In last week’s Spring Statement, Chancellor Philip Hammond announced that the government would “undertake a review of the international evidence on the employment and productivity effects of minimum wage rates” led by Professor Arin Dube of the University of Massachusetts.

There is nothing inherently wrong with an evidential review. What is concerning, however, is who the government has appointed. Dube is among the minority of economists who think that minimum wage hikes do not decrease employment. There is no way that Dube will be able to look at the evidence, part of which he has written, in a neutral manner.

The government could have chosen someone with an open mind, or a panel containing experts with various perspectives. They could have included Professor David Neumark, who has spent decades studying the minimum wage. Dube himself has admitted that “In terms of sheer volume, David Neumark is probably the most prolific economist to have written on the topic” of the minimum wage.

Professor Neumark told the Adam Smith Institute’s Adam Smith Lecture last year that two-thirds of all studies, and 85 per cent of reliable studies, show a negative impact of the minimum wage on employment. The job and hours losses are felt most prominently by lower-skilled, younger and minority workers.

Understanding the impact of the minimum wage

You don’t need to be a professional economist to understand that increasing the minimum wage will have an impact on employment. A simple thought experiment will do the trick.

The Low Pay Commission, before the introduction of the National Living Wage in 2015, typically only recommended small increases in the minimum wage that, in its view, businesses could handle. However, imagine if the Low Pay Commission recommended £1,000 per hour minimum wage. Do you have any doubt that it would lead to mass unemployment? There is clearly a point where the minimum wage starts to bite.

Nevertheless, there is evidence that smaller minimum wage increases have not increased unemployment in the short run. Businesses do not tend to lay off staff immediately in response to a minimum wage hike. This can give a false impression that the minimum wage is not having an impact.

Jonathan Meer and Jeremy West have shown the employment impact of minimum wage increases is actually felt in the long-run. This is because the minimum wage cuts off the opportunity to get a job by pricing people out of the market. If your labour adds £6 an hour to a business, but the minimum wage is £7, you will not get employed. Just because you want people’s labour to be worth more doesn’t override economic fact.

The other often underappreciated impact is businesses reducing hours and the disproportionately negative impact on low-skilled, young, and minority workers—the first on the chopping block.

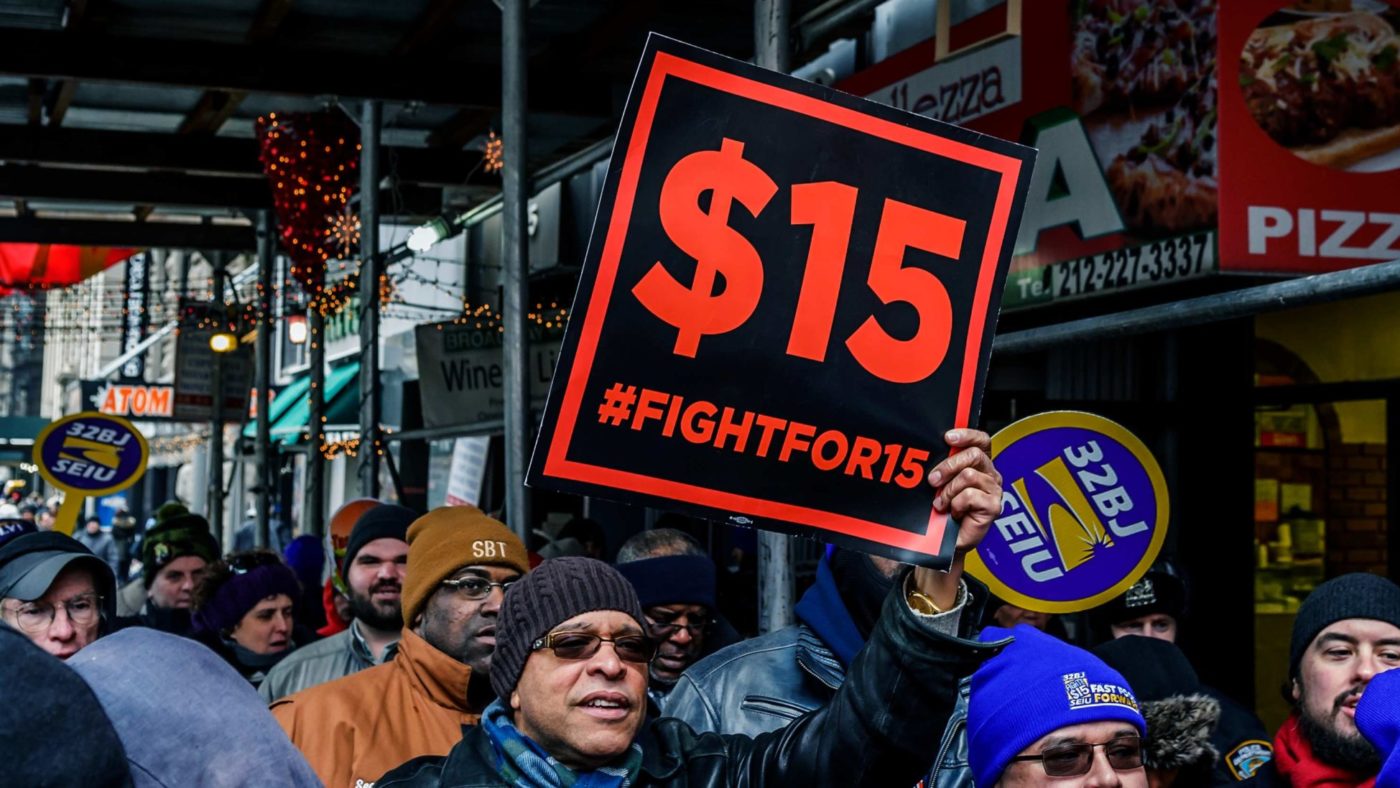

The Seattle experience has provided plentiful new data on the impact of the minimum wage. In 2014, the city’s council announced their intention to raise the city’s minimum wage incrementally to $15 an hour. The researchers appointed by the city to analyse the impact concluded that the increase from $11 and $13 had not quite worked as intended. They found that one-third of businesses in Seattle cut workers and hours and two-thirds responded by increasing prices. While wages are 3 per cent higher, the actual hours worked in low-wage jobs has declined by around 9 per cent. This means low wage workers are an average of $125 per month worse off thanks to the minimum wage hike.

There is also evidence to suggest the impacts of the minimum wage are most severe for the ‘just about managing’ businesses. Dara Lee Luca and Michael Luca of Harvard Business School found that restaurants with worse Yelp reviews were more likely to shut in response to a minimum wage hike. Looking at the case of San Francisco, they found a “one dollar increase in the minimum wage leads to a 14 percent increase in the likelihood of exit for a 3.5-star restaurant.” They also found that 5 star rated restaurants were not impacted by the minimum wage increase.

The dignity deficit

Proponents of the minimum wage usually do not care much about the evidence. They put the case in moral terms; they claim that those who oppose the minimum wage increases hate the poor.

The minimum wage isn’t just about pounds and pence, it’s about lost opportunity and meaning.

Arthur Brooks, the outgoing president of the American Enterprise Institute, has argued that America doesn’t have an inequality problem as much as a dignity problem. The same applies in Britain. It may be difficult for many to survive on welfare, but the social safety net ensures almost everyone has access to a roof over their head and food on their kitchen table. Being in poverty today in Britain does not often mean starving on the streets.

What many people don’t have, however, is dignity in their lives. They feel disconnected from a political class that doesn’t understand them. They don’t have a job in which they are needed, and have the regular social connection and something to do during the day. Work is purpose, belonging, meaning. It gives us a reason to get out of bed in the morning. It provides the opportunity for people to benefit from their own success.

There are 1.5 million Brits out of work, 2.4 million who are underemployed, and millions more who have given up on looking for a job altogether. Raising the minimum wage does nothing for those people – in fact it makes it harder to climb onto the skills ladder by cutting off the bottom rungs. If people can’t build skills, most obviously, the skill that comes from experience which makes you more valuable to an employer, they cannot demand a higher wage in future. They’re stuck on the indignity that comes with welfare and regular visits to the local Job Centre.

How to tackle poverty

We all have the same goal: helping the poor. It’s therefore important to understand why people are poor.

The most common reason that people are in poverty is that they do not work.

A household containing an unemployed individual is twenty times more likely to have a low income than a household where everyone is in full time work. Child poverty follows the same pattern. Half of children in a workless family live in poverty, compared to 15 per cent of families where one person works.

Minimum wage hikes do nothing for these people – in fact, increasing the minimum wage is the path to pushing even more people out of work, creating more poverty, and encouraging businesses to automate.

The minimum wage isn’t a well-targeted way to help the poor. Most minimum wage earners are not in low income households – they are second wage earners and teenagers with part-time jobs. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has concluded that “the benefit from minimum wage increases is concentrated among middle-income households, not the lowest-income households”. The IFS found that about two-thirds of the benefit of minimum wage increases go to households with average or higher earnings.

Minimum wage hikes also push up the cost of goods that lower income earners are more likely to purchase, such as fast food. This makes the minimum wage a particularly bizarre and inadequate redistributive tool. It isn’t taking from the rich and giving to the poor, it’s just taking from the poor to give to slightly less poor. It’s less Robin Hood, more hoodwink.

The good news is that we have worked out how to increase household incomes by taking from those with higher incomes and giving it to low income households: a redistributive welfare system.

The central challenge is to design a welfare system that increases household incomes without discouraging work. The Working Tax Credit, which is now combined into Universal Credit, encourages people to work and reduces poverty. It’s the proven method to get people out of poverty. It also clearly shows the cost of helping the poor, rather than hiding it by outsourcing social goals to businesses.

An alternative model, recently proposed by David Neumark, is for the government to partially subsidise minimum wage increases. Neumark’s ‘Higher Wages Tax Credit’ would ask taxpayers to pay for half of the difference between the prior minimum wage and the new minimum wage for each hour employed. The credit would phase out at wages higher than the minimum wage.

There are much smarter solutions to poverty than minimum wage hikes, sadly, however, it would appear the government’s latest review is set up to ignore these options.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.