One of the most exciting economic debates of our time puts face to face the economists who forecast a “long stagnation” and those who advocate the start of a huge wave of innovation brought by the NBIC technologies (Nanotechnologies, Biotechnologies, Information and Cognition).

For the “long stagnation” believers, the last big wave of innovation began in the first industrial revolution at the end of the 18th century (especially the steam machine). It gave birth to the transport revolution of the 19th century, followed by the “belle epoque” innovations like motors cars and electricity, and at lastly the “30 glorieuses” innovations like washing machines. The first industrial revolution led to happy consequences like the soaring of individual revenues, the meltdown of extreme poverty and the rise in life expectancy. But now, these sad economists say, big innovations are over. For sure we hear of NBIC but, like internet 20 years ago, the impact of these innovations cannot be seen in the productivity figures. In this regard they are right. Recent figures of productivity, including the post 2008 crisis period, are despairingly low, the most spectacular example being the United Kingdom. This is a central point when thinking about our economic future, as productivity constitutes the main driver for economic growth in the long term. Without strong productivity, it is indeed long stagnation which will arise, with its nasty offspring: high public debt and mass unemployment.

In contrast, according to optimistic economists, NBIC technologies are about to increase productivity and potential growth. If the data are not able to grasp this happy change, this is because we are at the very start of the move. The diffusion of innovation always follows an exponential curve. The utilization rate of the new product, say 3D printing or self-driving car, accelerates regularly. After a few years, consumption explodes. This is exactly what we saw with cars at the beginning of the 20th century, or with television in the 1950s. We just have to wait. Optimist economists also fairly argue than the official productivity indexes are not up-to-date anymore especially because they are very quantitative. But they fail to assess precisely the quality of the production due for instance to incorporation of nanotechnologies in chemical products. In most OECD countries, the national account systems were set up after the Second World War when NBIC were just science fiction.

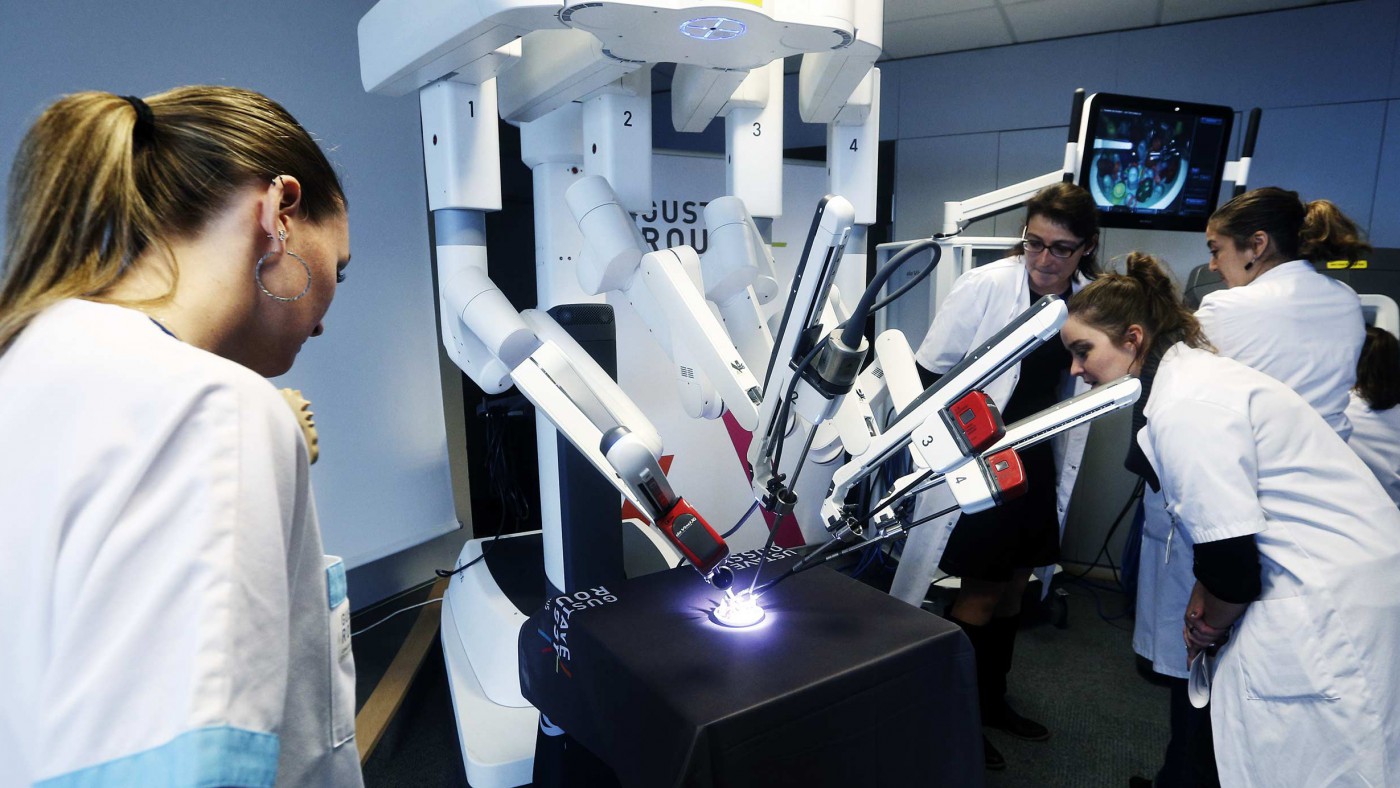

Optimistic economists are right but their diagnostic is incomplete. A deepened review of recent economic research shows that the main mistake of the “long stagnation” advocates lies elsewhere. The Israeli-American economist Elhanan Helpman proved from the end of the 1990s that a radical innovation could not only have no impact on productivity, at least at the short term, but also trigger a recession. To understand this paradox, take the real life example of surgery robots in hospitals. In theory these robots drive huge productivity gains: less invasive and more precise surgeries, less post-surgery complications, outpatient hospitalization. Only good news. Yet nearly all hospital managers who bought a robot assert that they are not able to make their expensive investment profitable.

There are a couple of explanations for Helpman’s models. On one hand, most of radical innovations are not completely refined when put on the market. To be perfectly usable, an innovation needs a tracking of the first utilizations and a tuning. That is why the productivity of the first institutions which use it can be deceptive. On the other hand the advent of a radical innovation like a robot outmodes brutally older technologies. Physical capital obsolescence rockets and the human capital (including the surgeons’ one) is devaluated. But the replacement of old technologies and old know how is a lasting and costly process. In the transition period, productivity and growth melt down. Firms have to gather money, change machines and educate employees which requires large financing means, an efficient educational system et job market flexibility. The process is transitory but the transition is inevitable, painful and may last several years. To accept it, you have to accept that the better is to come. Maybe not tomorrow but the day after.