Is democracy in trouble? Asked about the state of democracy around the world during a recent interview, former US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright replied, “I am worried about the fact that there are conditions out there that provide the petri dish for something terrible to happen, where some of the definitions I gave of fascism would take hold.”

In some places, such as Russia and Venezuela, democracy is already dead. In other countries, including Turkey and the Philippines, representative government seems to be on its last legs. Even in America, many believe, democracy is under threat. “Democracy Dies in Darkness,” warned the Washington Post after Donald Trump’s election as U.S. President. “Fascism’s coming to America,” Bill Maher opined on his popular HBO show last week.

The data, however, tell a different story. While the number of countries that can be characterised as democracies fell from an all-time high of 121 in 2016 to 120 in 2017, the quality of democracy continues to improve in countries that have remained democratic. On that measure, the world is more democratic than it has ever been.

Writing in 1989, an American academic reflected on the gradual implosion of communist dictatorships and growing democratisation around the world in an essay entitled The End of

History?. “What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of post-war history,” Francis Fukuyama wrote, “but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalisation of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”

Since he penned those words, Fukuyama has come in for a great deal of criticism . Today, he himself seems to be having second thoughts. “Twenty five years ago, I didn’t have a sense or a

theory about how democracies can go backward,” Fukuyama said in a 2017 interview. “And I think they clearly can.” True enough, populism of both the left-wing and right-wing varieties is

on the rise in many parts of the world. Yet, it would be a mistake to dismiss Fukuyama’s original thesis altogether.

From a historical perspective, democracy is a relatively new phenomenon. For most of humanity’s recorded history, people have lived under some form of autocracy. Power was concentrated in the hands of one person, such as an absolute monarch, or a small group of people, such as oligarchs. Even ancient “democracies,” such as Athens and republican Rome, denied the vote to women and slaves.

Modern democracy or, to be more precise, the representative form of government, arose in Western Europe and North America during the 18th century. It then slowly spread to other parts of the world, reaching a high point in the early 1920s. The rise of fascism, Nazism and communism between the world wars reversed some of the democratic gains. To make matters worse, many of the countries that gained independence after World War II fell into the hands of autocrats. By the early 1970s, roughly twice as many countries could have been described as autocratic as democratic.

All that changed with the collapse of communism. The Center for Systemic Peace (CSP), a research institution in Virginia, USA, evaluates the level of democracy in each country on a scale from -10, which denotes a tyranny like North Korea, and 10, which denotes a politically free society like the United Kingdom. Most countries fall somewhere in between those two extremes. In 2017, for example, the United States scored 8 and France 9.

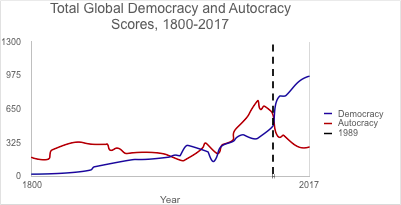

According to the CSP’s research, the combined score of the world’s autocracies fell from 571 to 282 between 1989 and 2017. The combined score of the world’s democracies rose from 494 to

967. Similarly, the number of countries with positive scores rose from 58 to 120, while the number of countries with negative scores declined from 82 to 43. The picture is equally encouraging, once democracy scores are adjusted by population size.

In 1989, less than half of humanity lived under some form of democracy. By 2017, two thirds of people on Earth enjoyed the benefits of some form of representative government.

None of the above denies the dangers of excessive populism. But the fortunes of democracy should be kept in a proper perspective.

In terms of the number of countries that qualify as more-or-less democratic, the world had reached its peak in 2016. The quality of democracy, however, has risen steadily and has never been higher. All in all, it would be premature to write democracy’s obituary just yet.