Living on our planet is more enjoyable than it used to be in almost all respects. We live longer, we are healthier, we learn more, and we enjoy greater comfort. The one exception is what we see. From the Stone Age to St Mark’s Square, human beings spent millennia learning to make more beautiful things. In the twentieth century, suddenly, we stopped. This summer was a reminder, as RIBA gave its National Award to a Richard Rogers development on the Wandsworth riverbank resembling giant steel fangs emerging from a pavement.

But the establishment fell in love with ugliness just as governments became more committed than ever to our ‘wellbeing’: just not, apparently, when we are looking at things. Our politics doesn’t notice the things we notice. So why did beauty cease to be a public good?

Over the last century, our Establishment has gradually become not just ambivalent about beauty, but engaged in destroying it.

That modernist reaction – the downward-levelling of beauty – which went hand in hand with the rise of socialist thought, began precisely because the elite possessed the most beautiful things. The Bauhaus movement that exploded in the 1930s instead made ‘people’s architecture’, mass-produced box-forms intending to create ubiquity across nations. In the Postwar years, the cultural march through the institutions also had an aesthetic outcome: if local style connected people to their past and to local identity, destroying it could rid them of this false consciousness.

But the result was classically socialist. As beauty grew rarer, it became more expensive, and like food in a regime of collective farms, was soon monopolised by the elite. The poor got tower blocks: the rich kept Chelsea.

As the counter-culture became the Establishment from the 1960s onward, the subversion of tradition became the very raison d’etre of architecture, a drolly predictable convention. If beauty was just a social construct, it could quickly be deconstructed: like Red Guards at war with the Four Olds, modernism launched its assault on our deep sense of what is beautiful. But it didn’t work. Like the classical architects who mastered proportion and line, we hold in the heart an innate sense of what is beautiful. Our architects forgot beauty, but our instincts did not.

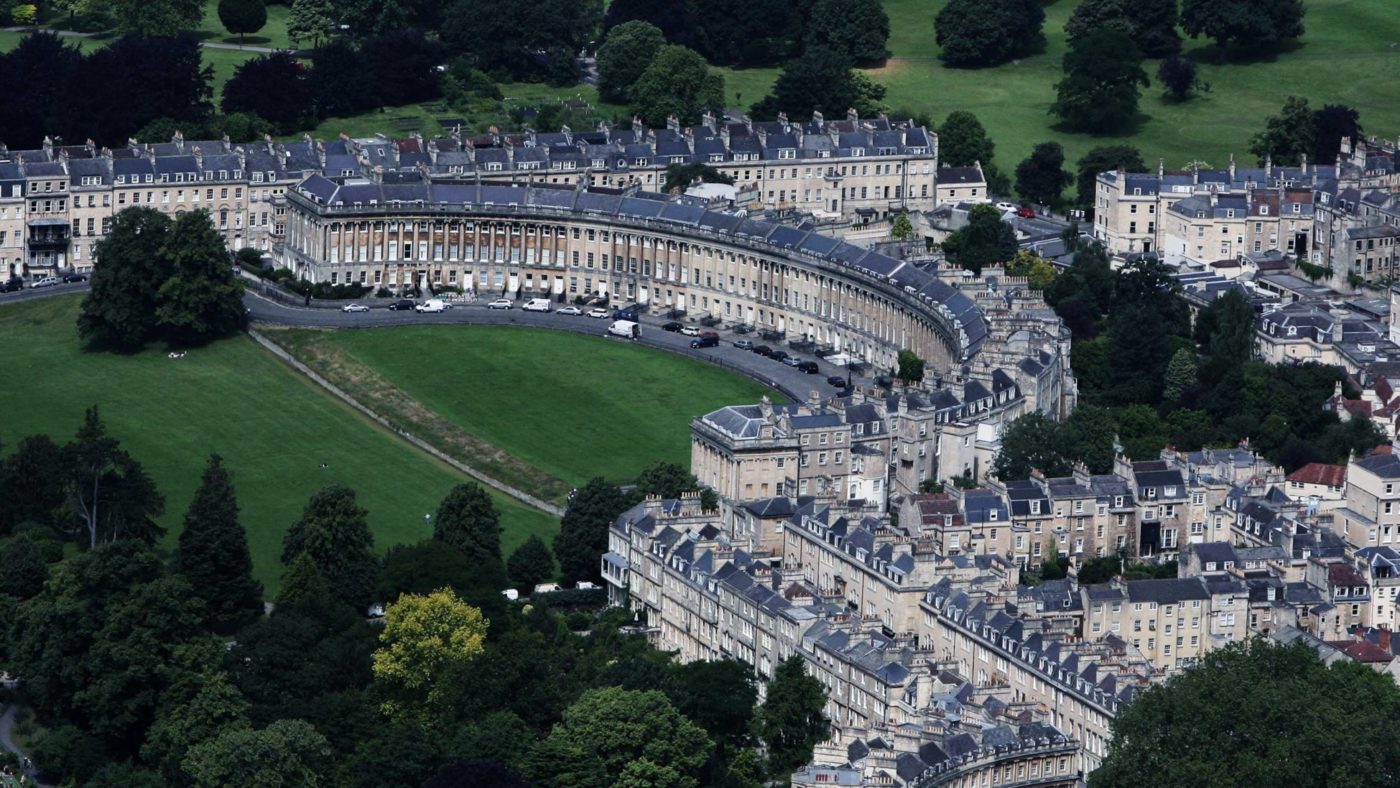

Because if the commonplace tells us that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, we are remarkably similar in when we behold it. No amount of PR will make a tourist visit Cumbernauld instead of Cambridge, or prefer Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh to the Taj Mahal. A fad passes: then human nature cannot see ugliness as anything else. Indeed, the best examples of this ‘revealed preference’ are modern architects themselves. After putting up the Lloyd’s of London building, Richard Rogers fled to a regency townhouse in Chelsea. The Lloyds building is already rotting; the townhouse is not.

Yet the very popularity of beauty (that people visit Bath, not Brum) renders architects afraid to attempt it, lest they become the worst thing of all, a populist. Cool to be Renzo Piano, naff to be the classicist constructor John Simpson.

The difference is starkest in the great twentieth century power-centres, already decaying, especially Brussels and its Rond–Point Schumann, the current centre of Europe itself.

Once a cluster of Flemish limestone townhouses, the Rond-Point is now the archetype of what one French anthropologist calls a ‘non-place’. In this knot of glass and steel, the last beautiful thing, the golden art deco Residence Palace is now engulfed by Europa, an immense steel pin-screen within a cube. But walk two-blocks from the roundabout and you will find a glorious old neighbourhood of orange tiles, copper rooftops and stone walls, and you know that you have crossed the boundary from non-place back to place. That is when you realise that the Rond–Point was designed to make us all forget that we are in a country with a past at all.

Buildings that could be anywhere on earth create a sense of normlessness, because they tell the people who use them that they could be anyone on earth. This feeling is strongest in the most post-national, thus most heavily policed, place we have – the modern airport. In Heathrow’s Terminal 5 all decoration has been ripped away to reveal only skeleton.

Art, said WH Auden, is our means of breaking bread with the dead. Globalist architecture is designed to prevent the communion. Instead, we experience the nausea of rootlessness, a state of anomie where no value is better than any other.

These can no longer be called socialist buildings, however. The generation that fantasised about building the revolution was replaced by one that dreams only of completing the Single Market. Stripped of identity, we are encouraged to venerate only profit, our buildings designed only for maximum light and worker productivity. Let the eye pass from St Paul’s Cathedral to Jean Nouvel’s hulking black shopping mall next door; observe that for public sculpture, Google has chosen at their St Giles office a clump of shapeless red blobs; note how our artistic elite topped the Fourth Plinth with an upturned thumb, grossly distended; this replaced a giant blue cock.

Welcome to London: we believe in nothing. But this faddishness keeps the mind in the tumult of here and now. Styles whose motifs have persisted expand our sense of time, granting, like the sea, a sense of perspective.

The same phenomenon is apparent across the world. Despite a building boom unprecedented in human history, modern China has created no new Venice, indeed no new Suzhou. Tourists everywhere now crush into the places built before the last century, vacationing being also a holiday for the eyes. But that tells us something. If we preserve it, beauty pays.

Beauty doesn’t create wealth just because people come to see it. Beautiful old things tell us we are responsible for the longer term, making us expect more virtue of ourselves. I would bet that there is more corporate malfeasance to be found in the blank glass towers of Canary Wharf than behind the neoclassical porticos of the old City, because buildings are statements of belief, and an angry monolith with no stylistic difference to an abattoir says ‘take the money and run’.

Freedom itself is also upheld by virtue, because it means less government intervention in our behaviour. We developed strict planning rules because we perceived that architects could no longer be trusted. Bringing back the virtue of beauty would render these unnecessary.

And there are signs of life. Following the tragedy of the Grenfell fire, Danny Kruger, Create Streets, London Yimby, Jack Airey and others are asking how we can create new Georgian squares, because when people are asked, that’s where they say they would actually like to live.

Meanwhile, technology is giving beauty a second chance. For the first time since the industrial revolution, artisanship may become cheap again, thanks to 3D printing. Because virtue begets virtue, more democracy can mean more beauty in our cities. Why not make architects put their plans for new housing and civic buildings to an online vote, letting communities choose from a shortlist of buildings? This democracy could have stopped the Wandsworth fangs for a simple reason: no one likes them.

If people expect a new block of flats to be an art deco delight, the promise of beauty will turn nimbys into yimbys. Britons have turned against new building for a little-mentioned but simple reason, that they correctly expect them to be ugly. But we need more building if we are to increase our productivity and create wealth. Not only is beauty good, it will also make us rich.

Conservatives especially know that things become old because they are good. Evolutionary progress requires mutations, but most, turning out to be useless, are weeded out: counter-intuitively. The building on your street most likely to be demolished is therefore the newest.

The passage of time is always silently working, and when young Prince George is eventually King, and we are Georgians again, the Georgian townhouse will still be with us. To look upon beauty is to look upon something at one with the soul of the world, as Roger Scruton calls it; the alternative is that which denies its existence. And that cannot last forever.

The growing conservative movement for beauty should now make direct demands, and challenge the political parties to put policies for beauty in their manifestos. Why is there no such thing as an art nouveau airport or a hanging-garden car park? Simply because we have learned not to demand beauty. The decline of beauty is the great lacuna of the modern age. Now is the time to restore it.