After a long period of virtual silence on railway matters, the Labour Party has announced a plan for the future of this near-two-century-old industry. Or at least shadow transport secretary Louise Haigh has announced that the plan will be set out ‘in two to three weeks’ time’.

For the moment, the headline is that passenger travel will be renationalised ‘with no compensation’. That sounds like red meat for the Party’s Left, but really amounts to the square root of nothing at all. Following the collapse of the 1990s franchising model during Covid, the Train Operating Companies (TOCs) are on short-term contracts simply to run the trains to Department for Transport specifications. When those contracts expire (and all bar the Elizabeth Line contract end during the next Parliament), presumably the lines will be operated by a government-owned ‘operator of last resort’ as is currently the case for seven of the 16 former franchises.

This was exactly what was proposed under Jeremy Corbyn’s regime. It skates over many issues which we will hope to see at least considered when the details of Ms Haigh’s proposals emerge. While allowing the contracts just to run out naturally will save money compared with buying them out, it means we can expect two or three years with contractors having zero incentive to improve their service or maintain decently the stations they operate – let alone entice more passengers back on trains.

To pretend that full-scale renationalisation will be costless ignores the fact that the TOCs do not own the 15,000 passenger vehicles in use on our railways. Between 80 and 90% of these are owned by ten or so Rolling Stock Operating Companies (ROSCOs), which lease them to the TOCs. The RMT union wants to bring rolling stock back into public ownership as well, arguing that, like Gordon Brown’s Private Finance Initiative, this model raises costs in the long run. They may be right, but the ROSCOs have brought a huge amount of private funding into the industry and enabled new generations of trains which the government would probably not have funded under the old British Rail set-up. To buy out the ROSCOs could cost upward of £50bn, so it ain’t going to happen. More plausibly, if Labour decides that in future the nationalised entity will buy its own trains, we can expect fewer replacements and the life of clapped-out old vehicles being extended for longer.

There is so far no mention of the freight sector, a purely private operation which has recovered well from the Covid period and from the virtual disappearance of its previously lucrative coal trains to power stations. Freight has considerable potential for increased markets as we attempt to move to green transport options. But, particularly now HS2 has been stripped back, track capacity in crucial parts of the country needs to be increased to enable freight to expand. A nationalised business focused on passenger transport may neglect freight.

Nor do we know what will happen to Open Access train operators – fully private companies such as Grand Central, Lumo and Hull Trains. While overall passenger numbers are still way below pre-Covid levels, the Open Access companies’ numbers are now actually above where they were before the pandemic. Unlike the TOCs operating under current government contracts, these companies have a genuine incentive to grow the market – as indeed did companies such as Virgin when the franchise model was in its pomp. There are plans for some further entries into the market on neglected routes. But in future Open Access businesses, if not actually forbidden from the network under Labour’s plans, may find it more difficult to obtain reasonable timetable slots.

Is a Labour government prepared to continue shovelling money into the railways at the current rate? Subsidies are nearly double what they were pre-Covid, and in the last financial year easily exceeded the amount raised in fares. Revenue from passengers is, in real terms, only about three-quarters what it was in 2019.

Privatisation led to a huge increase in passenger numbers, a remarkable achievement for an old industry which had seemed in permanent decline. But changes in travel habits since lockdown, with a collapse of commuting and a big drop in business travel, mean that the task of recovery requires a flexibility and entrepreneurial drive which few government-owned businesses have demonstrated in the past. Labour needs to spell out just how their plans will ensure that this happens.

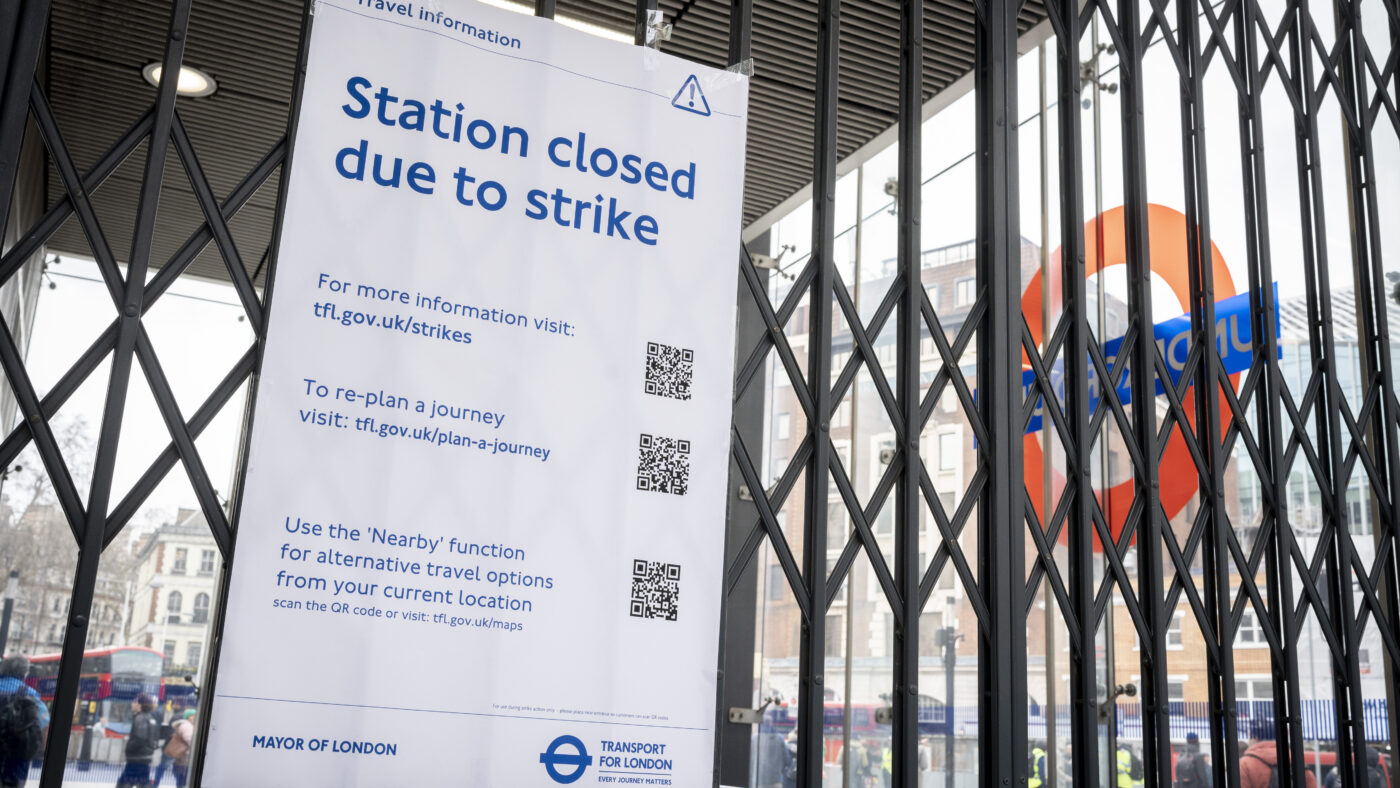

A large part of the task will be changing working patterns on the railways. We need changes in rostering to cater for expanded weekend services, changes in the function of ticket offices if they are retained, scrapping of unnecessary guards on trains, new forms of track monitoring and maintenance. The unions bitterly oppose such changes, but they are essential to productivity improvements and containing costs. And we must end the continued recourse to strikes which punish the general public and inhibit attempts to get people back onto trains.

So a fundamental issue will be how to deal with the unions. Industrial action on the railways has a long history; the first recorded rail strike was in 1842, the first national strike in 1911, and unions have been traditionally militant ever since. The Conservatives have failed to crack this: their long-promised Minimum Service Levels legislation is being ignored as too difficult to use, a result predicted here over a year ago.

Can Labour do better? The danger is that full renationalisation will increase union leverage. Whatever Louise Haigh and her team have dreamed up, it must tackle this problem rather than come out with a load of guff about the wonders of a socially-owned railway.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.