Ever since the EU referendum, Britain has become aware of the chasm running through its politics.

At first, people assumed that the split was simple: Leavers on one side, Remainers on the other. It was a division that particularly suited those among the elite who thought that Brexit was caused by stupid people being duped by bad people: they could simply be dismissed as “left behind” and “uneducated”.

In the wake of the recent election, it’s clear that this was wrong. On one side of the chasm are politicians of all colours, big business leaders, Brussels bureaucrats, senior civil servants, academics, commentators, and even trade union leaders. And on the other are all those who feel cut off and left out by those in charge. And what has placed them on that side of the divide is not Brexit, but a desire for change.

Responsibility for causing that massive divide can’t be shirked by those who control or influence what happens to everyone else but who never or rarely cross over to find out what it’s like on the other side, to discuss with the people there what’s wrong and how they too can play a part in putting it right.

Right now, there is much criticism of Theresa May. A lot is justified. But her ambition and strategy was right: to build a bridge to those cut off. And if the Conservatives as a party, and Britain as a country, want to recover from the worrying place where we now find ourselves – especially as Brexit negotiations begin – it’s important to work out what went wrong.

Alone among senior politicians, Mrs May seemed to understand that the only way forward after the referendum was to get over to the other side – to listen and learn. And once over there, to address the concerns of one group in particular.

The people whom Mrs May called the “just about managing” had been talked of often, but had not been properly understood for a very long time. They lived alongside many who were poorer and in many ways more desperate or more directly discriminated against – and whom politicians would speak up for. But for those doing ordinary jobs well, modestly successful in their field, and trying to be good citizens, it was pretty galling to be forever ignored, to be never asked for advice on how things might be improved.

When Mrs May arrived, they could not believe it. Finally, they had a spokesman who really did seem to understand what they were all about. (Even though she had sacked me from Cabinet on her arrival as Prime Minister, I was excited on their behalf, because she talked as if things really were going to change.)

At this point, Mrs May was the most popular politician in the UK. She was also seen far more favourably by C2DE voters (Labour’s traditional support base) than Jeremy Corbyn, at 44 per cent to 27 cent. This gap was not just about class – which is no longer a very good indicator of voting intention – but education. In the EU referendum, nearly two thirds of post-graduates and four in five of those still in full-time education voted to Remain, against 64 per cent of those whose formal education had ended at secondary school voting to Leave.

Throw forward to the general election results, and the earlier voters had left full-time education, the more likely they were to vote Conservative. (Of those with only GCSEs or below more than half voted Conservative, compared with a third who voted Labour. At A-level it was 45 per cent Conservative, 40 per cent Labour. Only when voters had degrees were they more likely to vote Labour: 49 per cent to 32 per cent.)

This educational divide interests me a lot, not least because of my own unconventional route to the Cabinet: two A-Levels and excellent secretarial qualifications. Now that it is rarer than ever for anyone to get to the top without a degree, the divide between those who are university-educated and those who aren’t feels even worse, because those cut off also have to battle the misconceptions of those with degrees.

If a large chunk of Mrs May’s “just about managing” cohort are non-graduates (and all the evidence suggests they are), everything she was saying sounded like they were finally being taken seriously – not because they were poor or down-trodden, but because they were people who had something to contribute.

In Mrs May’s various statements and speeches (especially her first on the steps of No 10), she told those who had long felt ignored that she understood that voting Brexit wasn’t that much about Europe: it was their way of being heard. And on this front, there was no one better placed than the Prime Minister to lead the charge.

What was so frustrating was what happened next. Only a handful of influential people followed Mrs May across the chasm: most chose instead to stand on their own side of saying Brexit was all so difficult and those who’d voted for it had no idea just how difficult.

And as pleased as the cut-off were to have the Prime Minister on their side, their confidence in her was fragile. Mrs May is a Tory, after all, and a huge number of them are not natural Conservative voters.

To reassure her new friends, Mrs May had no choice but do what she did next: turn her back on her those “in charge”. Sadly, those in charge did nothing but look on in horror. Not only did Mrs May not explain what was happening, she started calling them names, the worst being the really insulting and hurtful “citizens of nowhere”.

To them Mrs May was not taking a lead: she had “surrendered” to the Brexiteers. And it seemed even worse than that. One minute she was moving to the Right and swallowing UKIP’s agenda. The next she was shifting to the Left, proposing workers on boards and caps to energy prices. They couldn’t work out which way she was going and assumed eventually she would retreat to a more sensible place.

You’d think sophisticated and educated people could suck up a bit of name-calling and would be smart enough to work out for themselves what she was doing – and why they needed to give her the benefit of the doubt. But Mrs May – as their Prime Minister too – should have realised they also needed leadership from her. In fact, she owed it to those people who were desperate for things to change to get as many powerful and influential people on board as she could.

Then came the whole kerfuffle over Article 50. The voters for whom so much rides on Brexit happening weren’t bothered by the detail, but there was frustration and anger at know-it-all politicians trying to give themselves the power to overturn the referendum result. Of course, Parliament has to be involved in the Brexit process. But parliamentarians needed to embrace the fact that we are leaving the EU, not just accept it with the illest of grace.

Voters very rarely hear what politicians say, but they notice what they do and the way they behave. Instead of those with all the power for coming up with a plan for Brexit, they saw more of the same – and worse. They kept hearing politicians and others say they had been duped. They saw Tony Blair re-emerge on the warpath – though it wasn’t quite clear to where.

So – out of the blue – Mrs May called a general election. And most people thought she was right to do so. (The decision was backed 49 per cent to 17 per cent, with 34 per cent “don’t know”).

At that moment, to the voters who desperately wanted change and saw Brexit as their vehicle to it, Mrs May really was their only hope. This was serious. She was serious.

But this is where that great misunderstanding about the nature of the chasm comes in. The Tories thought – everyone thought – it was about Brexit. So the decision was taken to make the campaign all about Theresa May and her being strong and stable on the issue. Not least because it was recognised that it was her and not the party as a whole who was driving non-Tories towards them.

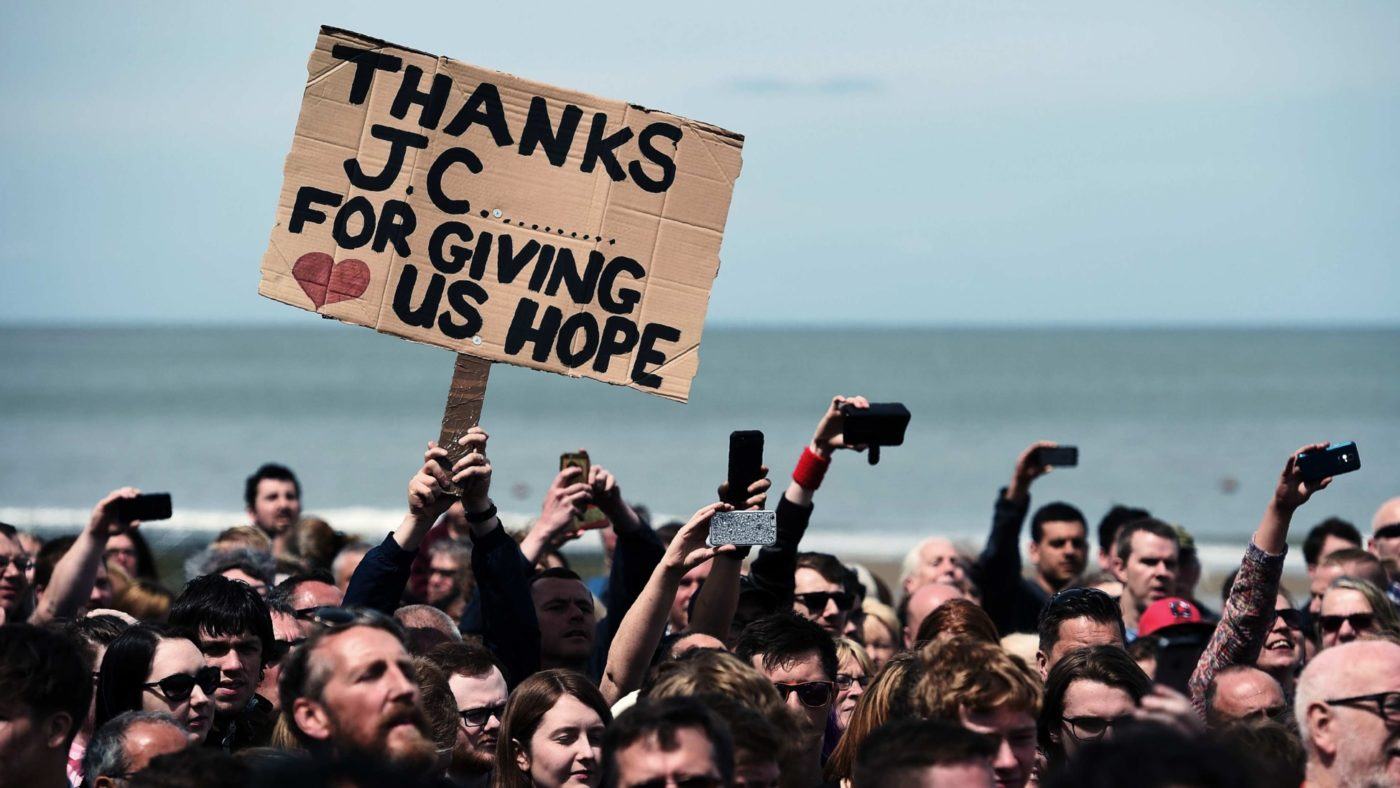

But what no one had noticed – or maybe they had forgotten – was that another politician had been on the “wrong” side of the chasm, long before Mrs May had arrived. True, Jeremy Corbyn had only mixed with a relatively small sub-section of voters. But while everyone had been ignoring him, he and his team had been doing a lot of listening to what people said about what was wrong and working to come up with a plan.

And what a plan it was. Their manifesto contained some weird and wonderful ideas such as more bank holidays, new Trident missiles that would never be used, the renationalisation of several industries. And there was no way everything could be implemented without higher taxes and an even bigger deficit.

But the stuff in there had come from discussions with real people. It’s not surprising then that a lot of it was attractive to many voters – especially to the young and those with young families, for whom optimism and hope is currently in such short supply. His core graduate vote got promises to abolish tuition fees and forgive student debt. Public servants fed up with year after year of pay squeezes wanted and needed to hear that something else was possible.

On top of that, Jeremy Corbyn looked like he enjoyed being with and talking to people about his ideas. He seemed less interested in being their leader, more of a spokesman. The result was that two thirds of 18-24 year olds voted Labour. And Labour attracted the majority of voters in all age groups under 50.

Let’s not get too carried away, here. Jeremy Corbyn and his style of politics were not received enthusiastically by everyone, even among those who were interested to hear what he had to say.

There are a lot of people among the cut-off for whom Corbyn is not their sort and never will be. Older voters, Labour and Conservative alike, were not attracted to McDonnell’s style of economics because they’d lived through it and just about survived it before. Many could not put to one side the sympathy Corbyn had shown to the IRA’s cause while it had been bombing British citizens; or his and McDonnell’s associations with hard-left and violent groups. And for many voters, while Labour’s manifesto contained interesting ideas, the economy and jobs still ranked among their top priorities – and their negative view of Corbyn and his team on those issues had not changed.

In short, the Labour manifesto was an agenda for change and together with their campaign, highlighted the fact that, so far, Mrs May had not really done anything concrete for the “just about managing”. But the Prime Minister had understood and adopted people’s desire for change, and had already shown her mettle on their behalf in the Article 50 wrangling. They were confident she was there to fight for them and to stand up to others, but she would need to put her money where her mouth was, so-to-speak.

And that’s why Mrs May’s manifesto was such a disaster. Social care, scrapping universal cold-weather payments, the pension triple-lock and free school meals… even before you got to the revival of fox-hunting, this was not what they had signed up to. They didn’t mind what kind of Brexit she negotiated, and they appreciated her frank and honest account of the challenges ahead. But they did not want – yet again – to be the ones who had to pay for it.

If you read the manifesto from cover-to-cover, you do get a sense of the kind of country Mrs May wants to lead. And it does chime with what she had been saying in the previous few months. But it wasn’t a call to arms for all those who had been so inspired by her arrival 10 months before. The manifesto should have been her way of showing how the Conservatives would take them and their contribution seriously and how they would prosper more fairly from doing so. Instead, it gave them little hope that anything would change.

And when everyone kicked off and Mrs May U-turned on social care but tried to say she hadn’t, people were no longer sure whose side she was on, because she didn’t seem sure herself. From then on, the more pressure Mrs May faced, the more she retreated. At the very moment they needed her to be strong and stable, she wasn’t.

After such a strong start to her premiership – and one of the most powerful speeches made from an incoming prime minister – it is hard to understand how and why Theresa May and the Conservatives got this campaign so badly wrong. The biggest complaint from her colleagues is that Mrs May and her close-knit team never talked to them. From the manifesto, it seemed like they hadn’t talked to anyone else, either.

Yet perhaps their biggest mistake – and the strangest, bearing in mind everything they had done up to this point – was to assume that because their primary target were non-Tory Leavers, this was a Brexit Election.

As all the evidence shows, voters supported leaving the EU as a means to an end, not an end in itself. They thought it would improve their living standards and access to benefits and public services by ending the economic and social competition from migrants.

When Corbyn came along promising free tuition, an end to public sector pay freezes, more money for public services, and a whole raft of polices aimed at the less well off, they responded as they had done to Vote Leave’s £350 million a week for the NHS: they knew they were not going to get everything on the menu, but at least the restaurant was offering the kind of food they wanted to eat.

In the end, it was an austerity election among those for whom it was supposed to be a Brexit Election, and a Brexit Election for those who were supposed to see it as a referendum on seven years of Tory economic management.

Labour did not, of course, win. In fact, the Conservative Party received its highest share of the vote since 1983. But Corbyn’s unexpected success, against all expectations, has changed the debate about the way forward.

The fundamental problem, however, remains the same. There is a massive gap between those who feel cut-off and those who hold all the power and influence. Mrs May did not get the clarity of a strong mandate to implement her manifesto. But the voters could not be clearer that the gap between “them” and “us” has to close. The tragedy at Grenfell Tower has shown just how serious this divide is.

So what is the way forward from here?

We should always remember that politics is less about politicians and more about the voters, so my general advice to Mrs May is this. It doesn’t matter how much longer you remain in post. You are the Prime Minister, and the same people – and many more – who were relieved to see you cross that metaphorical divide last July now need you to do it for real, and to do it urgently. And this time, you need to take other people with you who can help – including big business figures.

Politicians and business leaders need to stop using complexity as an excuse for inaction. Recognise that for citizens, Brexit is a means to change – and even those who didn’t vote for it desperately want things to be different. Of course, people recognise there are no simple solutions but what they are looking for is evidence of some simple, honest, motives amongst those in charge. (‘Motive’, incidentally, ranked first among all voters in determining who they voted for.)

By all means debate amongst yourselves the best way to do it, but you have to communicate to your voters, workers and customers what outcome you are seeking. Think more water and less tap. Once people are confident of why a particular route is being argued for and that they too will get some benefit from it, they will relax.

It’s clear that yet more pay freezes and diminished public services cannot be tolerated. But if Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell seem like the only ones with answers, it will feel like a betrayal to all those who know from experience that there is a better way.

Last year’s referendum, and this year’s election, have shed light on the big divides emerging between the old and young, graduates and non-graduates. Over half of today’s young adults are not educated to degree level – and hardly any of them will be found, in future, among those in charge. In the past, non-graduates were taken more seriously. We need to start taking them seriously again and encouraging them by opening up more opportunities.

Of course, we must not allow young and old to be pitched against each other. And suggesting, as many policy-makers and commentators do, that young people are fed up with not having access to the benefits their parents could rely on is not a good enough answer, not least because it diminishes the accomplishments of anyone over 50 who has struggled to succeed.

The Conservatives, and everyone else who can see the dangers of a Corbyn- and McDonnell-led administration, have got to find a way to mobilise the vast majority who – over the last 30 or 40 years – have grafted hard for what they’ve achieved. Some will have battled and won their way through austerity, 1970s style. Set up small businesses. Been made redundant in the 80s and possibly again in the 90s and know full well what went wrong and how things could be put right if only we bothered to ask.

Many of them know why socialism isn’t the answer and will fight against it.

But they need a new form of capitalism to campaign for – one which means that young people get a chance to succeed on their own terms too.

Theories and metaphors are not good enough. Those cut off from power need politicians – and bosses and everyone else on the other side – to stop asking them to be the only ones who pay. They need the people in charge to get over to where they are and work together with them in putting things right.