“PM tries to regain grip as death toll rises to 35” – cried an alarming Times headline back in March last year. Looking back now, more than 90,000 deaths later, it’s hard not to resort to gallows humour.

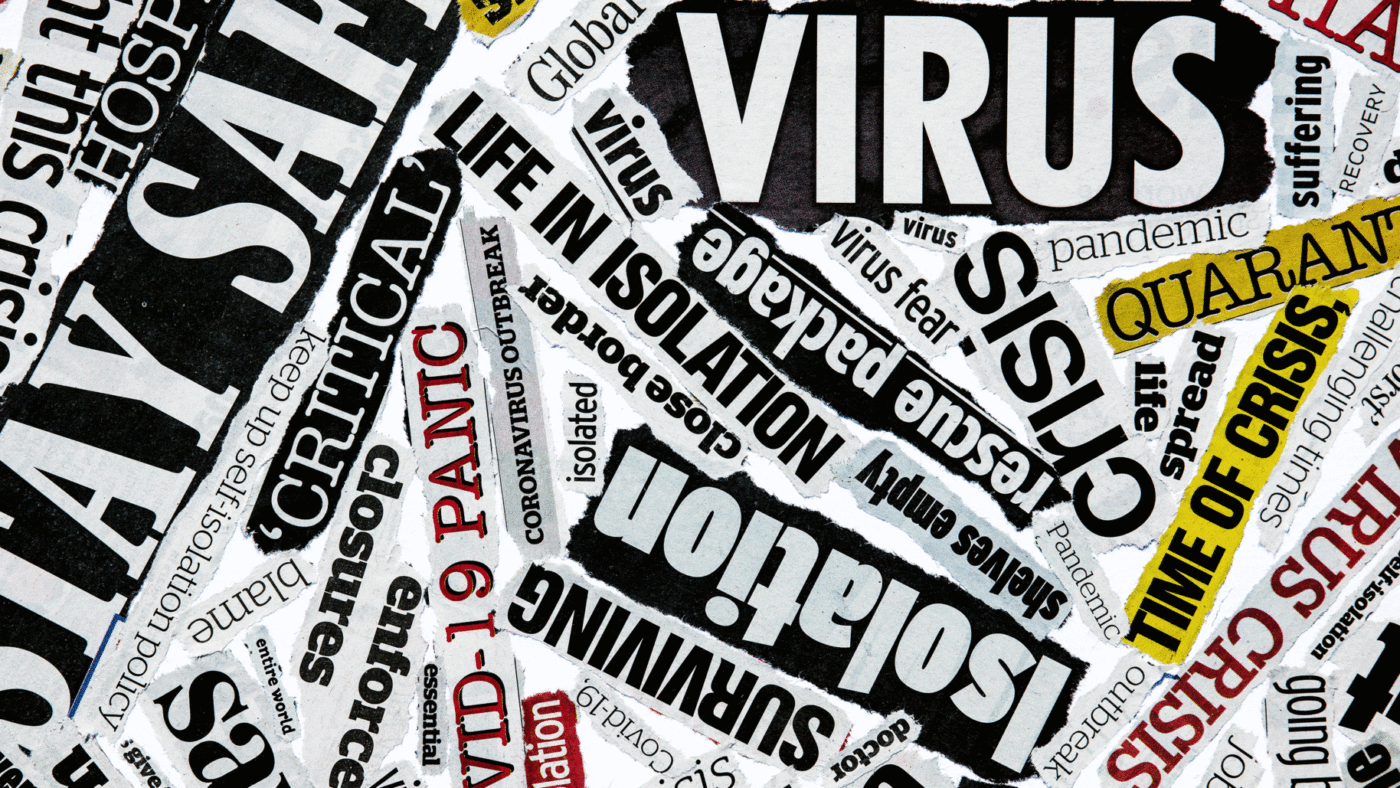

Sensationalism has never been far from the surface in the media’s coverage of the pandemic, even breaking through into respectable broadsheet newspapers. Whether through lack of competence, lack of time, commercial need for eye-catching headlines or political motives, journalists have ignored complexity and presented an overly simplistic, and therefore misleading, narrative.

I am not sure that there should really be a place for a journalist like Piers Morgan on a flagship TV programme regulated by Ofcom, but his approach has been typical of much of the tabloid coverage, with tweets such as “Failed on PPE. Failed on Testing. Failed on Care Homes. Failed on airport checks. Failed with ‘herd immunity’ strategy. Failed to stop mass gatherings. Failed to lockdown in time. RESULT: 62k dead & rising.”

Many thousands of words have been written about the UK’s high Covid mortality figures, usually based on the unchallenged assumption that our lockdown occurred too late. Very few articles have covered other relevant factors, such as our open economy, the presence of major transport hubs, our population density and demography and obesity levels. Indeed the media has sometimes bent over backwards to present the worst possible comparative picture.

The most ludicrous example is when Newsnight claimed in June that the UK had a higher daily level of COVID deaths than the entire rest of the EU put together. The only trouble was that they had failed to check the way in which data was compiled in other countries making the basis of the claim entirely specious, as compiled in a similar way UK deaths would have been massively lower.

Irresponsible or undercooked journalism doesn’t give readers a balanced view of what’s happening. It erodes trust in government which, at times like this, matters. It can induce unnecessary panic, making bad situations even worse, and it creates a poor environment for calm and logical decision making by ministers and civil servants.

There is surely a correlation between the dubious decisions made in the procurement of PPE and the doom laden headlines about shortages last spring. From the endless, uncritical coverage of Marcus Rashford’s food poverty campaign, you’d think perpetuating the emergency increase in universal credit was a no-brainer. But as Robert Colville has written “If, before this all started, you’d got together a load of welfare experts and said ‘you can permanently increase welfare spending by £6 billion or so, where’s it going to go’ I would have been very surprised if ‘raise the basic rate of UC and extend free school meals’ had won”.

Testing is another case in point. I honestly can’t remember the number of ‘long reads’ published over the summer lauding the German testing approach and identifying this as a key factor in Germany’s relative success during the first wave. Even then, a piece of me was screaming ‘but what about asymptomatic cases? How will testing prevent spread caused by those?’ Britain’s Test and Trace system has cost £22 billion to date, and been described by scientists as having had only a marginal effect. Maybe it is far-fetched to suggest the media had an effect on the decision to devote huge resources to this area, but it certainly feels like this was a pretty dubious choice. The fact is nothing, but nothing, is ever simple, and pretending that there are binary choices and easy trade-offs promotes poor governance.

A different and more immediate kind of damage has been done by the ‘gotcha’ stories about public figures who’ve broken the rules or, in the opinion of journalists, come close to doing so. There are, for sure, many examples which were clear cut and deserved exposure. There are other examples which were more nuanced and should have been covered with more balance. I would argue that Dominic Cummings’ travels are such an example. As a parent, it is hard not to sympathise with concerns over how to care for a young child with the prospect of both parents being seriously incapacitated. As a decent human being, it’s hard not to have some sympathy for a husband and father worried about his family home being under siege by the media (Indeed I am not sure there are that many countries in which such a senior figure could be left quite so exposed). I am not saying what he did was fully justified, merely that it was not as black and white as reported.

Many commentators, with what feels like glee, have reported on the dramatic effect that the Cummings’ incident had on public compliance with the rules – but perhaps the effect would have been less profound if responsible reporting had reflected the shades of grey. Rather clearer is the recent coverage of Boris Johnson’s bike trip. Seven miles is not much of a work-out for serious bike riders, and the Prime Minister clearly took exercise which started and ended at his front door. Was it really responsible, given the possible impact on compliance and therefore hospitalisations and deaths, to report this as a skirting of the rules? As John Ashmore has written on this site, “constant stories about the minority who do seem to be bending the rules encourages a perception that doing the right thing is a mug’s game.”

An element of the media approach to the pandemic has been political. Some journalists on flagship papers find it hard to be anything other than critical of the government. The cultural divide, exemplified and exacerbated by Brexit, has played a role in unbalancing more serious news coverage and analysis. However, commercial considerations, driven by the rise of non-traditional news channels, have probably played a bigger role in driving the traditional media to be more sensationalist. We should also not forget that lack of resources and financial pressure may have made it easier to ‘go with the flow’ on stories rather than devoting the time and effort to more detailed investigation.

No one wants to go back to the days of deference, when major scandals were quietly ignored. But the toxic distrust we now have between politicians and the media is also hugely damaging – it’s hardly surprising that they are two of the professions least trusted by the public. There must be a middle way, that acknowledges complexities and difficulties involved in decision making, and seeks to inform rather than agitate.

While the media has been happy to criticise every aspect of the Government’s handling of the pandemic – even though, in many cases, it’s really too early to judge – there is a distinct reluctance to acknowledge its own culpability, or the decreasing quality and increasing crudity of its output. I would like to see any post-pandemic public inquiry consider whether the media acted responsibly in its coverage. Sunlight may be just the disinfectant we need to clean up after Covid.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.