The story of humanity over the course of the last two centuries is nothing short of remarkable. As late as 1870, life expectancy in Europe and the world was 36 and 30 years, respectively. Today, it is 81 and 72 years respectively. In 1820, 90 per cent of humanity lived in extreme poverty. Today, less than 10 per cent does. In 1800, 88 percent of the world’s population was illiterate. Today, 13 per cent of the world’s population is illiterate. In 1800, 43 per cent of children died before their fifth birthday. Today, less than 4 percent do. In 1816, 0.87 per cent of the world’s population lived in a democracy. In 2015, 56 per cent did.

In 1800, food supply per person per day in France, which was one of the most advanced countries in the world, was a mere 1,846 calories. In 2013, food supply per person per day in Africa, the world’s poorest continent, amounted to 2,624 calories. Slavery, which was rampant in most parts of the world in 1800, is now illegal in every country. Finally, for the first time since the start of industrialisation in mid-18th century, global inequality is declining as developing countries catch up with the developed world.

The long-term trends in human welfare are undeniable, but indicators of human well-being have continued to improve at a dizzying speed within the lifespans of the teenagers in the West, many of whom are either ignorant of the real state of humanity or dissatisfied with the speed of progress.

Opinion polls indicate that they have soured on free enterprise and are answering the siren calls of such socialists as Jaremy Corbyn in the United Kingdom and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the United States. The hearts of the young are in the right place, but that does not absolve them of knowing the facts. After all, if they want to change the world, they need to know something about it. To that end, I have looked at some of the most important indicators of human wellbeing, especially in the poor countries, since the start of the new millennium. The results are encouraging and ought to give us reasons for optimism.

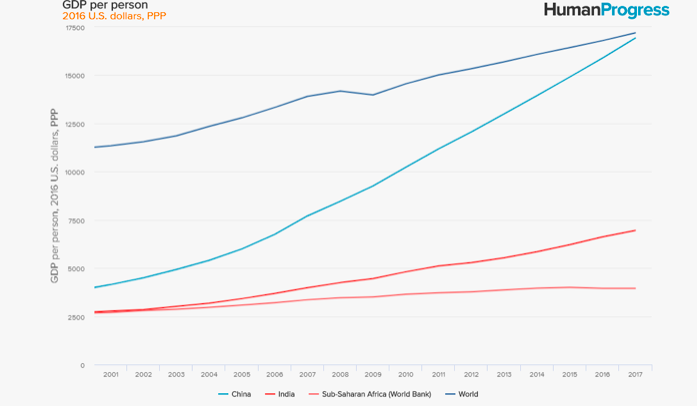

GDP per person, 2016 U.S. dollars, PPP, 2001-2017

Global: $11,347 to $17,196 (or 52 percent increase)

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA): $2,698 to $3,948 (or 46 percent increase)

India: $2,773 to $6,950 (or 78 percent increase)

China: $4,147 to $16,924 (or 308 percent increase)

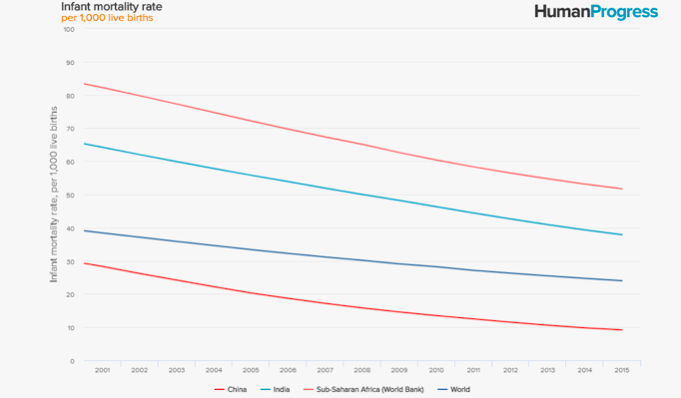

Infant mortality rate, per 1,000 live births, 2001-2015

Global: 38.4 to 23.9 (or 38 percent decline)

SSA: 82.2 to 51.7 (or 37 percent decline)

India: 64.2 to 37.9 (or 41 percent decline)

China: 28.3 to 9.2 (or 68 percent decline)

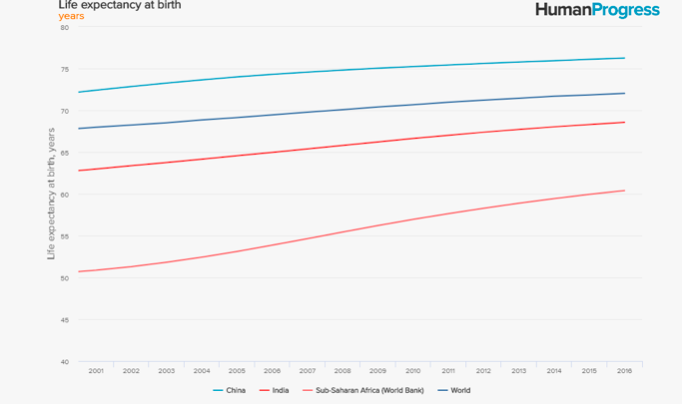

Life expectancy at birth, years, 2001-2016

Global: 67.9 to 72 (or 6 percent increase)

SSA: 50.9 to 60.4 (or 19 percent increase)

India: 62.9 to 68.6 (or 9 percent increase)

China: 72.4 to 76.3 (or 5 percent increase)

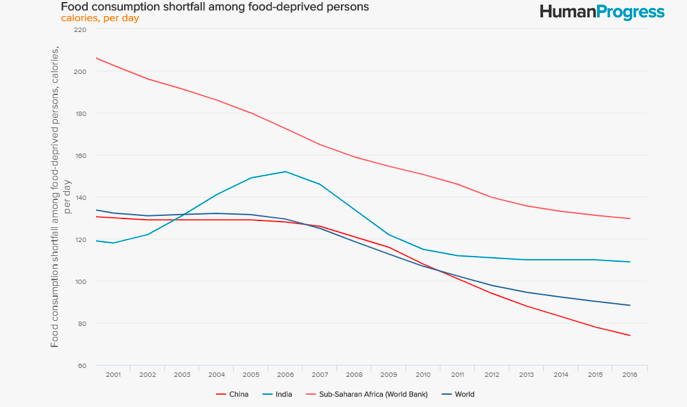

Food consumption shortfall among food-deprived persons, calories, per day, 2001-2016*

Global: 132.3 to 88.3 (or 33 percent decline)

SSA: 202.7 to 129.6 (or 39 percent decline)

India: 118 to 109 (or 8 percent decline)

China: 130 to 74 (or 43 percent decline)

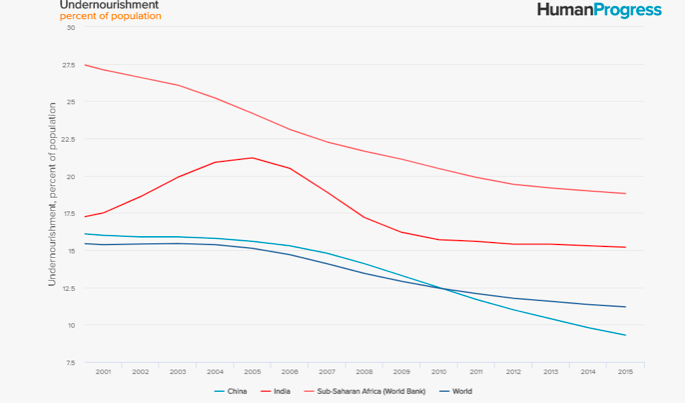

Undernourishment as a percentage of population, 2001-2015

Global: 15.4 to 11.2 (or 27 percent decline)

SSA: 27 to 18.8 (or 30 percent decline)

India: 17.5 to 15.2 (or 15 percent decline)

China: 16 to 9.3 (or 42 percent decline)

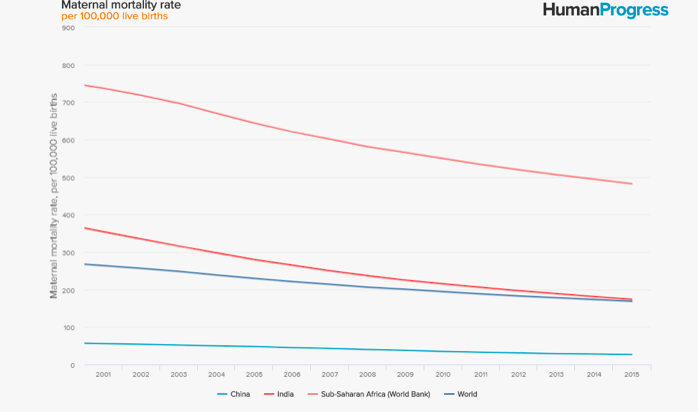

Maternal mortality rate, per 100,000 live births, 2001-2015

Global: 263.9 to 168.7 (or 36 percent decline)

SSA: 736.9 to 481.9 (or 35 percent decline)

India: 354 to 174 (or 59 percent decline)

China: 56 to 27 (or 52 percent decline)

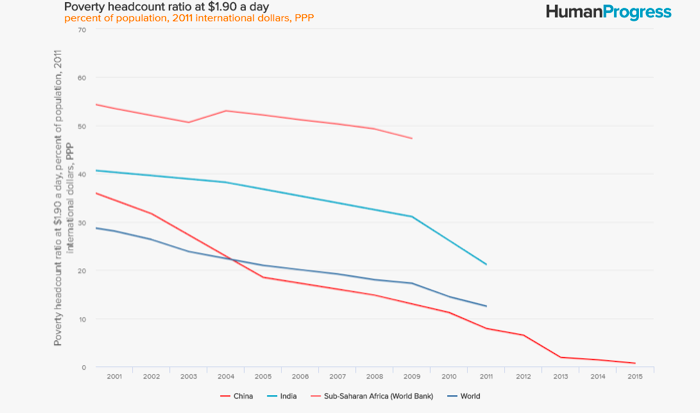

Poverty headcount ratio at $1.90 a day, adjusted for inflation and PPP, percent of population, 2001-2015

Global (2011): 28 to 12.5 (or 55 percent decline)

SSA (2009): 53.5 to 47.3 (or 12 percent decline)

India (2011): 40 to 21 (or 48 percent decline)

China (2015): 34.5 to 0.7 (or 98 percent decline)

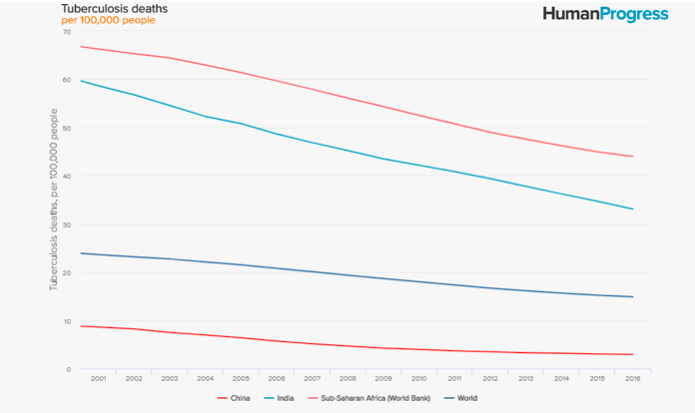

Tuberculosis deaths per 100,000 people, 2001-2016

Global: 23.6 to 15 (or 36 percent decline)

SSA: 66 to 44 (or 33 percent decline)

India: 58.6 to 33 (or 44 percent decline)

China: 8.6 to 2.9 (or 66 percent decline)

The world is not a perfect place and never will be. As long as there are people who go hungry or die from preventable diseases, there will always be room for improvement. Everyone has a role to play in helping those in need. Genuine help, however, should start with a clear understanding of what works and what does not.

Free societies characterised by the rule of law, property rights, domestic competition and free trade have a much better record of tackling human misery than their socialist alternatives. The young followers of Corbyn and Ocasio-Cortez should, therefore, keep the Hippocratic Oath in mind: If you want to help, first do no harm.

*The depth of the food deficit indicates how many calories would be needed to lift the undernourished from their status, everything else being constant. The average intensity of food deprivation of the undernourished, estimated as the difference between the average dietary energy requirement and the average dietary energy consumption of the undernourished population (food-deprived), is multiplied by the number of undernourished to provide an estimate of the total food deficit in the country, which is then normalized by the total population.

**These are total numbers, which do not take into account population growth.