling scrap steel. This will entail the loss of 3,000 jobs.

Aside from decarbonisation, the main justification for the move has been a strategic one: the UK needs primary steelmaking capacity for national security reasons. But as Tim Worstall notes, electric arc furnaces produce secondary steel, not primary steel, and secondary steel is not suited for all uses. Many military applications are ruled out, for example. But more pertinently, it cannot be used nuclear applications.

Given that the Government’s energy security strategy entails quadrupling the UK’s nuclear generation capacity to 24GW by 2050, and that Sunak confirmed that the next steps on small modular reactors (SMRs) will be announced this autumn, this is not exactly a sterling example of joined-up thinking. So much for capturing the economic benefits of the energy transition.

Additionally, switching the UK’s steelmaking capacity away from blast to electric arc furnaces puts a bit of a question mark over the Woodhouse Colliery, a planned metallurgical coal mine in Cumbria. The project was in fact ready to go in 2021, but was delayed to spare Alok Sharma embarrassment at COP26. In other words, more investment, economic growth, jobs, tax revenue and levelling up potential sacrificed on the altar of Net Zero.

And philosophical niggles aside, it’s because of episodes like this that we should be wary of calls for a UK industrial policy or strategy, even coming from otherwise very sensible people. We do have an industrial policy. It’s called Net Zero 2050. And in practice, it’s rather more of a deindustrialisation strategy.

Politicians like to boast that Britain has decarbonised further and faster than any other G20 country. And this is true. But it’s mostly because we’ve priced, taxed and regulated heavy industry into oblivion. Yes, China flooded global markets with cheap steel and so on. But with industrial electricity costs 50% higher than the OECD average thanks to policy choices, we didn’t do our manufacturing base any favours. So while ‘territorial emissions’ in the UK have fell by 42% between 1990 and 2019, ‘consumption emissions’ fell by 14%. Rather than eliminating emissions, we mostly just offshored them through import dependence.

Much of the argument for sprinting towards Net Zero has been couched in terms of the economic benefits arising from capturing first mover advantage – the early bird gets the worm. But there is another saying that seems more relevant in our case: the second mouse gets the cheese. Sometimes it is better to be a fast follower, benefiting from spillover effects, technological advances and movements down the cost curve.

Since at least Ed Miliband’s 2008 Climate Change Act, the UK has systematically underinvested in fossil fuels and nuclear, while taxing emissions. Windfall taxes have only intensified the problem. In particular, we missed out on shale gas production through fracking, and now rely on expensive, carbon-intensive imports to meet half of our gas needs.

The US green manufacturing boom is not simply a function of the vast subsidies unleashed by Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act. Thanks to the utterly transformative shale revolution, America industrial energy costs are a fraction of the UK’s. For energy intensive turbine manufacturers, electric battery gigafactories and hydrogen electrolysis (not to mention semiconductor fabs and chemical plants), this is a crucial consideration.

In contrast, in our drive to become the ‘Saudi Arabia of offshore wind’, we encouraged early investment in renewable energy generation at the top of the cost curve, with many of the levelized costs of energy stemming from intermittency and transmission costs ignored, downplayed or wished away through questionable modelling assumptions around load factors and perpetually ultra-low interest rates, for example.

The result of these policy choices is that Britain has the highest industrial energy prices in the OECD. Only Germany – another country that has sprinted towards Net Zero – comes close. This is a massive economic problem and one of the five main causes of low UK productivity growth, because energy is an input into just about all economic activity. And while we might make use of wind turbines, solar panels and batteries in electric vehicles, that doesn’t mean we can afford to make them here.

Sunak should fully level with the British people. We are neither the early bird nor the second mouse. We are the first mouse, and we have yet to extricate ourselves from the jaws of the Net Zero trap.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.