In recent decades, China’s suicide rate has declined more rapidly than any other country’s. It has fallen from among the world’s highest rates in the 1990s, to among the lowest — below the US and only slightly higher than the UK.

Rural women are responsible for the lion’s share of the decline. Unlike in most countries, Chinese women have a higher suicide rate than Chinese men do and in rural areas women may be two to five times more likely to kill themselves than in cities.

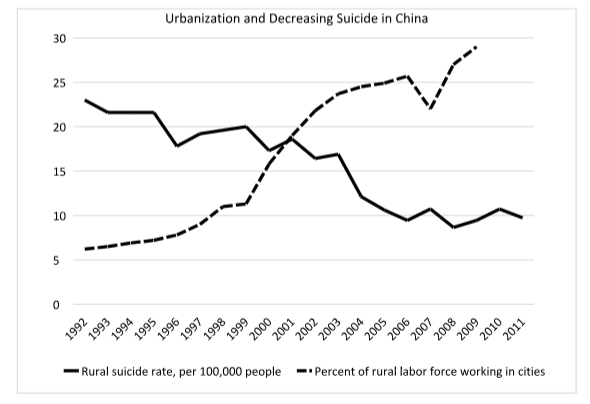

What changed? In short, globalisation and labour market opportunities. The Economist published a graph showing how the dramatic decline in suicide coincided with more Chinese leaving rural areas to seek urban employment. They used data from Tsinghua University. I have updated the graph with more recent data below.

As more Chinese have left farms in the countryside to work in factory cities, the suicide rate has plummeted. This may be shocking to many people in rich countries. That is because many people who enjoy post-industrial prosperity worry about “sweatshop” conditions and exploitation in factories. They may also have an idealised opinion of rural peasant life, while a dark view of factory life popularised by Karl Marx is still surprisingly popular.

Marx thought that factory work was worse than farming because workers would be alienated from the product of their labour and exploited. Philosophy professor Nancy Holmstrom of Rutgers University shares his outlook. “The lives of subsistence peasants may be limited, but materially adequate and stable,” she claims. She believes that factory work has made workers worse off.

The fact that rural Chinese commit suicide at higher rates than urban Chinese would suggest otherwise. So would the fact of China’s dramatic decline in suicide as more and more rural Chinese choose to work in cities.

In reality, factory work is typically an improvement compared to poverty in the countryside. Factory conditions can be harsh and no one is claiming they should not improve. But far worse back-breaking labour and grinding poverty often define rural existence. The option of migrating to a city to take up factory work can be a lifeline to those contemplating suicide. Leaving behind rural farms for urban factory work typically translates into higher wages and a better standard of living.

It also can mean freedom from the more restrictive social norms of the countryside – particularly for women. Women “are more likely to value migration for its life-changing possibilities” than men, since gender roles are less limiting in cities than in the traditional countryside. That’s according to former Wall Street Journal reporter Leslie Chang in her book Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China.

The World Health Organisation also attributes the decline in suicide partly to women gaining the option to leave the countryside to work in factory cities. That typically improves their social and economic conditions. “More and more [women] become migrant workers or make money on their own,” Dr. Su Zhonghua of Jining Medical School told the WHO. He also pointed out that even women in homemaking roles are now less confined as a result of changing social norms.

Similarly, The Telegraph‘s Yuan Ren ascribes the high rural suicide rate to harsh gender roles in the countryside: “Even today, many rural women are treated like second class citizens by their own family, subordinate to their fathers, brothers and – once married – their husband and mother-in-law.” A 2010 study found that whereas marriage has a “protective” effect against suicide in many countries, marriage may increase suicide risk among young rural Chinese women.

The author noted that “being married in rural Chinese culture usually… further limits [a woman’s] freedom” as a possible explanation for this. Escape from such gender roles helps explain why many women choose to migrate. Initially, Chinese society viewed factory work as shameful to a woman’s reputation and dangerous. Despite the social stigma, many women pursued factory work anyway and over time, migration to cities has become practically a rite of passage for rural Chinese.

Today, urban life affords factory workers – but particularly women – the promise of opportunity, economic mobility and freedom. As The Economist put it, “Moving to the cities to work… has been the salvation of many rural young women, liberating them.” Globalisation has, quite literally, saved many of their lives.