As a child, I attended Sunday School at St John’s Anglican Church. We were taught each week the best stories in the world. What is clear to me is that narratives are everything. And as black kid whose parents came to Britain in the 1950s, those Biblical stories have not only shaped my life, but may well give us a clue about the untold story of black success in Britain.

One of my favourite stories was the one about housebuilding, told by Jesus in the Book of Matthew:

‘Everyone then who hears these words of mine and does them will be like a wise man who built his house on the rock. And the rain fell, and the floods came, and the winds blew and beat on that house, but it did not fall, because it had been founded on the rock. And everyone who hears these words of mine and does not do them will be like a foolish man who built his house on the sand. And the rain fell, and the floods came, and the winds blew and beat against that house, and it fell, and great was the fall of it.’

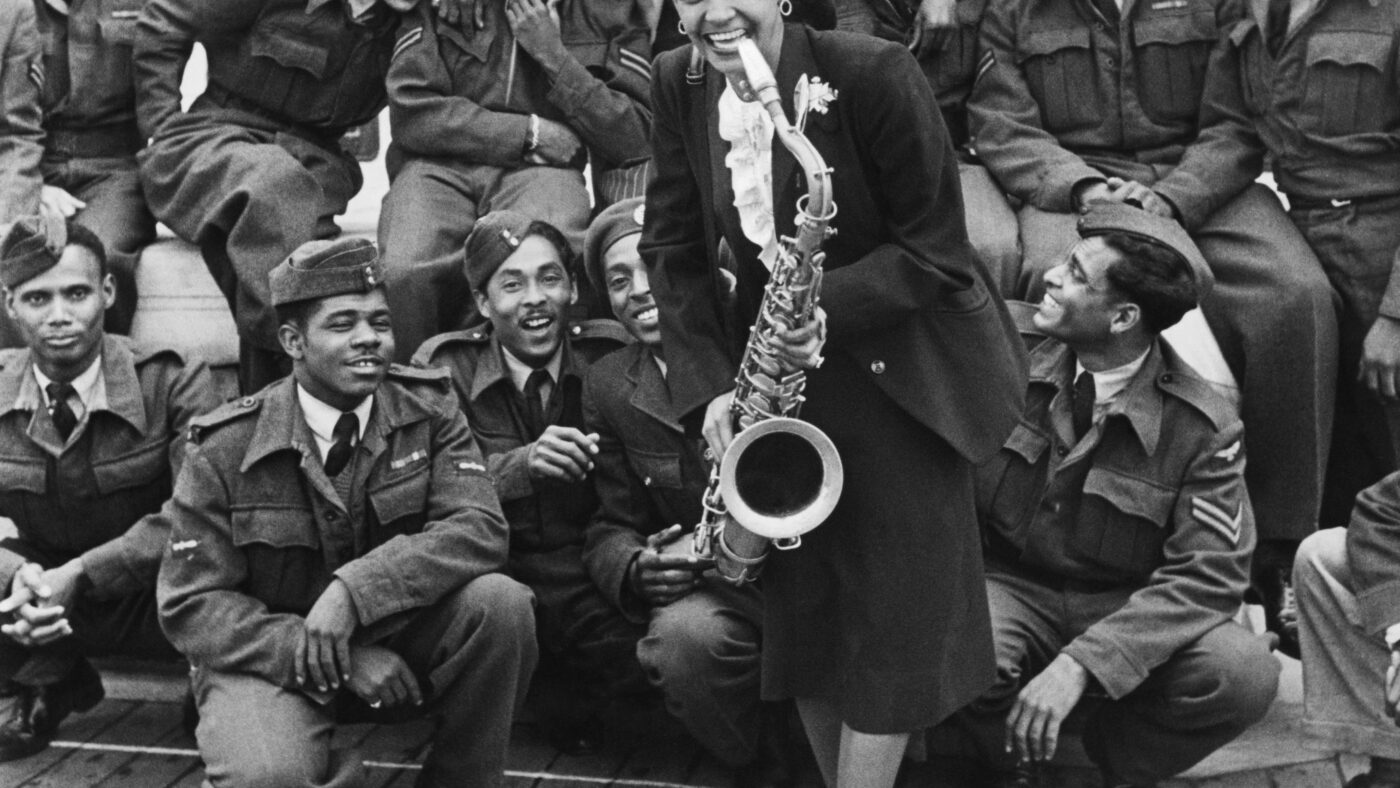

I love this story because it reminds me of the proper story of the so-called Windrush generation, now forever associated with the scandal instigated by Theresa May’s hostile environment strategy.

In 2012, May, who was Home Secretary at the time, introduced the Hostile Environment Policy, saying that: ‘The aim is to create, here in Britain, a really hostile environment for illegal immigrants.’ It was meant to be a display of power against illegal immigration, but it failed to see that a tiny minority of people from the Caribbean, who did not build their house on the rock but lived in Britain, would be harmed by this policy.

We now have a story of a people defined as victims of a hostile nation that not only treated its overseas citizens with hatred and contempt, but also tried to deport those who did not have their papers. The Windrush scandal has now buried itself into the collective conscience as a group of people who simply got ripped off by the British.

However, what about those like my mum, who built their house on the rock? In 1981, I remember vividly her showing me her beautiful brand new British passport. She was swearing under her breath at the fact that she had to pay money to move from an overseas dependent passport to a new British one. But that was her only complaint.

The data showed that most of those Caribbean migrants did build their house on the rock, and sorted out their immigration status in accordance with the new laws – though of course the injustice of that hostile environment policy can never be justified, and those who were victims deserve their full compensation.

However, what we are not doing when we talk about Windrush is linking it with what can be described as a spirit of agency and self-affirmation. The metaphor of building houses is so relevant for that generation. It was adversity that forced them into purchasing their own homes, well before the practice of buy to let. And they did so despite open hostility and racism, most infamously codified in the phrase ‘no blacks, no Irish, no dogs’.

They soon became the biggest occupational home owners in Britain, and some became landlords of multiple properties. Many of the apparently battered Windrush generation are technically millionaires, having assets in newly gentrified areas of London like Brixton and Balham. Some have cashed in that wealth and retired to huge mansions in the Caribbean. Yet no one wants to talk about their success. It’s as if this positive journey through the British landscape should be hidden, as the country replays the shame of the hostile environment.

I will always remember the day when the letter came to our house confirming that my family had totally paid off their mortgage. Then I checked in with other Caribbean families. Many of them had now become outright owners of their homes. This was a wonderful achievement of a generation, yet all we get is the misery of the Windrush scandal.

That generation were also models of how, in adversity, communities come together. They organised their own informal banking system because they couldn’t get loans, they were busy building homes in the Caribbean, ready for their retirement. And they seemed to have a party every week.

My Sunday school stories were never some work of spin or a distraction from the reality of racism. They fortified me, gave me the strength to believe in my own agency. They were the instruction manual that would prevent me collapsing when life became tough.

We need to give these to a generation feeling the storms of the madness of social media. Our schools, too, need to find those classical stories – and stop turning the Windrush generation into uber-victims.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.