For an hour or more on Tuesday morning, browsing the web became a deeply disconcerting experience. If you tried to look at the BBC website, you got an error message, and likewise for The Guardian or The Financial Times sites.

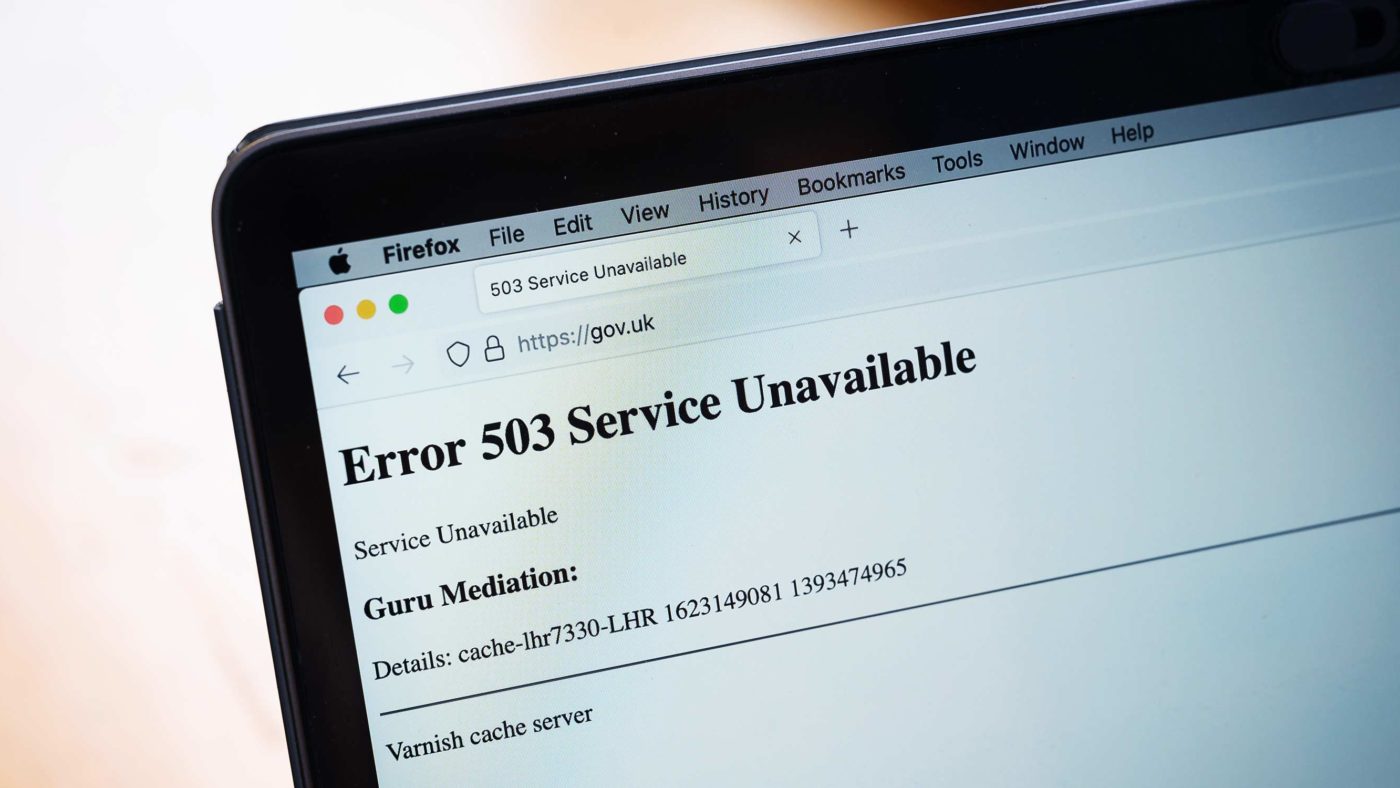

It wasn’t confined to the UK, either – The New York Times, CNN, and dozens of other major websites were all similarly unavailable. If a panicked user had worried this was some signal of impending nuclear war or similar and tried to go to the Government for information, they’d have been disappointed – gov.uk was offline too.

What’s perhaps more unsettling is that none of this was the result of some nefarious actor or natural disaster – incidents like the 2006 Boxing Day tsunami can sever undersea internet cables, causing major outages – but the result of someone changing some settings at a company almost no one has heard of.

That company is fastly, a business that generally works behind the scenes to make the internet faster and, perhaps ironically, more reliable. Traditionally, someone would host their site on a server in one location – perhaps on the east coast of the USA. Whenever anyone in the world wanted to access the site, the traffic would flow across continents between the two computers.

Services like fastly avoid that by making lots of local copies of their customers’ websites, so that a user in the UK accesses the site from the UK, a German user accesses it within their own country, and so on. When it all works, it makes the internet faster, much more reliable and reduces international traffic. But when it goes down, as we saw on Tuesday, it takes a lot of other sites with it.

It wasn’t some kind of sophisticated cyberattack that took down fastly, either. Instead, according to the company’s account of events, someone updated some configuration settings on one of its systems – the kind of routine work engineers at these companies do daily.

But this time it did something unexpected, causing something of a chain reaction that eventually took much of the web offline for more than an hour. The effect was compounded because some services that themselves power websites use fastly to operate – meaning that even sites that have never been fastly customers ended up being affected.

If this makes the modern internet sound alarmingly like a house of cards built on shaky foundations, that’s because it is. Lots of services that keep the network operating behind the scenes have long chains of dependencies – one service might draw on code from another site, that in turn relies on open source code libraries that may or may not have been kept updates for decades.

If someone updates a modern web browser, or operating system, or something else, they always run the risk of suddenly making it incompatible with one of the more dated components in this often inscrutable web of scripts, tools, and services.

Outages like that caused this week by fastly are becoming an increasingly common online phenomenon – one notorious incident was caused when a Pakistani internet provider tried to block one YouTube video within the country, but instead blocked the site for hours to almost half the world.

Last year almost every site operated by Google was taken offline after a fastly-type error. Each serves as a warning that the internet has become critical infrastructure – but has none of the protections given to most other infrastructure.

The reality is the internet is held together with little more than spit, glue and hope. The protocols on which it runs were designed decades ago for a small network largely used by academic institutions and the occasional hobbyist. Efforts to rebuild or refashion those protocols for the modern era tend to move painfully slowly, a task we could roughly liken to trying to rebuild a spaceship while it’s actually travelling through the galaxy, with the added complication of needing every person onboard to approve every individual change.

It is no surprise then, that progress is slow – and so people looking to offer good, reliable web services look to services like fastly instead, re-centralising the internet and creating a few major points of failure.

And the stakes are far higher than the occasional hour or so with minimal internet access. There are so many vulnerabilities in the architecture of the internet that a malicious actor looking to exploit them would have no shortage of targets.

A country wanting to launch a military operation against a neighbour could, for example, launch massive cyberattacks to take out much of the internet and cause a large-scale distraction. Others might take down the internet for fun, or for profit.

The web going offline for an hour here or there is not, on its own, the biggest problem we have in the world this year. But we should be taking it as a warning that there are major problems that need fixing before they lead to disaster. The risk is that we’ll keep ignoring these, too.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.