The IFS Green Budget is, as ever, a treasure trove of ideas and data – far too many to address in one article. Predictions of unemployment rising to 5.8% next year – the highest for a decade. Estimates of how much this government’s tax threshold freezes will raise – some £52bn by 2027-28. And discussion of the potential inflationary impacts of any near-term tax cuts.

One lens through which much of it can be understood, however, is its discussion of the government’s ‘fiscal mandate’: that government debt should be falling as a share of national income between years four and five of the forecast period. It rightly notes that, although all fiscal rules have weaknesses, this is a particularly easy one for policymakers to game. It’s fine if government debt doubles as a share of GDP during the first four years of any forecast period, provided only that it is scheduled to drop in the final year. And that on the basis of mañana promises of action that the incumbent chancellor almost never has to implement (since only three chancellors since 1979 have lasted more than 5 years anyway).

In the run-up to the UK’s fiscal consolidation of 2010 onwards I wrote a fairly widely discussed study of major fiscal consolidations that had occurred in the past in the UK and internationally (Controlling Spending and Government Deficits: Lessons from History and International Experience). One key lesson I drew was as follows:

‘During periods of significant cutting, fiscal rules have limited, if any, role compared to a ‘just do it’ culture. By contrast, institutional mechanisms — specifically, constraints such as an IMF intervention or EU rules — often do have a role. Once spending is down and a low spending culture is achieved, rules or mechanisms may be useful expressions of a culture (though never a substitute for it).’

The fundamental problem with the fiscal plans of Jeremy Hunt and Rishi Sunak isn’t the details of their rules. It’s that they themselves have no genuine will to get spending or the deficit down and, if they lose next year’s general election, none of the serious work of deficit reduction is going to be their problem anyway. If you want to cut the deficit, cut the deficit. Don’t announce yet another rule that declares the deficit will be cut this year, next year, some time, never.

The Green Budget talks in terms of significant further tax rises being inevitable. But in my view it is too optimistic (if that’s the word) about the UK economy’s ability actually to generate as much extra tax as Hunt schedules at present, let alone even more.

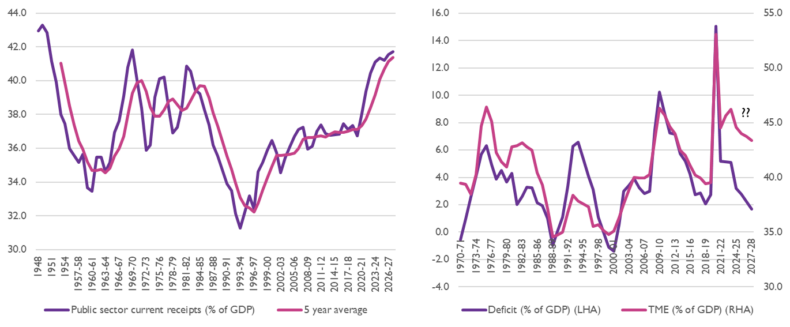

UK Tax receipts, debt and public spending (Total Managed Expenditure – TME)

.

In individual years in the past (specifically in the early 1960s), the UK economy managed to generate roughly the same amount of tax, relative to national income, as it is scheduled to do under Hunt’s plans. But it has never managed above 40% on average over time (say, a five year period) since the period of demobilisation just after World War II. Yet Hunt’s plans require it to generate nearly 41.5% by 2027/28. It is very doubtful whether that is possible. More likely is that the attempt to set taxes so high drives the economy into recession and the tax take falls back.

On the other side of the ledger, contra the impression one might have from listening to the IFS, the rise in spending we have had is not the result of some underlying long-term demographic process of an ageing population with higher spending needs. The rise happened very quickly. In 2019 we were spending 39.5% of GDP. This year we are spending over 46%. That’s a 17% rise in the role of the state in just a few years. It is the result of political choices, not underlying demographics. Under Hunt’s plans those political choices extend off to the horizon, with spending scheduled to be well over 43% even in 2027/28. Moreover, that is, of course, if one believes that Hunt would implement the spending cuts he’s scheduled for after next year’s general election, let alone believing that Labour would actually implement them once it won.

With spending unlikely to fall below 45% of GDP, taxes unlikely to rise above 40% of GDP, and government debt interest rates of 4-5%, if inflation were to continue to be targeted at 2% over the longer term then GDP would need to be growing at getting on for 3% per year for the debt to GDP ratio not to spiral ever upwards, rapidly driving us into sovereign insolvency. Perhaps some kind of technology shift might deliver that – AI, driverless cars, green tech, lab-grown meat and cancer vaccines could all make big differences. But relying on that is a fiscal hail Mary. As things stand the more likely path for growth is that 1-1.5% is the best we can rely upon. Truss tried to change that, but politics absolutely prevented it.

So for debts to stabilise, given that the IFS’ prescription of higher taxes is unlikely to be deliverable even if it were desirable (which, to be clear, it is not), we either need spending to fall – which is what will happen in the end if we enter fiscal insolvency and the IMF or some similar body takes control of our spending, as happened in the 1970s – or we need systematically higher inflation over the medium term (say, 3-4% instead of 2%). Which are you betting on?

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.