Last month’s announcement of the latest price cap level was good news for consumers everywhere – because energy prices are continuing their downward trajectory. From the staggeringly high levels of the Energy Price Guarantee which ended last summer (£2,500, itself heavily subsidised), we’ll be down to an average annual dual fuel bill of £1,690 from April, £238 lower than current levels.

But in a little-noticed move, on the same day the Government also slipped out a call for evidence on the future of default energy tariffs. While it was predictably buried under the avalanche of price cap coverage, the potential implications are arguably far more profound.

In essence, electric vehicle (EV) drivers in future could be defaulted onto an energy tariff which punishes them for charging up at peak times and rewards them for charging off-peak.

To understand why, let’s start with today’s energy market. Most domestic consumers pay a flat rate per unit of energy they consume (i.e. regardless of the time of day), in addition to a daily standing charge.

But that’s not actually how the underlying wholesale markets work – there, the price of electricity changes every half hour and varies substantially throughout the day (and the year). Prices respond to the basic forces of supply and demand, and are generally highest between 4 and 7pm (when everyone is getting home from work), and lowest in the middle of the night (when everyone is asleep).

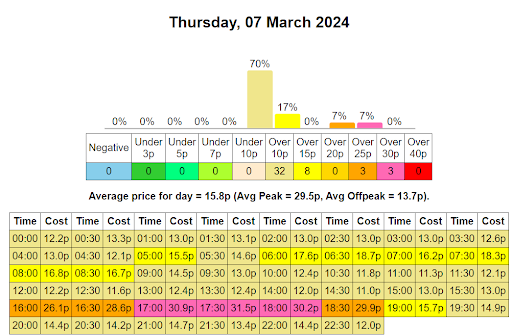

As a visual representation of this, have a look at today’s pricing from the Octopus Agile tariff. The price at 5.30pm is 32p, nearly triple the price at 4.30am (12p).

Half-hourly pricing in action

To account for this reality, some people with old-style storage heaters have ‘Economy 7’ or ‘Economy 10’ tariffs (often with a special meter), where the price of electricity is cheaper overnight, either for seven or 10 hours. This is known as a ‘static’ time of use tariff, where consumers face only a ‘peak’ and an ‘off-peak’ rate. These static time of use tariffs, which have been around since the 1980s, are simpler than ‘dynamic’ time of use ones, where the rate changes throughout the day and varies day-to-day. Yet such dynamic pricing is becoming increasingly common in other countries, and Octopus has introduced it here with their Agile tariff.

But the big shake-up in this world is Net Zero. All of those heat pumps and EVs will substantially increase our demand for electricity, particularly in a domestic context. (Indeed part of the reason the concerns about charge points in the press are overblown is that the vast majority of charging will happen at home, or potentially in your workplace car park).

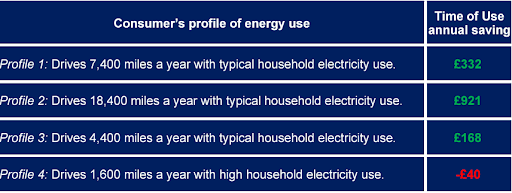

So naturally, many energy suppliers are beginning to offer EV charging tariffs which allow people to take advantage of cheap electricity overnight. While you’ll need a smart meter to take advantage of these, if you have an EV you can save substantially from switching to such a ‘Time of Use’ tariff, as the Government pointed out in its consultation (below). Even better, ‘smart’ cars and EV charge-points increasingly tie in with your energy supplier, obviating the need to remember to start charging the car at a certain time (OVO for example offers such a tariff today).

Potential savings from EV owners switching to a Time of Use tariff

But things start to get a bit stickier as take-up increases. If everyone in the year 2035 is driving their shiny new EV home from work, and decides to power up at 6pm, this will increase demand for electricity substantially. Basic economics will tell you that this will in turn drive up the price of electricity (in the wholesale market). And of course if this sort of behaviour becomes the norm, then tariffs will have to rise to reflect this change in supply and demand. Without time-of-use tariffs, this could mean everyone – including those without EVs – paying for those higher prices.

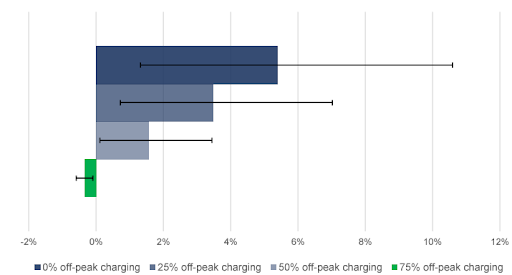

There’s a well-illustrated example of this in the Government’s consultation. If 75% of drivers charge in the middle of the night, then those on a standard tariff would see cheaper bills in 2030 – but if nobody does, prices could be as much as 10% higher. This is a pretty remarkable statistic – and all the more remarkable because these price rises would not just apply to EV drivers, but to everybody. So in effect, those without a car (or with a legacy petrol or diesel vehicle) would be subsidising the charging behaviour of their EV-driving counterparts.

Change in flat rate tariffs from increased EV ownership in 2030

So we now get to the crux of the issue. In the future, if you own an EV, should your ‘default’ tariff be smart, at least to some degree? The Government seems to be heading in that direction. (Although for now this is only a call for evidence at the tail end of the parliament, and of course a future Government could decide otherwise.)

To be absolutely clear: you the consumer would continue to be able to choose whatever tariff you want, smart or not-smart. Such ‘default’ tariffs only kick in when a customer hasn’t actively chosen a tariff, for example when a cheap fixed deal expires and they don’t choose a new one.

But this matters because at least today, such default tariffs are depressingly common – consumer ‘disengagement’ with the energy markets is at an all time high. (Of course much of the blame for this lies with Ofgem’s price cap itself, as the CPS has previously pointed out).

If this policy goes ahead, many EV drivers could face higher bills if they make a habit of charging their car during peak hours. It’s worth reflecting what a profound shift this would be. Most people today simply plug in their devices without thinking about it, so this would be quite the shake-up. Navigating the politics of such a change could be tricky (it’s unlikely to be a coincidence that this consultation was slipped out on the same day as the price cap announcement).

Alternatively, this could be much ado about nothing. Many EV drivers today have proactively chosen EV tariffs given the savings involved, and it’s plausible that this trend continues as take-up increases. If so, the backstop of today’s ‘default’ tariffs may become a relic of the past, with EV drivers happily on ‘evergreen’ charging tariffs. Or perhaps as the market develops, commercial incentives alone will drive suppliers to ensure their customers are on smart tariffs, without the need for regulatory intervention.

But the Government isn’t banking on this, and seems keen on an insurance policy to get ‘disengaged’ households to charge off-peak. Yet there are a host of questions to be answered about how this would work in practice.

The consultation explicitly mentions that ‘households should not be forced into complex tariffs they are not prepared for’ – how to balance that sentiment with this approach? One can imagine the default tariff being ‘static’ (eg only peak and off-peak prices) rather than a dynamic one, but even so, when exactly would be ‘peak’? All day or just 4-7pm?

And would this only apply for customers with EVs, or also those with electric heating such as heat pumps, heat batteries, storage heaters and so on? Or those with an EV, but who more often charge at work rather than at home? What about poorer customers who may simply be unable to afford an increase in their bills – would there be any sort of allowance or differentiated treatment for them?

All that said, it’s important not to lose sight of the fact that there is a substantial prize ahead of us. A more innovative, flexible and competitive retail market could unlock new solutions and substantial savings for consumers. But while getting EV drivers on to time of use tariffs is undoubtedly the right goal, this consultation throws up a whole host of questions about how exactly to get there.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.