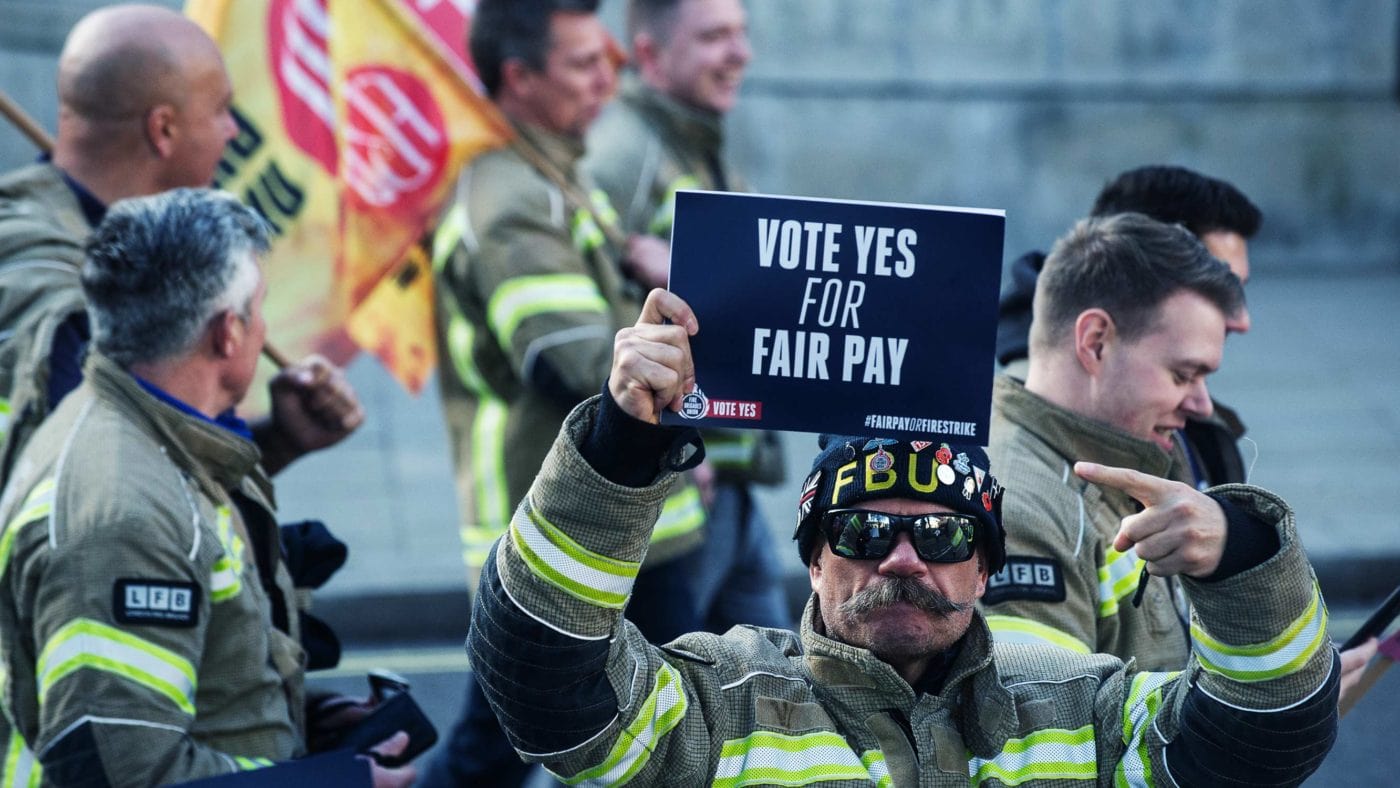

A quick look at the news confirms that Britain has been given the world’s worst advent calendar. Pick a date in December, and behind the door there’s an exciting new strike; will it be Royal Mail, teachers, bus drivers, railway staff, nurses, or ambulance workers today? Better hope you aren’t sick or travelling! And with more dates being announced, more unions joining in – fire brigades, Border Force, the Passport Office – we’ll soon manage a full month packed full of union fun for your inner communist. Even charity staff are walking out.

The proximate cause of the crisis is obvious; the war in Ukraine has led to massive disruption across European markets as the West and Russia cut economic ties. In turn prices – and energy prices in particular – have risen, driving up the cost of living, and driving down the value of workers’ pay packets. In turn, unions are doing what they do best, demanding higher pay for their workers, and using coordinated pressure to try and force employers into backing down.

Now take a step back, and take a look at the composition of these strikes. Does anything seem odd to you? At first glance, there’s a mix of public and private enterprises; Royal Mail is privatised, teachers are employed by the government, railway staff and bus drivers are private sector, nurses and ambulances public. And the data for strikes over the summer showed more private sector workers than public walking out.

At the same time, it is also pretty clear that the common factor is the British government. In some cases, it is the direct employer of those workers striking. In others, it has privatised or contracted out the provision of a service, and remains intimately involved in its regulation and pricing. It is notable that the general private sector – where workers are just as exposed to inflation as their public sector counterparts – does not seem to be experiencing a wave of unrest. Whatever is driving the winter’s discontent is to do with the Government specifically, rather than a general issue in the economy.

The first and most obvious possible answer is simply that the Government is a bad employer; wage growth in the public sector is currently lagging behind the private sector. It is certainly true that the Government is less responsive to market demands than private companies, but this has also manifested through public sector wages continuing to grow through the pandemic, even when payrolls elsewhere plummeted. This is a continuing pattern; even when the public sector pays less, its insulation from market conditions offers employment security in times of recession. The net effect is that the pay premium for working in the public sector has been eroded, down to rough parity. This doesn’t seem like enough to drive a mass walk-out though. If it were simply a matter of pay differentials, we would probably see more people leaving the public sector to take better pay offers elsewhere.

This in turn suggests that it’s something to do with how government and government-adjacent employers interact with workers. There is certainly something unusual going on; over 50% of public sector employees are union members, compared to a little under 13% of those in the private sector. One answer might be that the presence of the state as the single purchaser of labour in an industry creates circumstances under which unionised bargaining is more effective; the existence of a single large employer can drive down wages in the absence of competition; the lack of other employers removes the ‘safety valve’ of higher pay with the same technical skills; and the existence of one organisation to lobby against, rather than shop-by-shop recruitment of workers, makes it easier for unions to build consensus positions.

But there might be an even simpler explanation: the Government is in the habit of creating near monopolies, or privatising natural monopolies, and regulating them. It is also in the business of maximising the probability of re-election. Combine this with the existence of high salience periods in the calendar – sporting events, national holidays, and so on – and you create a recipe for piling pressure onto decision-makers: the breakdown of a critical national service in these periods is politically disastrous, and unions clearly believe the Government will eventually back down.

With no market pressure to keep costs down beyond the broad discipline of the bond market – and the Treasury’s dislike of spending – unions can push for higher pay rises than would be possible in the private sector. The fact that the wage premium for union membership in 2007 was twice as high in the public sector than in the private suggests that there is some validity to this argument.

If the strikes are the creation of government, they are also its responsibility. Refusing to engage in negotiations is not a credible stance; when the government is deeply entwined with an industry, pouring billions in subsidies into it and setting the boundaries within which negotiations occur. And it is also fully capable of placing restrictions upon the legality of strikes, and stripping legal protections from unions and workers in critical industries, as Joe Biden has done with US railway workers. That would be a much better Christmas gift to the country than a month of misery.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.