This piece was originally published on the Centre for Policy Studies’ new monthly newsletter, which you can sign up to here.

Housing is a policy area that attracts a disproportionate number of bad takes. And most of them seem to end up being published in The Guardian.

Recently, the paper produced yet another article denying that Britain has a housing crisis. Any problems in the market, argued the Marxist lawyer Nick Bano, have nothing to do with a lack of housebuilding, and everything to do with those evil landlords.

Bano promptly got an absolute kicking from Paul Johnson of the IFS, Torsten Bell of the Resolution Foundation, and of course me. But it’s worth going through some of the arguments he put forward – not just because far too many people keep making them, but because the answers tell us some surprising and very useful things about how we could actually end the housing crisis.

The article starts by pointing out that ‘there has not just been a constant surplus of homes per household, but the ratio has been modestly growing’.

This is a favourite Nimby argument. But it’s also completely meaningless. Households only form when there are homes for them to move into. So by definition, there can never be more households than homes. And the size of the gap between them just tells you that some of them are second homes, or empty properties, or bought by foreign buyers.

In our CPS paper ‘The Case for Housebuilding’, we went into the houses and households issue in great detail. We pointed out that high house prices had discouraged household formation – to the tune of an estimated half a million households in London alone.

But an even simpler way to debunk this nonsense is to look at the number of young people stuck living with their parents – which has increased hugely. These are households which haven’t formed, because there aren’t enough houses. On the latest statistics, 27% of those aged 20 to 34 – that’s 3.6m people – are still living with their parents, up from 2.4m (or 20%) back in 2000. That’s your missing households right there.

Talking about households also gets us into another point. The nature of our housing needs is changing. People today are both richer – as Ant Breach of the Centre for Cities explains here – and more likely to want to live alone, especially when they’re around retirement age. All other things being equal, that means we need more houses even if the population remains the same size. Which of course it isn’t, thanks to unprecedented levels of legal migration – a topic on which the CPS has had much to say.

There was a lot more nonsense in the piece, all of which you can find debunked in my original thread. (Including the point that rental households tend to cram in more people than owner-occupied ones, so abolishing landlordism would in fact make housing pressures worse…)

But it did at least remind me of a very significant point – one which I suspect almost nobody reading this will be aware of.

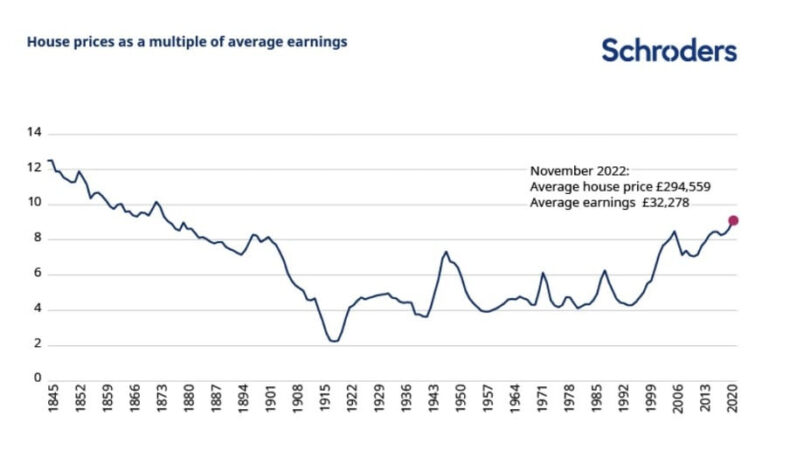

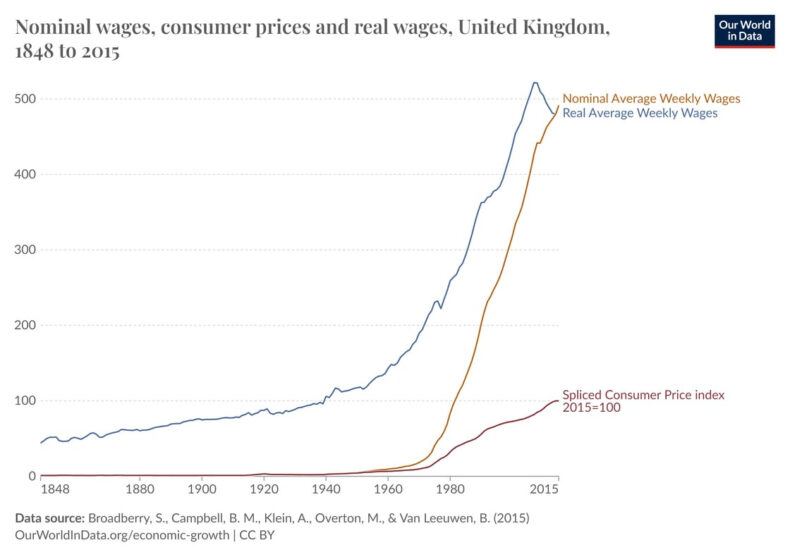

One of the most remarkable phenomena of the Victorian age was a collapse in the cost of housing. Between 1845 and 1915 house prices fell sixfold relative to earnings.

Part of this fall came about because earnings increased. But they didn’t actually go up by that much. So what caused housing to suddenly become far, far more affordable?

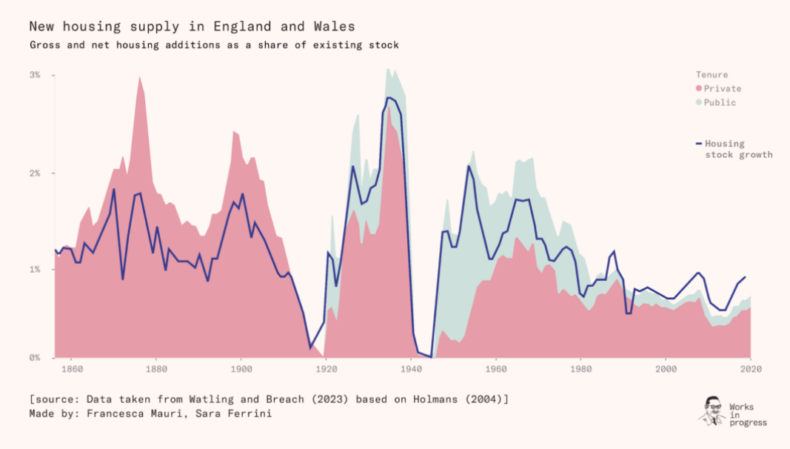

The obvious answer is that we built an absolute shedload of houses. Which are today known as Birmingham, Liverpool, London etc. It wasn’t until after 1945, when the state asserted national control of the land supply, that affordability went into reverse.

But there’s more to this story. As our friends at Works in Progress have pointed out, these homes were overwhelmingly delivered by private housebuilders.

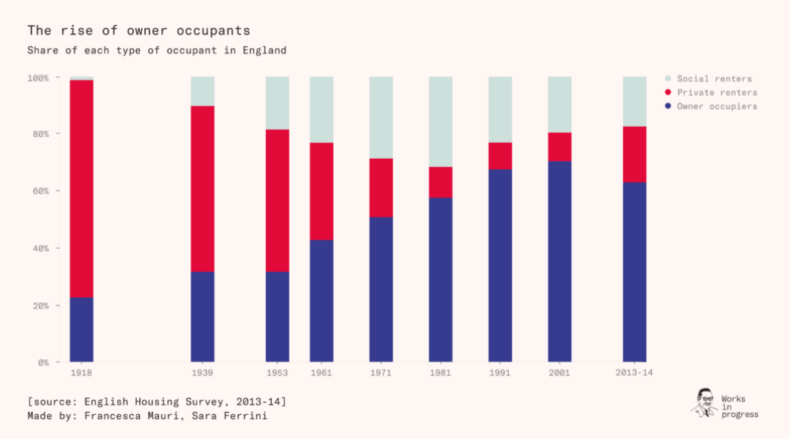

And they were overwhelmingly built not for sale, but for rent.

To go back to that Guardian article, it’s hard to argue that landlords are the cause of the housing crisis when the sharpest falls in housing affordability this country has ever seen were accompanied by a massive boom in private renting.

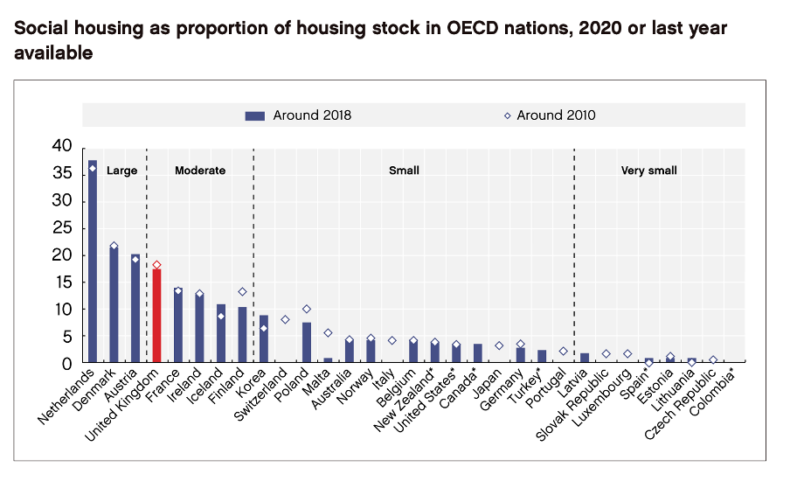

It also shows helps disprove the common argument on the left that the way to solve the housing crisis is just to build social housing. There’s nothing wrong with building social housing – indeed, it’s what we should have used the receipts from Right to Buy for. But Britain still has the fourth largest stock of social housing in the OECD, as a proportion of our overall housing stock. The core problem is that that stock is not big enough – which is why we need more market housing as a matter of urgency. (Also, the Government really doesn’t have the money to build millions of council houses.)

In other words, in trying to prove that capitalism and housebuilding are at the root of all evil, the Guardian not only utterly failed to make its case, but provided a welcome reminder that what really matters is actually building some houses – and that the golden age of UK housebuilding came when we let the market take the wheel.

Indeed, it’s often said that the private sector simply can’t build all the homes we require. I’d reply that it’s amazing what might happen if the state actually let it try.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.